"ALLIANCE!"

MARXIST-LENINIST

Issue 52 April 2003

"DOWN WITH THE IMPERIALIST

WAR IN IRAQ!"

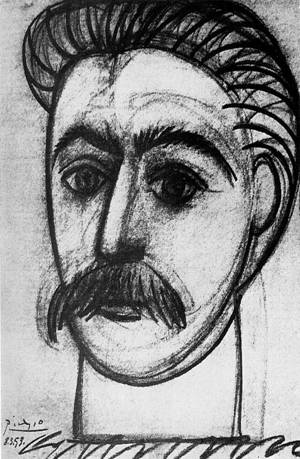

The Problem of Pablo Picasso

(1881-1973).

CONTENTS:

Introduction

Pablo Picasso – Early Years

Developing Cubism

Guernica – The Bombing

Guernica – The Painting

Impact of Picasso and Guernica on Russian Discussions Upon Socialist

Realist Art

Post Second World War - ‘Becoming a communist, Picasso hoped to come

out of exile'.

Conclusion

Bibliography

Introduction

Picasso poses a problem for the supporters of Marxist-Leninist

view of socialist art.

What ideology - both subjectively and objectively - did he represent?

What are the advocates of realism in the arts to make of Picasso's love

of gross anatomical distortions? How do most people react to his, perhaps

most famous work - "Guernica" - and what does it signify?And finally, what

was his relation to the Communist Party?

We contend that Picasso’s story is one of a gifted

artist, who was situated at a major turning point in history, between the

time of the “pure, isolated individual” and a time that history was rushing

forwards because of the consolidated action of masses. At this time, artists

(like everybody else) were confronted with a choice. Many took the wrong

turn – towards an isolationism, towards a “renunciation of reality”. One

art historian explains this as the end of approximately 400 years of art

history that had been till then, steadily moving towards a goal of more

and better ‘reality’. In its place was substituted a “form of existence

surpassing and incompatible with reality”, an existence that is “ugly”:

"The great reactionary movement of the century takes effect in the

realm of art as a rejection of impressionism change which, in some respects,

forms a deeper incision in the history of art than all the changes of style

since the Renaissance, leaving the artistic tradition of naturalism fundamentally

unaffected. It is true that there had always been a swinging to and fro

between formalism and anti-formalism, but the function of art being true

to life and faithful to nature bad never been questioned in principle since

the Middle Ages. In this respect impressionism was the climax and the end

of a development which had lasted more than four hundred years. Post-impressionist

art is the first to renounce all illusion of reality on principle and to

express its outlook on life by the deliberate deformation of natural objects.

Cubism, constructivism, futurism, expressionism, dadaism, and surrealism

turn away with equal determination from nature-bound and reality-affirming

impressionism.

But impressionism itself prepares the ground for

this development in so far as it does not aspire to an integrating description

of reality, to a confrontation of the subject with the objective world

as a whole, but marks rather the beginning of that process which has been

called the "annexation" of reality by art (Andre Malraux:

Psychologie de l’art). Post-impressionist art can no longer be called

in any sense a reproduction of nature; its relationship to nature is one

of violation. We can speak at most of a kind of magic naturalism, of the

production of objects which exist alongside reality, but do not wish to

take its place. Confronted with the works of Braque, Chagall, Rouault,

Picasso, Henri Rousseau, Salvador Dali, we always feel that, for all

their differences, we are in a second world, a super-world which, however

many features of ordinary reality it may still display, represents a form

of existence surpassing and incompatible with this reality. Modern art

is, however, anti-impressionistic in yet another respect: it is a fundamentally

"ugly" art, forgoing the euphony, the fascinating forms, tones and colours,

of impressionism."

Hauser, Arnold. "The Social history of Art" – Volume 4: 'Naturalism,

Impressionism, The Film Age'"; New York; nd; p. 229-230.

We will argue that Picasso took the 'wrong turn" - rejecting

realism - only to partially correct himself under the influence of a political

realisation of the horrors of war and capitalism.

Picasso forsook his earlier brilliance in works of

a realistic nature, to ‘invent’ Cubism. Both Cubism, and other related

art movements such as Surrealism, and Dadaism – were pained

attempts to come to terms with a rapidly changing society in the midst

or the wake of the catastrophes of the First World War. It was the expression

of an intense "hopelessness" of man’s possibility of changing anything

– for example, averting the First World War. It was also explicitly anti-rational:

"It arose from a mood of disillusionment engendered by the First World

War, to which some artists reacted with irony, cynicism, and nihilisim....

the name (French for 'hobby-horse') was chosen by inserting a penknife

at random in the pages of a dictionary, thus symbolizing the anti-rational

stance of the movement. Those involved in it emphasised the illogical and

the absurd, and exaggerated the role of chance in artistic creation......

its techniques involving accident and chance were of great importance to

the Surrealists and ... later Abstract Expressionists";

I. Chilvers, H. Osborne, D. Farr. "Oxford Dictionary of Art"; Oxford;

1977; p.147.

In the 1918 Berlin Dada Manifesto for instance,

life is characterised as where:

"Life appears a simultaneous muddle of noises, colours, and spiritual

rhythms, which is taken unmodified, with all the sensational screams and

fevers of its reckless everyday psyche and with all its brutal reality".

Cork, Richard "A Bitter Truth – Avant Garde Art & The Great War;

London 1994; p.257.

Dadaism involved a "nihilism" [""total rejection

of current religious beliefs or morals.. A form of scepticism, involving

the denial of all existence," "Shorter Oxford English Dictionary" Volume

2; Oxford 1973; ; p.1404.]. The nihilism of these movements "not only questions

the value of art but of the whole human situation. For, as it is stated

in another of its manifestos, "measured by the standard of eternity, all

human action is futile":

"The historical importance of dadaism and surrealism (lies)…. in the

fact that they draw attention to the blind alley …. at the end of the symbolist

movement, to the sterility of a literary convention which no longer had

any connection with real life .... Mallarme and the symbolists

thought that every idea that occurred to them was the expression of their

innermost nature; it was a mystical belief in the "magic of the word" which

made them poets. The dadaists and the surrealists now doubt whether anything

objective, external, formal, rationally organized is capable of expressing

man at all, but they also doubt the value of such expression. It is really

"inadmissible" - they think, that a man should leave a trace behind him.

(Andre Breton: Les Pas perdus, 1924). Dadaism, therefore,

replaces the nihilism of aesthetic culture by a new nihilism, which not

only questions the value of art but of the whole human situation. For,

as it is stated in one of its manifestos, "measured by the standard of

eternity, all human action is futile." (Tristn Tzara: Sept

manifestes dada, 1920)."

