ALLIANCE 53 August 2004

AESTHETICS AND REVOLUTION - ESSAYS AND TALKS

VIETNAMESE REVOLUTIONARY ARTGo to http://www.allianceML.com/AllianceIssues/A2004/ALLIANCE53.htm

For Other Parts of This issue of Alliance 53

Introduction

Western Artists and revolutionaries, are familiar with the socialist realist traditions of the USSR, Albania and of China. They also have a deep affection and respect for revolutionary painting from the Spanish Civil War, and from the South American continent especially from Mexico and Cuba. Curiously, art arising from the heroic struggles of the Vietnamese peoples, is much less well known. This is a shame, since the long war of national liberation, resulted in a plethora of great art.

Ho Chi Minh’s shrewd and insightful leadership of the Vietnamese national bourgeois liberation struggle, built a successful United Front. This was dependent upon the recognition that “many currents” would help move Vietnam into independence. A striking example of this viewpoint, is Ho Chi Minh’s view of Confucius, Jesus and Marx as “close friends”:

“The teachings of Confucius have a strong point, i.e., self-improvement of personal virtue. Jesus’ Bible has a strong point, i.e., noble altruism. Marxism has a strong point, i.e. a dialectical working method. Ton Dat Tien’s teaching has a strong point, i.e.Fe; their policies are suited to the conditions in our country, Did Confucius, Jesus, Marx, and Ton Dat Tien share common points? Yes. They all pursued a way to bring happiness to human beings and benefit to society. If they were all alive today, and if they were grouped together, I believe that they would live together in harmony like close friends. I try to become their pupil“.

Ho Chi Minh 1949. Plaque in Ho Chi Minh Museum, July 2004.

With this “broad church” philosophy, Ho Chi Minh succeeded in welding such a powerful anti-imperialist front. Unsurprisingly even the art in the clearly revolutionary phases of this broad front, also reflects a broad range of styles, and even at times of contents. Perhaps this is not surprising, since the Indochinese dominant French imperialism had already stimulated interest in the French art movements.

This article outlines and illustrates some developments in visual arts over the modern era. We apologise that it cannot be anything more than a very brief introduction.

A short background to the traditional arts, showing their legacy to the modern era, may be helpful.

Ancient Vietnamese Art

Naturally, the art history of the Vietnamese peoples is commensurate with their ancient story. The traditional arts in Vietnam faced the ravages of wars and little other than architectural edifices, and some sculptures and pottery, now exists. This shows the mark of a tension between external influences - Chinese and Indian - and more ‘native’ royalty sponsored arts. Largely it was the Cham dynasty that was heavily influenced by Indian art, and remaining sculptures show remarkable similarity.

Another major cultural import was Buddhism, via India directly, but also via South China. Buddhism has left a long lasting artistic and intellectual legacy in the many temples and pagodas that still survive in virtually every village. All these external influences were absorbed, such that by the 10th –11th centuries, the dominant artistic expressions relied upon Chinese Han traditions.

This absorption can be vividly seen in architecture, both in construction styles, and in intellectual legacy. This is vividly exemplified by the Temple of Literature founded in the 11th century. As the official tour plaque says of this shrine to Confucius, his four disciples and the ten learned ones:

“The Temple of Literature was the biggest centre in the country in feudal times, contributing to the training of thousands of scholars for the nation. It was worthy of being called the First University“.It should not surprise that this plaque lauds Confucius (551-479 BC -- Wade-Giles K'ung-fu-tzu or Pinyin Kongfuzi). Although Confucius is regarded as a reactionary in the current era, his contribution to welding a state in China is not challenged. And above all Ho Chi Minh was a dedicated nationalist, whose first mandate was to recognise important steps in the development of Vietnam into a modern, strong, independent and united nation, bridging the so-called three kys (parts of Vietnam).

Plaque, Temple of Literature, Hanoi July 2004.