Hauser, Arnold. "The Social history of Art" – Volume 4: 'Naturalism,

Impressionism, The Film Age'"; New York; nd; p.232-233.

Paradoxically, contrasting to the Dadaists, at least

in some ways, Picasso exalted the individual. One can also see in him the

epitome of the bourgeois view of an artist as someone obsessed by not only

"art", but of acting the part of "an artiste" - so that their life story

is in itself a ‘work of art’. So Picasso said of artists that what was

important was "who they are, not what they did":

“It is not what the artist does that counts, but what he is. Cezanne

would never have interested me a bit if he had lived and thought like Jacquestmile

Blanche, even if the apples he had painted had been ten times as beautiful.

What forces our interest is Cezanne's anxiety, that's Cezanne's lesson;

the torments of Van Gogh - that is the actual drama of the man. The rest

is a sham.”

Berger, John.”The Success & Failure of Picasso”; New York; 1980;

p.5; quoting Alfred H. Barr; “Picasso: Fifty Years of His Art”; Museum

of Modern Art, New York, 1946.

Berger perceptively places Picasso’s exalted view of

“artistic creativity” - as a remnant of the Romantics of the 19th

century, for whom “art” was a “way of life”. Berger goes on to show that

this was a form of a reaction to the bourgeois, monied ‘Midas” touch –

a touch that changes all relations including artistic relations – to one

of a mere commerce. While this exaltation of “creativity” was of value

to the Romantics, in the 20th century nexus of individual versus masses,

this self-centredness could be and was, hideously out of place:

Pablo Picasso – Early Years

Picasso was born in Spain, but lived and worked most

of his life in Paris. His artistic mediums included sculpture, graphic

arts, ceramics, poster design, as well as fine art. He was probably the

most famous and prolific artist of the 20th century. As a son of a painter,

he was a precocious master of line, even as a child. It is said that as

a baby, is said to have been ‘lapiz' - pencil. His work incorporated a

number of styles, and he denied any logical sequence to his art development:

'The several manners I have used in my art must not be considered as

an evolution, or as steps toward an unknown ideal of painting. When I have

found something to express, I have done it without thinking of the past

or future. I do not believe I have used radically different elements in

the different manners I have used in painting. If the subjects I have wanted

to express have suggested different ways of expression, I haven't hesitated

to adopt them.'

I. Chilvers, H. Osborne, D. Farr. "Oxford Dictionary of Art"; Oxford;

1977; p. 431.

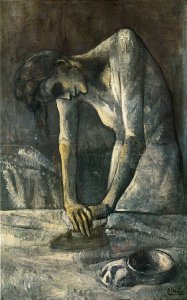

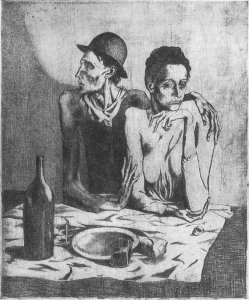

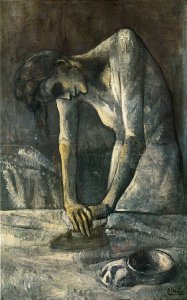

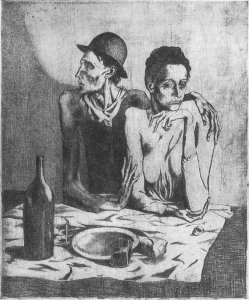

At this early stage (1900-1904) Picasso expressed artistic

sentiments on behalf of the under-priviliged. For example, during his "Blue

Period", he painted several examples of a realistic and moving art:

"he took his subjects from the poor and social outcasts, the predominant

mood of his paintings was one of at bottom opposed to the irrationalist

elements of slightly sentimentalized melancholy expressed through cold

ethereal blue tones (La Vie, Cleveland Museum of Art, 1903). He also did

a number of powerful engravings in a similar vein (The Frugal Repast, d

1904)." [See below].

I. Chilvers, H. Osborne, D. Farr. "Oxford Dictionary of Art"; Oxford;

1977; p. 431.

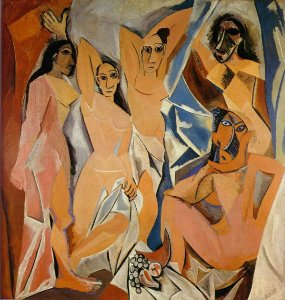

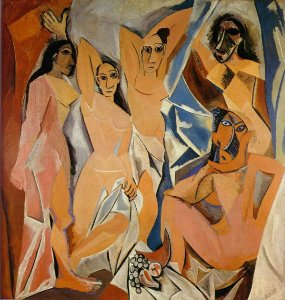

By 1904 Picasso now in Paris, was influenced by

the Fauvist movement, as well as African sculpture and Cezanne’s

works. He began to distort anatomical forms, in order to "disregard any

conventional idea of beauty" ("Les Demoiselles d’Avignon" (MOMA, New York,

1906-7)[ See below]. At that time, these results were not viewed favourably,

and "d’Avignon" was not publicly exhibited until 1937. But it marked the

start of Cubism, which Picasso began with Braque and Gris

from 1907 up to the First World War.

So what was Cubism? It was a movement begun by Picasso

with Braque, and later Gris, and was named after their tendency to use

cubic motifs, as can be seen above:

"Movement in painting and sculpture, … was originated by Picasso and

Braque. They worked so closely during this period - 'roped together like

mountaineers' in Braque's memorable phrase - that at times it is difficult

to differentiate their hands. The movement was broadened by Juan Gris,

…… the name originated with the critic Louis Vauxcelles (following a mot

by Matisse), who, in a review of the Braque exhibition in the paper Gil

Blas, 14 November 1908, spoke of 'cubes' and later of 'bizarreries cubiques'.

"

I.Chilvers, H. Osborne, D. Farr. "Oxford Dictionary of Art"; Oxford;

1977; p. 144.

The cubists rejected an "apparent" reality to be conveyed

by normal rules of perspective and modelling. They aimed to show all sides

of reality, by displaying a moving history of how objects look over time,

and from simultaneously observed but differing, vantage points. It was

a "cerebral" exercise therefore, and it rejected any simple notion of how

"an object looked":

"Cubism made a radical departure from the idea of art as the imitation

of nature that had dominated European painting and sculpture since the

Renaissance. Picasso and Braque abandoned traditional notions of perspective,

foreshortening, and modelling, and aimed to represent solidity and volume

in a two-dimensional plane without converting the two-dimensional canvas

illusionistically into a three-dimensional picture-space. In so far as

they represented real objects, their aim was to depict them as they are

known and not as they partially appear at a particular moment and place.

For this purpose many different aspects of the object might be depicted

simultaneously; the forms of the object were analysed into geometrical

planes and these were recomposed from various simultaneous points of view

into a combination of forms. To this extent Cubism was and claimed to be

realistic, but it was a conceptual realism rather than an optical and Impressionistic

realism. Cubism is the outcome of intellectualized rather than spontaneous

vision. "

I. Chilvers, H. Osborne, D. Farr. "Oxford Dictionary of Art"; Oxford;

1977; p. 144.

As a movement, following its’ birth with "Les Demoiselles

d’Avignon", it rapidly evolved into other movements – but it was one of

the key sources of abstractionism in art:

"The harbinger of the new style was Picasso's celebrated picture Les

Demoiselles d`Avignon (MOMA, New York, 1907), with its angular and fractured

forms. It is customary to divide the Cubism of Picasso and Braque into

two phases-Analytical' and 'Synthetic'. In the first and more austere phase,

which lasted until 1912, forms were analysed into predominantly geometrical

structures and colour was extremely subdued-usually virtually monochromatic

- so as not to be a distraction. In the second phase colour became much

stronger and shapes more decorative, and elements such as stencilled lettering

and pieces of newspaper were introduced into paintings .................Cubism,

as well as being one of the principal sources for abstract art, was infinitely

adaptable, giving birth to numerous other movements, among them Futurism,

Orphism, Purism, and Vorticism...."

I. Chilvers, H. Osborne, D. Farr. "Oxford Dictionary of Art"; Oxford;

1977; p. 144.

But all these new movements propound a view of life

that is "form-destroying". Picasso thus easily flips in and out

of several art movements, all the time exploring ever more "un-real" and

deconstructed forms. At the same time, he is intent upon eroding any sense

of a "unity" – whether of personality, of styles, view of the world etc.

All reflect the deep contradictions of 20th century capitalism:

"Cubism and constructivism, on the one side, and expressionism and

surrealism, on the other, embody strictly formal and form-destroying tendencies

respectively which now appear for the first time side by side in such sharp

contradiction. ...

Picasso, who shifts from one of the different stylistic tendencies

to the other most abruptly, is at the same time the most representative

artist of the present age. ...

Picasso's eclecticism signifies the deliberate destruction of

the unity of the personality; his imitations are protests against the cult

of originality; his deformation of reality, which is always clothing itself

in new forms, in order the more forcibly to demonstrate their arbitrariness,

is intended, above all, to confirm the thesis that "nature and art are

two entirely dissimilar phenomena." Picasso turns himself into a

conjurer, a juggler, a parodist, ..

And he disavows not only romanticism, but even the Renaissance, which,

with its concept of genius and its idea of the unity of work and style,

anticipates romanticism to some extent. He represents a complete break

with individualism and subjectivism, the absolute denial of art as the

expression of an unmistakable personality. His works are notes and commentaries

on reality; they make no claim to be regarded as a picture of a world and

a totality, as a synthesis and epitome of existence. Picasso compromises

the artistic means of expression by his indiscriminate use of the different

artistic styles just as thoroughly and wilfully as do the surrealists by

their renunciation of traditional forms. The new century is full of such

deep antagonisms, the unity of its outlook on life is so profoundly menaced,

that the combination of the furthest extremes, the unification of the greatest

contradictions, becomes the main theme, often the only theme, of its art."

Hauser, Arnold. "The Social history of Art – Naturalism, Impressionism,

The Film Age. Volume 4"; New York; nd; p.233-234.

Since Picasso is so adept technically, he can continue

to simply adopt and then drop styles as he pleases. In 1917 Picasso went

to Italy, where he was impressed by Classicism, and incorporated some features

of so-called "Monumental Classicism" into the work of the 1920’s

(Mother and Child), but he also became involved with Surrealism, and with

Andre Breton. The surrealists were interested in "irrationalist

elements, and exaltation of chance, and equally to the direct realistic

reproduction of dream or subconscious material." I. Chilvers, H. Osborne,

D. Farr. "Oxford Dictionary of Art"; Oxford; 1977; p.431.

During this time, he explored images of the Minotaur,

the half man half beast drawn from Cretan mythology. Now, the Spanish Civil

War erupted. This led to his most famous work, Guernica (Centro

Cultural Reina Sofia, Madrid, 1937), which was produced for the Spanish

Pavilion at the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1937 to express horror

and revulsion at the destruction by bombing of the Basque capital Guernica

during the civil war (1936-9).

By this time, Picasso had already become a very rich

man already:

“Picasso was rich. Dealers began to buy his work in 1906. By 1909 he

employed a aid with apron and cap to wait at table. In 1912, when he painted

a picture on a whitewashed wall in Provence, his dealer thought it was

worthwhile demolishing the wall and sending the whole painted piece intact

to Paris to be remounted by experts on a wooden panel. In 1919 Picasso

moved into a large flat in one of the most fashionable quarters of Paris.

In 1930 he bought the seventeenth-century Chateau de Boisgeloup as an alternative

residence. From the age of twenty-eight Picasso was free from money

worries. From the age of thirty-eight he was wealthy. From the age of sixty-five

he has been a millionaire.”

Berger, John.”The Success & Failure of Picasso”; New York; 1980;

p.5.

Guernica – The Bombing

On 26 April 1937, the German air force was asked by

General Franco to bomb the city of Guernica. This city was the ancient

heart of the Basque nation, an oppressed nation within the multi-national

state of Spain. It had resisted the Francoite fascists, and Franco was

determined to subdue it. The city had no defences, and no military importance.

The correspondent of ‘The Times’ reported on the destruction:

"Guernica, the most ancient town of the Basques and the centre of

their cultural tradition was completely destroyed yesterday afternoon by

insurgent air raiders. The bombardment of the open town far behind the

lines occupied precisely three hours and quarter, during which a powerful

fleet of aeroplanes consisting of three German types, Junkers and Heinkel

bombers and Heinkel fighters did not cease unloading on the town bombs.

And incendiary projectiles. The fighters, meanwhile, plunged low from above

the centre of the town to machine gun those of the civil population who

had taken refuge in the fields.

The whole of Guernica was soon in flames, except

the historic Casa de Juntas, with its rich archives of the Basque race,

where the ancient Basque Parliament used to sit. The famous oak of Guernica,

the dried old stump of 600 years and the new shoots of this century, was

also untouched. Here the kings of Spain used to take the oath to respect

the democratic rights (fueros) of Vizcaya and in return received

a promise of allegiance as suzerains with the democratic title of Senor,

not Rey Vizcaya."

Antony Blunt. "Picasso’s Guernica"; Toronto; 1969; Oxford & Toronto,

p.7-8.