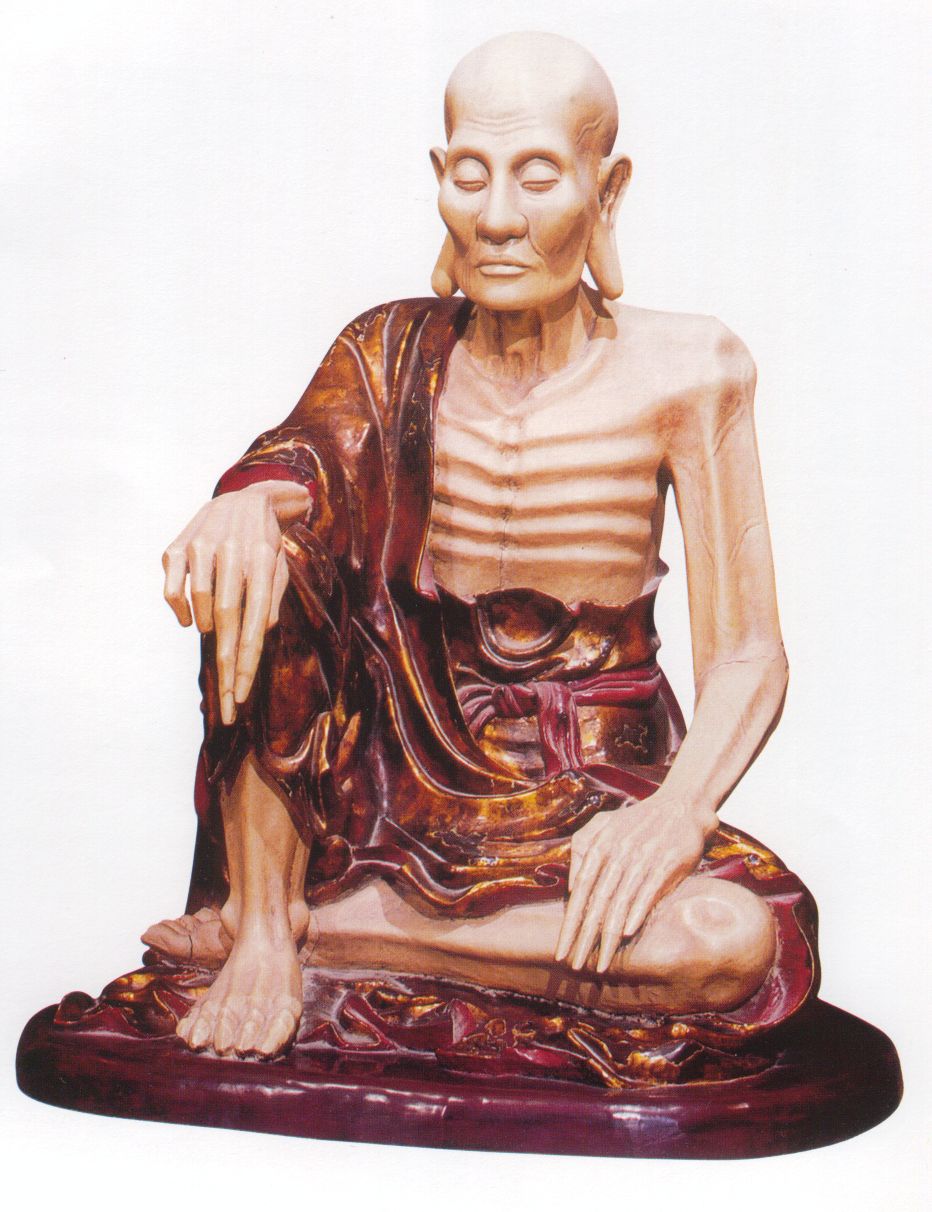

The existing legacy that we are aware of from Vietnamese arts rests primarily upon porcelains and ceramics, sculpture, architecture, and folk-art traditions. Of these a large mystical non-realist tradition was dominant, incorporating dragons and mythical beings. But they did nonetheless develop realist themes amidst the myths. So even the depictions of the Buddha show a real human shape and a real human expression [Plate 1]. This version of the Bhudda shows him starving but peaceful in meditation.

Notable in these statues is the covering of the wood, with several layers of lacquer [See below].

Plate 1: Statue of Sakyamuni on A Snow Mountain 1794; Height 137 cm

From:

Editor: Cao Trong Thiem, “Bao Tang My Thuat Viet Nam”;

Vietnam Fine Arts Museum; nd; p.43

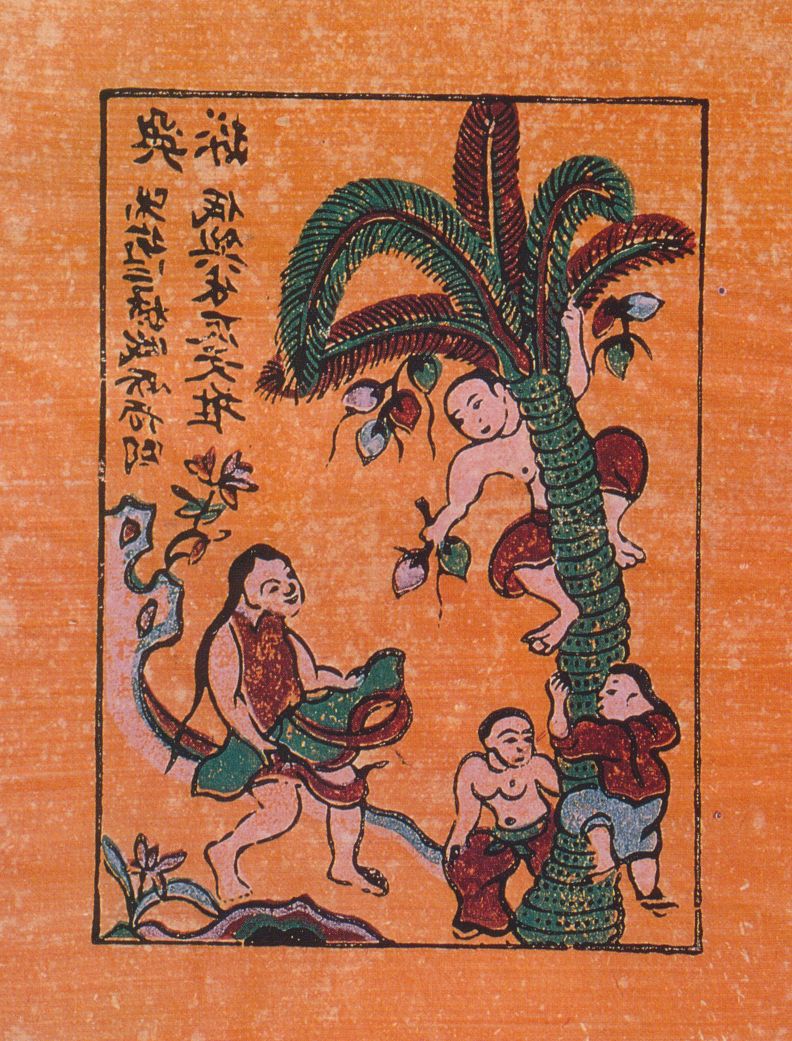

Given the ordinary peasants’ tendency to reduce all pretensions to an earthy reality, folk art usually took an explicitly realist form. The folk art illustrated life’s vagaries with a number of human motifs, as can be seen in the wood-cut traditions of Dong Ho village in Ha Bac Province [Plate 32]. This tradition was to re-surface with the development of poster art in the national revolutionary period.

Plate 2: Catching Coconuts (paper wood-cut print);

Cao Truong Theim; Ibid; p.51

Many of these techniques as developed over ancient times, left reservoirs of skills that were to find a new use in an entirely different set of traditions emanating from Western art and from the traditions of Socialist Realism. The ancient arts will not be further discussed here.

We will now focus, on the visual arts over the modern era.

Beginnings of Western Type Painting in Vietnam

Under French colonial domination at the turn of hte 19th - 20th centuries, Indochinese intellectuals were drawn to French and Western art movement. This was fueled by the setting up of hte Indochinese Art Academy by a Frenchman - Victor Tardieu - in 1925.