Perhaps however the real measure of the horror is best

given by the first eye-witness account, from a priest – Father Alberto

de Onaindia:

"We reached the outskirts of Guernica just before five o'clock. The

streets were busy with the traffic of market day. Suddenly we heard the

siren, and trembled. People mere running about in all directions, abandoning

everything they possessed, some hurrying into the shelters, others running

into the hills. Soon an enemy airplane appeared ... and when he was directly

over the center he dropped three bombs. Immediately airwards we saw a squadron

of seven planes, followed a little later by six more, and this in turn

by a third squadron of five more. And Guernica was seized by a terrible

panic.

I left the car by the side of the road and we took

refuge in a storm drain. The water came up to our ankles. From our hiding

place we could see everything that happened without being seen. The airplanes

came low, flying at two hundred meters. As soon as we could leave our shelter,

we ran into the woods, hoping to put a safe distance between us and the

enemy. But the airmen saw us and went after us. The leaves hid us. As they

did not know exactly where we were, they aimed their machineguns in the

direction they thought we were traveling. We heard the bullets ripping

through branches and the sinister sound of splintering wood. The milicianos

and I followed the flight patterns of the airplanes, and we made a crazy

journey through the trees, trying to avoid them. Meanwhile, women, children,

and old men were falling in heaps, like flies, and everywhere we saw lakes

of blood.

I saw an old peasant standing alone in a field:

a machine-gun bullet killed him. For more than an hour these planes, never

more than a few hundred meters in altitude, dropped bomb after bomb on

Guernica. The sound of the explosions and of the crumbling houses cannot

be imagined. Always they traced on the air the same tragic flight pattern,

as they flew all over the streets of Guernica. Bombs fell by the thousands.

Later we saw bomb craters. Some were sixteen meters in diameter and eight

meters deep.

The airplanes left around seven o'clock, and then there

came another wave of them, this time flying at an immense altitude. They

were dropping incendiary bombs on our martyred city. The new bombardment

lasted thirty-five minutes, sufficient to transform the town into an enormous

furnace. Even then I realized the terrible purpose of this new act of vandalism.

They were dropping incendiary bombs to convince tie world that the Basques

had torched their own city. The destruction went on altogether for two

hour. and forty-five minutes. When the bombing was over the people left

their shelters. I saw no one crying. Stupor was written on all their faces.

Eyes fixed on Guernica, we were completely incapable of believing what

we saw."

In Martin, Russell. "Picasso’s War. The Destruction of Guernica, and

the Masterpiece that Changed the World"; 2002, New York; p. 40-42.

Colonel Wolfram von Richthofen, commanded the

Condor Legion, and planned that first blast bombs would destroy all city-centre

buildings; then that the townspeople would be strafed with machine-gun

fire; and finally, that incendiary bombs would set fire to the rubble.

Four days later, he reported his success:

"Gernika literally levelled to the ground. Attack carried out with

250-kilogram and incendiary bombs-about one-third of the latter. When the

first Junker squadron arrived, there was smoke everywhere already [from

von Moreau's first assault]; no, body could identify the targets of roads,

bridge, and suburbs, and they just dropped everything right into the center.

The 250s toppled houses and destroyed the water mains. The incendiaries

now could spread and become effective. The material of the houses: tile

roofs, wooden porches, and half-timbering resulted in complete annihilation....

Bomb craters can still be seen in the streets, simply terrific. Town completely

blocked off for at least 24 hours, perfect conditions for a great victory,

if only the troops had followed through."

In Martin, Russell. "Picasso’s War. The Destruction of Guernica, and

the Masterpiece that Changed the World"; 2002, New York; p. 42-43.

Russell Martin points to the innovative strategy that

was utlized of air-raid induced terror:

"The three-hour campaign had been efficient, accurate, highly effective,

and it was precisely what was proscribed in German military strategist

M.K.L. Dertzen's Grundsdtze der Wehrpolitik, which had been published two

years before and which von Richthofen had taken very much to heart: "If

cities are destroyed by flames, if women and children are victims of suffocating

gases, if the population in open cities far from the front perish due to

bombs dropped from planes, it will be impossible for the enemy to continue

the war. Its citizens will plead for an immediate end to hostilities."

In Martin, Russell. "Picasso’s War. The Destruction of Guernica, and

the Masterpiece that Changed the World"; 2002, New York; p. 42-43.

Guernica – The Painting

Picasso had not been especially political up to this

time, although as a youth in Barcelona the vigorous anarchist movements

there had influenced him. But with the onset of the Spanish Civil War,

Picasso took sides. In May 1937 he made his position clear in a public

statement:

"The Spanish struggle is the fight of reaction against the people,

against freedom. My whole life as an artist has been nothing more than

a continuous struggle against reaction and the death of art. How could

anybody think for a moment that I could be in agreement with reaction and

death? When the rebellion began, the legally elected and democratic republican

government of Spain appointed me director of the Prado Museum, a post which

I immediately accepted. In the panel on which I am working which I shall

call Guernica, and in all my recent works of art, I clearly express my

abhorrence of the military caste which has sunk Spain in an ocean of pain

and death ...."

Barr, Alfred. "Picasso: Fifty Years of His Art"; New York; 1946; p.202;

cited by Blunt A; Ibid; p. 9.

"' No: painting is not there just to decorate the walls of a flat. It

is a means of waging offensive and defensive war against the enemy."

Cited at: http://www.tamu.edu/mocl/picasso/tour/t05c.html

He immediately did a pair of etchings entitled Sueho

y mentira de Franco (‘Dream and Lie of Franco) which he issued with an

accompanying poem. In January 1937, the Republican elected Government,

invited Picasso to paint a mural for the Spanish Pavilion in the International

Exhibition of Paris in 1938. Following the bombing of Guernica, Picasso

worked in a frenzy completing the huge work in ten days.

The cover of "Alliance Marxist-Leninist" Issue 52 shows the painting.

But for a larger view go here:

Web-site for Guernica at: http://www.arts.adelaide.edu.au/personal/DHart/Images/WarArt/Picasso/Guernica/Guernica.JPG

Blunt describes the large canvas as follows:

"The painting is on canvas and measures 11 ft. 6 in. by 25 ft. 8 in.

It is almost monochrome, that is to say, it is executed in various shades

of grey, varying from a completely neutral tint to slightly purplish and

bluish greys at one extreme, and brownish greys at the other.

The scene takes place in darkness, in an open space surrounded by schematically

indicated buildings, which presumably stand for a public square in the

town of Guernica. At the top is a strange lamp in the form of an eye, with

an electric bulb as the iris.

The actors in the scene fall into two groups. The active protagonists

are three animals - the bull, the wounded horse, and the winged bird just

visible in the left background-and two human beings, the dead soldier,

and the woman above and to the right, who leans out of a window and holds

out a lamp to illuminate the whole stage. They are accompanied by a sort

of Greek chorus of three women: the screaming mother carrying a dead baby

on the left, the woman rushing in from the right, and above her one falling

in a house which is collapsing in flames.