This fostered new technical skills and vocabulary, shortly to be put to profound uses by thw revolutionary artists in the era 1935-1970.

As the Vietnam Fine Arts Academy says:

“Tardieu rendered great service by laying the foundations for Vietnamese modern Fine Arts“.

Editor: Cao Trong Thiem, “Bao Tang My Thuat Viet Nam”; Vietnam Fine Arts Museum; nd; p.25.

Certainly such a strong Western external art influence was also present in the USSR before the socialist revolution.

It was perhaps somewhat less evident in the Chinese national revolution, or in Albanian art. In China, such influences were transmitted in Shanghai, to artists such as Xu Beihong (1895-1953) who went to the Ecole Nationale Superieur des Beaux Arts in Paris [See Clarke David; Modern Chinese Art’; Hong Kong; 2000; p.18]. And of course Chinese developments in modern art and socialist realism, were spurred on by Lu Xun and his espousal of the wood-cut.

But Western art influence was much more immediately influential in Vietnam.

In Vietnam, the earliest tangible expression of this Western influence realism was by artists such as Le Huy Mien [1873-1943; ‘Making comments on literary work”; 1898] [See Plate 3], and Trang Tran Phenh (‘Phagm Ngu Lao’, 1923).

The former depicts scholars debating merits of literary works, a theme not dissimilar from that of the traditional Chinese inspired Vietnamese artists. But the literature being debated now was slowly becoming more likely to do with modern liberation themes, than of poems on the moon.

Plate 3: Le Huy Mien:

'Making Comments on a Literary Work';

Cao Trong Thiem Ibid; p, 56

While these pioneers utilised the Western medium of oil paints, they restricted their content to local themes, expressed in the highest form of a bourgeois critical realism. By the 1930’s however, the content as well as style, of many painters had become almost identical to the most conventional of the French Impressionist schools such as Renoir. “Little Thuy” (1943) by Tran Van Can (1910-1994) for instance [p.75] [See plate 4], or “Japanese Young Girl” 1942, by Luong Xuan Nhi (1914-) [Plate 5] are clearly overtly influenced by Impressionism.

And this type of content largely came to predominate.

Plate 4: Tran Can Can

'Little Thuy';

Cao Trong Thiem Ibid; p. 74

Plate 5: Luong Xuan Nhi:

'Japanese Young Girl';

Cao Trong Thiem Ibid; p. 77

Residuals of ancient arts were now more found in the mediums used, rather than the contents or subject matter. But if the artists persisted in using the older materials, this had an effect on hte subject choice. So artists attracted to old art forms such as painting on silks, rendered beautiful images of life such as Nguyen Phan Chanh’s [1892-1984] “Going to the Rice Fields” (1937) [See plate 6].

Plate 6: Nguyen Phan Chanh:

'Going to the Rice Fields';

Cao Trong Thiem Ibid; p. 58

With the later revolutionary influences, Nguyen Phan Chanh, persisted in this art form, making such vivid depictions of real life as “Team of Rattan Weavers” (1960) [See plate 7] and “A Good Harvest Meal” (1960) [p. 59].

Plate 7: Nguyen Phan Chanh:

'Going to the Rice Fields';

Cao Trong Thiem Ibid; p. 58

This tradition lasted long into the revolutionary period as the dates show. It also was linked to another tradition, that of wood-cuts which spawned in the revolutionary era, the revolutionary propagandist prints.

Perhaps a specialty of Vietnamese traditional arts was however lacquer painting.

As noted above, statuary and sculpture was often coated in a several layers of lacquer. This is a resin extracted from cuts on the bark of a common Vietnamese tree called ca y son (La: Rhus succedanea), which has is collected in total darkness lest it becomes itself dark (Catherine Noppe & Jean Francois Hubert ‘Art of Vietnam’; New York; 2003). When applied by the artist, it gives a special luster to the painted material – usually a wood – that acts as a vivid light. This light can be burnished with various pigments, into several different colours according to the pigment used, but the most common are golds, reds and greens. Each layer needs sanding down, before a new layer can be added, meaning considerable labour. The quality of lacquer derives from the number of coats, the manner in which the patterns can shine out and the expertise of sanding of the surface, which allows under layers to appear as a bas- relief.