These figures - human and animal - and the symbolism attached to them

were not evolved at a single blow but have a long and complicated history,

not only in the work of Picasso himself but in European art of earlier

periods."

Blunt, Antony . "Picasso’s Guernica"; Toronto; 1969 OUP, p.13

Apart from a general sense of horror -what does it all

mean? What are the bull and the horse doing here so prominently?

"As regards the meaning of the picture, Picasso has only supplied

a slight clue about the central symbols. The horse, he said in an interview,

represents the people, and the bull brutality and darkness. When pressed

by his interlocutor to say whether he meant that the bull stood for Fascism,

he refused to agree and stuck to his original statement. … These indications

are tantalizingly slender, but it is possible, by a study of Picasso's

previous work, particularly in the 1930's, to deduce more about the symbols

used in Guernica and about the artist's intentions in general. The central

theme, the conflict between bull and horse, is one which has interested

the artist all his life. ……….."

Blunt, Antony . "Picasso’s Guernica"; Toronto; 1969; p.14.

Prior to Guernica, Picasso had long been depicting battles

between good and evil, where the Minotaur takes a prominent place. But

these symbolic interpretations are much less important than the overall

first impact – of the weeping women. There can be little doubt that any

spectator who is first shown this picture more likely reacts immediately

to the wailing women – one with an obviously dead child, one in a burning

house, and the dead or gravely injured soldier holding a weapon who is

being trampled by a terrified horse. The general effect is one of a terrible

searing scene. Moreover, an original draft had an equally potent image

– a clenched fist:

"In.. . . . the drawing of 9 May … . . the main interest is now focussed

on the dead soldier, who fills the whole left-hand part of the foreground,

lying with his head on the right, his left hand clasping a broken sword,"

his right arm raised and his fist clenched. That is to say, Picasso has

taken the theme of the raised arm with clenched fist, which in the drawing

played a quite minor part in a corner of the composition, and has given

it a completely new significance by attaching it to the central figure

of the composition. The arm of the soldier now forms a strong vertical,

which is emphasized by the axis of the lamp, continued downwards in a line

cutting across the body of the horse, and by another vertical line drawn

arbitrarily to the left of the arm. The vertical strip thus formed is made

the basis of the geometrical scheme on which the composition is built up."

Blunt, Antony: "Picasso’s Guernica"; Toronto; 1969 OUP, p.39.

The drawing can be seen at: http://www.arts.adelaide.edu.au/personal/DHart/Images/WarArt/Picasso/Guernica/DoraMaarsPhotos/State1-11May1937.JPG

However Picasso then removed the raised arm. Why?

What we can be sure of is that at that time Picasso was not associated

with the Communist party, and the symbol of the clenched fist was and is

- an explicitly communist one. Therefore, the overall sense of the painting

remains one of a horror – and not that of a RESISTANCE to the hells

of war.

And naturally, the "distortions of forms" – the late

Picasso speciality – remains. But – having said that - what impact has

the painting had on the numerous people who have seen it or its reproduction?

An interesting experience is to watch those who are looking at this gigantic

painting – they are mesmerised and yet, horrified at the same time.

There is absolutely no doubt that the picture has become iconic

in its symbolic rejection of war and the brutal inhumanity of war.

For those who might still be sceptical of this viewpoint,

it should be remembered that during the prelude to the inhumane, and illegal

2003 war against Iraq, a tapestry copy of "Guernica" – that hangs in the

foyer at the United Nations HQ at New York, was shrouded during televised

interviews.

Why does it seem that this painting evokes such resonant

feelings? After all, it is in its form-distortions – anti-realistic. In

fact "abstract" painting rarely evokes a "positive" audience reaction.

Recall for instance the furore as the "critics" - the servants of the capitalist

classes waxed eloquent about the piles of bricks at the Tate – the public

roared its’ incomprehension and its’ disapproval. But this has not ever

happened with "Guernica". Why?

It is possible that people have become simply more

visually sophisticated than they used to be – under the influence of mass

printings. Or possibly the knowledge of what happened at Guernica is so

widespread – that people can make a quick connection between the intent

of the painting – despite the distortion of forms. But, a third point has

to be made. That is that perhaps despite the bias of the painter, whose

loyalty to "form-distortion" was so deep – it is in fact pretty "realistic".

The horse screaming in agony is – evidently just that. The women howling

– can be heard. The heat on the woman burning the bomber house – is felt

scorching us. The sounds of the horse trampling on the dead soldier – are

bone-jarringly "real".

Maybe Picasso was a "cubist". But he left his intellectualised

system to one side when he painted this picture.

Picasso also made other great paintings that attacked

war, [See "The Charnel House"; MOMA, New York, 1945] and the later Korean

War [ "Korean women and children being butchered by white men - Massacre

in Korea" - see below:]

All show marked ‘form-distortion’, but they nonetheless, do convey

a clear message. In fact, the non-realistic pictures do resonate. The editors

of the ‘Oxford Dictionary’, claim that:

"In treating such themes Picasso universalized the emotional content

by an elaboration of the techniques of expression which had been developed

through his researches into Cubism."

I. Chilvers, H. Osborne, D. Farr. "Oxford Dictionary of Art"; Oxford;

1977; p. 144.

Clearly, these works are not ‘realist’ in any usual

meaning, but their meaning is surely explicit. So – are these propagandist

posters, or are they art? We would argue that they are more within the

realm of progressive propaganda. But, the boundary line is certainly very

narrow.

Impact of Picasso and Guernica on Russian Discussions Upon Socialist

Realist Art

A mythology prevails, that there was no discussion -

nor knowledge of Western art movements in the socialist years of the USSR

(up to 1953). But this is patently false, as there is absolutely no doubt

that the Russian artistic scene, was affected by currents in the West.

Indeed, the height of knowledge and sensible debates about these various

movements is the lie to the general bourgeois line that "there was no debate"

and "purely dictatorship" in the USSR. Artistic events in the West

were treated very seriously and openly. Undoubtedly post-Second World War

there was a renewed debate about the principles of ‘Socialist Realism’:

“At the ninth plenum of the orgkomitet (Organising Committee of the

Union of Soviet Artists) held May 1945, some of speakers from the floor

brought up the question of innovation in painting, suggesting a new openness

to questions of form.... Even court painters and official spokesmen

of socialist realism appeared with new faces. The critic V Gaposhkin made

a visit to Alexandr Gerasimov's studio and praised highly his unfinished

painting of “A Russian Communal Bath' - a major composition of female nudes

with no ideological pretext (plate 230). .........