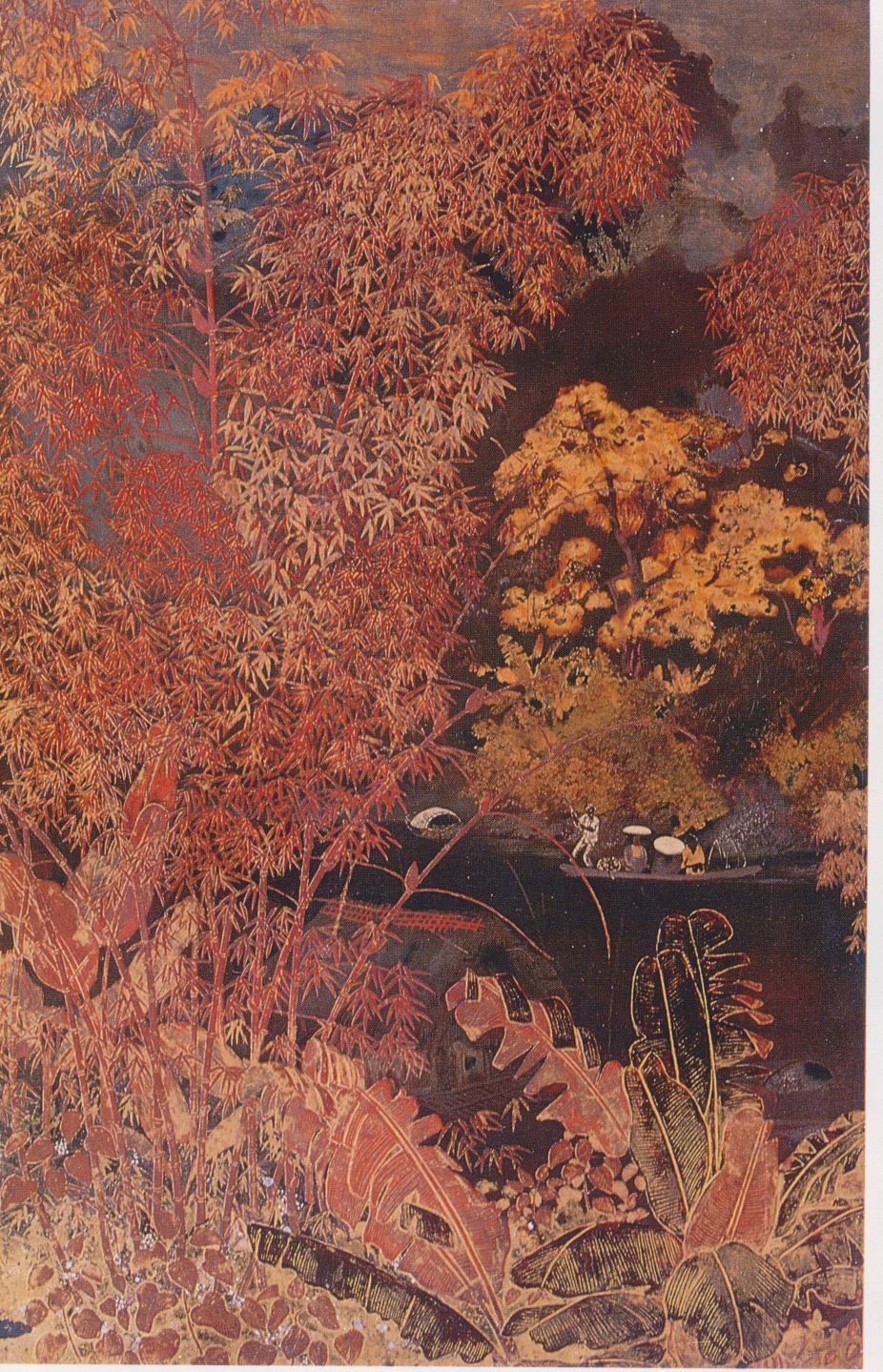

An early exponent of the fusion of traditional form with more modern content was Nguyen Gia Tria (1908-1993).