That the mood among some artists and critics, was distinctly

rebellious may be may be gleaned from a lecture, entitled ‘The Problem

of the 'Impressionism & the problem of the Kartina', delivered by Nikolai

Punin to the Leningrad artists' union on 13 April 1946 - and from the reaction

to it.

Punin's address was an attempt to install impressionism

as the basis for the work of Soviet painters; it amounted not only to a

revision of the attitude to impressionism which had been imposed in the

art press after the debates of 1939-40, but also to a rejection of some

of the entrenched principles of socialist realism. He stressed the variety

apparent in the painting of the impressionists extolled them as 'honest'

and 'contemporary'. He criticised the characterisation of impressionism

as some kind of a system..”.

Cullerne Bown, Matthew. “Socialist Realist Painting”; New Haven;1998;

p.223.

Picasso and his evident partisanship, as expressed in

‘Guernica’ became a part of the debate in the USSR:

“At the discussion on 26 April the artist Petr Mazepov pointed out

that impressionism led to the formalist art of cubism and fauvism, in which

'there is no social struggle, the class soul, the party soul, the great

soul of the people is absent'.' At this point Mazepov was interrupted from

the floor: 'And Picasso?' 'And Cezanne?" And " Guernica, he's a Communist,

a party member." A little later Mazepov was interrupted again: 'An artist

doesn't have to take up a proletarian position to express his idea'. .................

Over the course of both days' debate, Punin received broad support

from well-known Leningrad painters such as Pakulin and Traugot, and from

voices from the floor. He summed up on 3 May: 'If we take cubism or futurism,

if we take the work of Picasso, then I personally do not see any formalism

in this'.”

Cullerne Bown, Matthew. "Socialist Realist Painting"; New Haven; 1998;

p.223.

Punin's denial of "formalism: in the works of cubism, or futurism

- is untenable. Punin was using the works of the 1930's of Picasso,

that had already mutated away from "non-realistic" painting. Actually,

it is very telling that the argument "What about Guernica?" – could be

used in the midst of this discussion. Even the staunchest supporter of

the principles of socialist realism in the USSR, simply had to concede

that the painting had emotional power. But the use of Picasso's open allegiance,

by various revisionist sections of the French Communist party even more

blatantly.

Post Second World War - ‘Becoming a communist, Picasso hoped

to come out of exile'.

Already, his painting of Guernica had shown that Picasso was a republican.

During the war years, he stayed in Nazi occupied Paris. On the liberation

of Europe, Picasso was to show very publicly his allegiance to the Communist

party:

"On October 4 1944, less than six weeks after the liberation of Paris,

Pablo Picasso, then 63, joined the French Communist party. To his surprise,

the news covered more than half of the front page of the next day's L'Humanité,

the party's official newspaper, overshadowing reports of the war…….. "Shortly

after, in an interview for L'Humanité, Picasso claimed that he had

always fought, through the weapons of his art, like a true revolutionary.

But he also said that the experience of the second world war had taught

him that it was not sufficient to manifest political sympathies under the

veil of mythologising artistic expression.

"I have become a communist because our party strives more than any

other to know and to build the world, to make men clearer thinkers, more

free and more happy. I have become a communist because the communists are

the bravest in France, in the Soviet Union, as they are in my own country,

Spain. While I wait for the time when Spain can take me back again, the

French Communist party is a fatherland for me. In it I find again all my

friends - the great scientists Paul Langevin and Frédéric

Joliot-Curie, the great writers Louis Aragon and Paul Eluard, and so many

of the beautiful faces of the insurgents of Paris. I am again among brothers."

Five days after joining the party Picasso appeared at a ceremony at the

Père Lachaise cemetery, organised as a joint memorial for those

killed during the Commune of 1871 and in the Nazi occupation of Paris."

Gertje R Utley. "Picasso was one of the most valued members of the

French Communist party - until a portrait of Stalin put him at the centre

of an ideological row". October 21, 2000 The Guardian; http://www.guardian.co.uk/saturday_review/story/0,3605,385610,00.html

Elsewhere he rhetorically asked:

“Have not the Communists been the bravest in France, in the Soviet

Union, and in my own Spain? How could I have hesitated? The fear to commit

myself? But on the contrary I have never felt freer, never felt more complete.

And then I have been so impatient to find a country again: I have always

been an exile, now I am no longer one: whilst waiting for Spain to be able

to welcome me back, the French Communist Party have opened their arms to

me, and I have found there all whom I respect most, the greatest thinkers,

the greatest poets, and all the faces of the Resistance fighters in Paris

whom I saw and were so beautiful during those August days; again I am among

my brothers.”

Berger, John.”The Success & Failure of Picasso”; New York; 1980;

p.173.

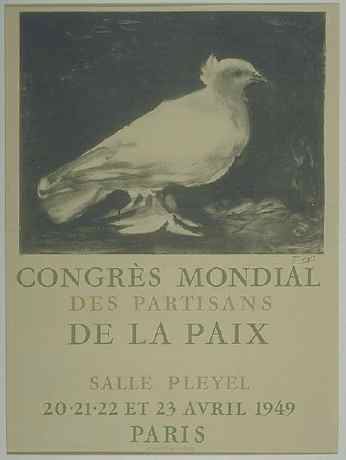

His allegiance extended to numerous art-related activities.

His efforts were recognised by a Stalin Prize, for his famous Poster for

Peace, using the image of a dove [See below].

“He also presided over the infamous gathering of the Comité

Directeur du Front National des Arts, which drew up the list of artists

to be purged for collaborationist activities during the occupation. In

1950 he was awarded the Stalin prize for his involvement in the Mouvement

de la Paix, for which he had designed the emblem of a dove. The movement,

……. was inaugurated in Wroclaw under the aegis of Andrey Zhdanov,

secretary of the Soviet central committee”.

Gertje R Utley. Ibid;. October 21, 2000 The Guardian;

http://www.guardian.co.uk/saturday_review/story/0,3605,385610,00.html

In addition he was lavish with his money:

“he generously donated time and money to the FCP and associated organisations.

He marched with the Front National des Intellectuels and the Front National

Universitaire and accepted honorary positions on boards and in organisations.

His contributions mostly took the form of paintings donated for sale. In

November 1956 alone, the dealer Kahnweiler wrote that he gave on Picasso's

behalf a cheque for FFr3m for Christmas gifts for Enfants des Fusillés

de la Résistance, FFr500,000 for the Comité de la Paix, FFr300,000

for the Patriote de Toulouse, FFr750,000 more for the children of war victims

and FFr3m (half a million more than the previous year) for a yearly Communist

party event. (To give some perspective to these figures, Chrysler bought

Picasso's Le Charnier in 1954 for FFr5m.) “

Gertje R Utley. Ibid;. October 21, 2000 The Guardian;

http://www.guardian.co.uk/saturday_review/story/0,3605,385610,00.html

So upon Stalin’s death, it was not un-expected that

he would be asked to paint his picture. He had pervasively been asked –

on Stalin’s 70th birthday – and refused. This time he agreed. However an

orchestrated campaign of vilification suggested that the portrait was “an

affront to Stalin” as it “neglected to reflect the emotions of the people”.

Picasso had wanted a portrait of “a man of the people”. The French Communist

Party was of course under revisionist control at this time. As we have

previously described, the revisionists wished to perpetuate a “cult of

personality”. Picasso had reverted to a ‘realistic’ style, at a most inconvenient

time for them, and in a most inconvenient manner. He “had to be rebuked”:

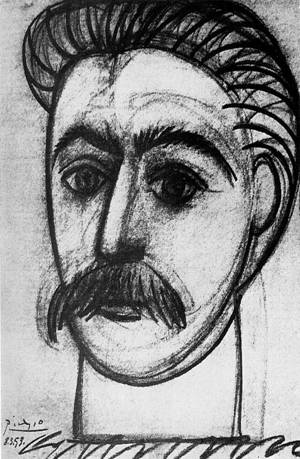

“In 1953 …………. Stalin died on March 5. Aragon and editor Pierre Daix

were preparing an issue of the communist journal “Les Lettres Françaises”

when the news broke. Aragon immediately sent a telegram to Picasso.

.. requesting a drawing of Stalin. Daix and Gilot knew that Picasso,

who until then had successfully foiled any hope that he would paint a portrait

of Stalin, could not refuse this time. The artist's homage for Stalin's

70th birthday in 1949 had been nothing more than a drawing of a glass raised

to the dictator's health, which had shocked the party faithful with its

breezy caption, "Staline à ta santé". ………

He seems to have used old newspaper photographs

as a reference. The portrait shows the young Stalin, face framed by thick,

cropped hair, mouth partly hidden under a bushy moustache. The eyes under

the strong eyebrows are those of a dreamer and offset by the prominent

jawline. Picasso told Geneviève Laporte, ……… that he had wanted

to show Stalin as a man of the people, without his uniform and decorations.

……… Aragon and Daix were relieved to find the portrait to their liking.

Daix opted for the neutral caption "Staline par Pablo Picasso, March 8

1953". …

The first negative reaction came from the employees

of France Nouvelle and L'Humanité, the two papers that shared the

same building as Les Lettres françaises, who were appalled by what

they considered an affront to Stalin. Daix suspected - correctly, as it

turned out - that this was instigated by the party leaders, who saw publication

of the portrait as an

incursion against the personality cult, and by Auguste Lecur, hardline

party secretary, who welcomed this opportunity to chastise Aragon and Les

Lettres françaises for the relative independence they claimed. .

. . .

From the moment the paper appeared at kiosks on

March 12, the editorial offices were flooded with outraged calls. On March

18 1953, a damaging communiqué appeared in L'Humanité from

the secretariat of the French Communist party, "categorically" disapproving

publication of the portrait "by comrade Picasso". ….. Aragon was obliged

to publish the communiqué in the following issue of Les Lettres

françaises, as well as a self-criticism in L'Humanité. The

major reproach …………… was that the portrait neglected to reflect the emotions

of the public - "the love that the working class feel for the regretted

comrade Stalin and for the Soviet Union" - and that it did not do justice

to the moral, spiritual, and intellectual personality of Stalin.“

Gertje R Utley. Ibid;. October 21, 2000 The Guardian;

http://www.guardian.co.uk/saturday_review/story/0,3605,385610,00.html

But Picasso refused to rise to the bait, and refused

to attack the party.

“Picasso, besieged by journalists eager to have him admit that his

portrait sought to mock Stalin, refuted any such suggestion. nor did the

attacks against him entice Picasso to disparage the party, as some had

hoped. “Despite various reports that quoted Picasso as saying that one

did not criticise the flowers that were sent to the funeral or the tears

that were shed, Gilot [Picassos’ then lover – editor] recalled a more detached

attitude. According to her, Picasso replied that aesthetic matters were

debatable, that therefore it was the party's right to criticise him and

that he saw no need to politicise the issue. "You've got the same situation

in the party as in any big family," he said. "There is always some damn

fool to stir up trouble, but you have to put up with him."

Gertje R Utley. Ibid;. October 21, 2000 The Guardian;

http://www.guardian.co.uk/saturday_review/story/0,3605,385610,00.html

In private, Picasso gave a rather amusing – if somewhat

coarse – attack on the bureaucratic slavish mentality behind this imbroglio:

“In conversation with Daix, who was sent by Aragon to appease him,

Picasso speculated:

"Can you imagine if I had done the real Stalin, such as he has become,

with his wrinkles, his pockets under the eyes, his warts.. A portrait in

the style of Cranach! Can you hear them scream? 'He has disfigured Stalin!

He has aged Stalin!'" He continued: "And then too, I said to myself, why

not a Stalin in heroic nudity?... Yes, but, Stalin nude, and what about

his virility?... If you take the pecker of the classical sculptor... So

small... But, come on, Stalin, he was a true male, a bull. So then, if

you give him the phallus of a bull, and you've got this little Stalin behind

his big thing they'll cry: But you've made him into a sex maniac! A satyr!

"Then if you are a true realist you take your tape measure and you

measure it all properly. That's worse, you made Stalin into an ordinary

man. And then, as you are ready to sacrifice yourself, you make a plaster

cast of your own thing. Well, it's even worse. What, you dare take yourself

for Stalin! After all, Stalin, he must have had an erection all the time,

just like the Greek statues... Tell me, you who knows, socialist realism,

is that Stalin with an erection or without an erection? "

When in the summer of 1954 (after Stalin’s death) ……..Picasso, thinking

aloud, asked Daix: "Don't you think that soon they will find that my portrait

is too nice?" On another occasion, he reflected: "Fortunately I drew the

young Stalin. The old one never existed. Only for the official painters."

Gertje R Utley. Ibid;. October 21, 2000 The Guardian;

http://www.guardian.co.uk/saturday_review/story/0,3605,385610,00.html

What is even more interesting – is that despite his

“saison en enfer” (season in hell) – Picasso never recanted his allegiance

to the party. Even with the social-imperialists attacks on both Hungary

(1956) or Czechoslovakia (1968):

“Picasso later called the year 1953 his "saison en enfer" – his season

in hell. He admitted to some friends how shaken he had been by the accusations

and humiliations of the scandal. The year is widely believed to signal

the end of Picasso's political commitment. Yet while his cooperation with

the party was never again as close as it had been in the years 1944-53,

his commitment did not stop. He continued to produce drawings for the press

and for poster designs, made supportive appearances at party events, and

readily signed petitions and protest declarations initiated by the party.