His screen “In the Garden”, consists of 8 panels that show on one side a profusion of stylised banana and palm leaves. The obverse, consistent with the genre of French painting influences discussed, has a series of pretty, languid women redolent of Impressionist male fantasies. It is undoubtedly striking, but remains a purely decorative piece. Perhaps his ‘Clumps of bamboo in the countryside (1939) shows him at both his technical and content best, showing the florid jungle surrounding peasant on a boat passage [Plate 8].

Plate 8: Nguyen Gia Tria:

'Clumps of Bamboo in the Countryside';

Cao Trong Thiem Ibid; p. 86

That Nguyen Gia Tria wished to be linked to a more nationalist stream is evident since he professed that he:“wished to drop his art studies as he felt all his teachers should be Viertnamese. Tardiese persuaded him to stay”;

Noppe & Hubert Ibid; p. 208.

Artistic Currents during the anti-imperialist struggles.

It was onto this background, that the experiences of the anti-colonial liberation struggle led a new generation of artists into uncharted areas. Influenced by a stream of aesthetic thought from bourgeois liberalism through to socialist realism, they were largely solidly realist. Many of the artists of the Fine Arts Academy decamped, and taught at “Jungle Schools”:

“The first wave of national opposition against the French rule between 1946 and 1954 attracted a good number of Hanoi Fine Arts graduates who went and taught at the “Jungle School” in Viet Bac. . A natural consequence of the shutdown in the wake of the Japanese crackdown on March 31 1954. Out in the jungle you could still sense the war, but you also felt the power of nature and the cultural wealth of ethnic minorities.”Impressively stirring content was drawn from the Indochinese liberation struggles, and often was grafted onto traditional forms, primarily of lacquer.

Noppe & Hubert Ibid; p.212-3

The results are far from simple propagandist art.

Marxist-Leninist aesthetics point out that realist content material, is the most effective art to stir the masses.

Too little attention has been paid to the differences between good realist art, and simple propaganda. Marxist-Leninists have long held that the best art both moves people, but is not ‘tendentious’, in the words of Engels. Alliance has empasised the distinction between “propagandist art”, “state sponsored art”, and the best of socialist art (Memorial to Bill Bland - see Table of Contents Alliance 53).

Much of the best of the art stemming from the Vietnamese national liberation struggle is by any standard, a high art.

Clearly tensions of style remained, and a degree of abstractionism was not uncommon, with some abstract paintings throughout the revolutionary era.

But there is little doubt that the predominant weight of paintings over the period from 1945 to the 1980’s, was realist in content.

Naturally the turns of the long war led to their own effects on the artistic climate. Hence the victory of the national liberation struggle at Dien Ben Phu decisively turned mere pastiches of French impressionists into an expression of un-welcome and hostile anti-patriotism.

Sections of the intelligentsia and artists were unwilling to contemplate any further struggle, and any possible move into socialism; and became disillusioned.

As a hostile art history by Noppe and Hubert puts it, the battle of Dien Bien Phu marked a turning point:. It was here that the Vietnamese decisively defeated French imperialism, led by General Giap and Ho Chi Minh. Some artists chose Western abstractionism at this stage:

“Yet if artists (in the Jungle Academy –ed) were first and foremost observers, they were also fighters in an unequal struggle. Within a handful of years patriotic fervour gave way to disenchantment. Bui Xuan Phai was among the first who went back to the city in 1952”.

Noppe & Hubert; Ibid; p. 212.

“A radical change of situation came with the crushing defeat of the French at Dien Bien Phu in May 1954… From then on socialist realism became an imperative.. painters who had joined independent fighters from 1946 and depicted courageous and unpretentious freedom fighters enjoyed the full support of the rural population, suddenly found them gagged by socialist realism only a decade later. Such as Bui Xuan Phoi, Duong Bich Lien, Nguyen Sang, and Nguyen Tu Nghien”.It is not surprising that an Art Forum was established that expressed the aspirations of national liberation, and expected its’ artists to assist in this expression.