He also never discontinued his financial support. While many left because

of the party's attitude during the Hungarian uprising in 1956, Picasso

reaffirmed his loyalty. In an interview with the art critic Carlton Lake

in July 1957, he once again confirmed his belief in communism and his intention

never to leave the party. In 1962 he was awarded the Lenin prize. In August

1968, speaking with friends, he deplored the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia,

but failed to do so publicly. At the end of that year, he refused once

again to speak out against his long-held political beliefs.‘

Gertje R Utley. Ibid;. October 21, 2000 The Guardian;

http://www.guardian.co.uk/saturday_review/story/0,3605,385610,00.html

He clearly believed the lies of the revisionist

Khruschev, given out at this so-called “secret speech”. But he asked whether

“And the workers, are they still masters of their factories, and the peasants,

the owners of their land?” :

“After Khrushchev's "secret speech" at the 20th congress of the Soviet

Union's Communist party, in February 1956, in which he reported on the

crimes of Stalin's tyranny, it became impossible for anybody to claim ignorance.

Picasso apparently was appalled: "While they asked you to do ever more

for the happiness of men... they hung this one and tortured that one. And

those were innocents. Will this change? Picasso's response to detrimental

news from the Soviet Union was: "And the workers, are they still masters

of their factories, and the peasants, the owners of their land? Well then,

everything else is secondary - the only thing that matters is to save the

revolution”.

Gertje R Utley. Ibid;. October 21, 2000 The Guardian;

http://www.guardian.co.uk/saturday_review/story/0,3605,385610,00.html

His answer was the workers were still in charge. Of

course he was tragically wrong. But then – he was an artist, albeit a flawed

one, always twisting away from reality. In the end he was somewhat ‘straightened’

by his late found political allegiance. But – he was still only an artist

- and not a political theorist or leader of the working classes. What in

an artist is excusable – is inexcusable in those who claim to be ‘leaders

of the vanguard of the working class’. Therefore we will agree, if we are

charged that we view Picasso with a benign eye. We would simply counter

that this is the same ‘benign eye’ that Marx turned on artists in general,

saying of the poet Ferdinand Freiligarth for instance:

"Write Freiligarth a friendly letter. nor need you be over-careful

of paying him compliments, for poets, even the best of them, are all plus

au moins [more or less], courtisanes and il faut les cajoler, pour les

faire chanter [one must cajole them to make them sing]....

A poet , whatever he may be as an homme (man), needs applause and ADMIRATION.

This I believe , peculiar to the genre as such. you should

not forget the difference between a "poet" and a "critic".

Marx to Joseph Weydemeyer, January 16, 1852. Volume 39: Collected Works;

Moscow; 1983; p.8.

See also Marx and Engels on Art: Marx

Art at: http://harikumar.brinkster.net/SocialistArt/Final-ME_LASSALLE.htm

Equally, we cannot accept the line of John Berger, who

writes:

“But as an artist with all his powers he was nevertheless wasted.”

Oddly, Berger writes this despite having already pointed

out that Picasso had renewed himself by joining the party:

“As a result of Picasso's joining the Communist Party and taking part

in the peace movement, his fame spread even wider than before. His name

was quoted in all the socialist countries. His poster of the peace dove

was seen on millions of walls and expressed the hopes of all but a handful

of the people of the world. The dove became a true symbol: not so much

as a result of Picasso's power as an artist (the drawing of the dove is

evocative but superficial), but rather as a result of the power of the

movement which Picasso was serving. It needed a symbol and it claimed Picasso's

drawing. That this happened is something of which Picasso can be rightly

proud. He contributed positively to the most important struggle of our

time. He made further posters and drawings. He lent his name and reputation

again and again to encourage others to protest against the threat of nuclear

war. He was in a position to use his art as a means of influencing people

politically, and, in so far as he was able, he chose to do this consciously

and intelligently. I cannot believe that he was in any way mistaken or

that he chose the wrong political path.”

Berger, John.”The Success & Failure of Picasso”; New York; 1980;

p.173-5.

Well, Picasso bloomed anew with the power of the peoples

vision. How can Berger recognising this, then say that Picasso was wasted

artistically? In the last period of his life, apart from the posters and

the variations on the dove of peace he did, Picasso really only painted

upon the ceramics made by others. In contrast to Berger, we might suggest

that it was his political artistic work, that kept him ‘artistically alive’.

Conclusion:

We argue that Picasso ultimately was on the side of

the working classes. A "champagne socialist" he may have been – but he

did not need to do what he did. As to the worth of his art - where he retained

realist images and forms, he showed a power that people understood. But

he was constantly reverting to decadent forms and images that placed at

an immediate distance between the people and his art. At his best, he moved

people.

And in that troubling work – "Guernica" – he undoubtedly,

has moved and affected generations who have seen it. Again – it is patently,

not a piece of "socialist art" – but despite its obvious anti-realist forms,

it conveys a very real, and realistic message:

Bibliography

Used In this article

Berger, John.”The Success & Failure of Picasso”; New York; 1980;

Blunt, Antony. "Picasso’s Guernica"; Toronto; 1969.

Chilvers, I; H. Osborne, D. Farr. "Oxford Dictionary of Art"; Oxford;

1977;

Cork, Richard "A Bitter Truth – Avant Garde Art & The Great War;

London 1994; Cullerne Bown, Matthew. "Socialist Realist Painting"; New

Haven;1998;

Hauser, Arnold. "The Social history of Art" – Volume 4: 'Naturalism,

Impressionism, The Film Age'"; New York; nd;

Martin, Russell. "Picasso’s War. The Destruction of Guernica, and the

Masterpiece that Changed the World"; 2002, New York.

Marx to Joseph Weydemeyer, January 16, 1852. Volume 39: Collected Works;

Moscow; 1983.

Utley, Gertje R. "Picasso was one of the most valued members of the

French Communist party - until a portrait of Stalin put him at the centre

of an ideological row". October 21, 2000 The Guardian; http://www.guardian.co.uk/saturday_review/story/0,3605,385610,00.html

Recommended:

Utley Gertje R "Picasso: The Communist Years"; Yale University Press,

2000.

Web-sites (NB: All web addresses were correct at time of writing).

"On Line Picasso Project" - a very comprehensive site on Picasso and

his works. http://www.tamu.edu/mocl/picasso/tour/t60.html

Art and war – a wonderful site http://www.arts.adelaide.edu.au/personal/DHart/ResponsesToWar/Art/StudyGuides/Picasso.html

END