Noppe & Hubert Ibid; p. 113.

It is equally un-surprising that the overt failure of the revolution to move to the socialist path, or the second stage of the Leninist revolution, would lead to the firm and ever stronger enthronement of capital. This was established openly by the so-called Doi-Moi reforms (See Alliance 27: On Ho Chi Minh and Vietnamese Revisionism – at http://www.allianceML.com/China/ALLIANCE27HOCHIMINH.htm).

These developments led to a resurgence of abstractionism and vague, moody Vietnamese beautiful ladies in art:

“The Art forum set up headed by Thai Ba Van set the baseline for modern art.. and helped stifle artistic expression, although doi-moi reforms introduced a certain amount of leeway of 1985… All Vietnamese artists felt the burden of censorship”.

Noppe & Hubert; Ibid; p. 219.

Examples of Works in the National Liberation Struggle

To see the currents at play, we should examine the paintings over this period.

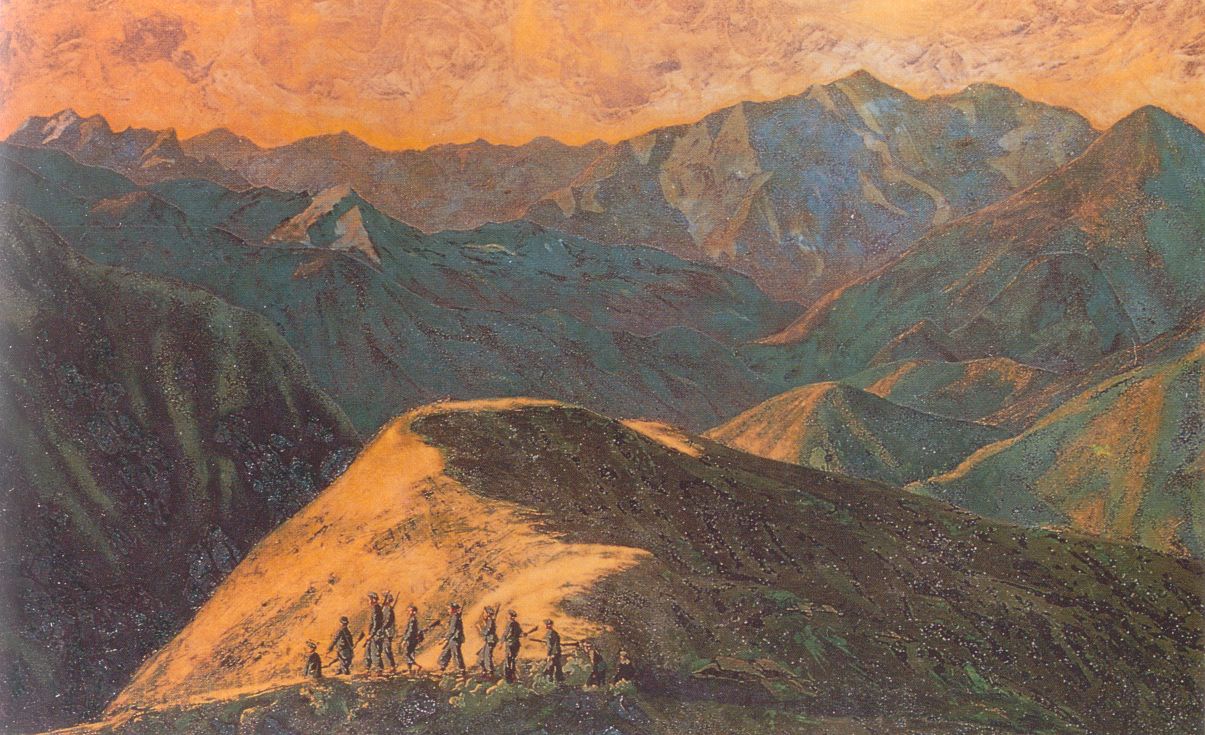

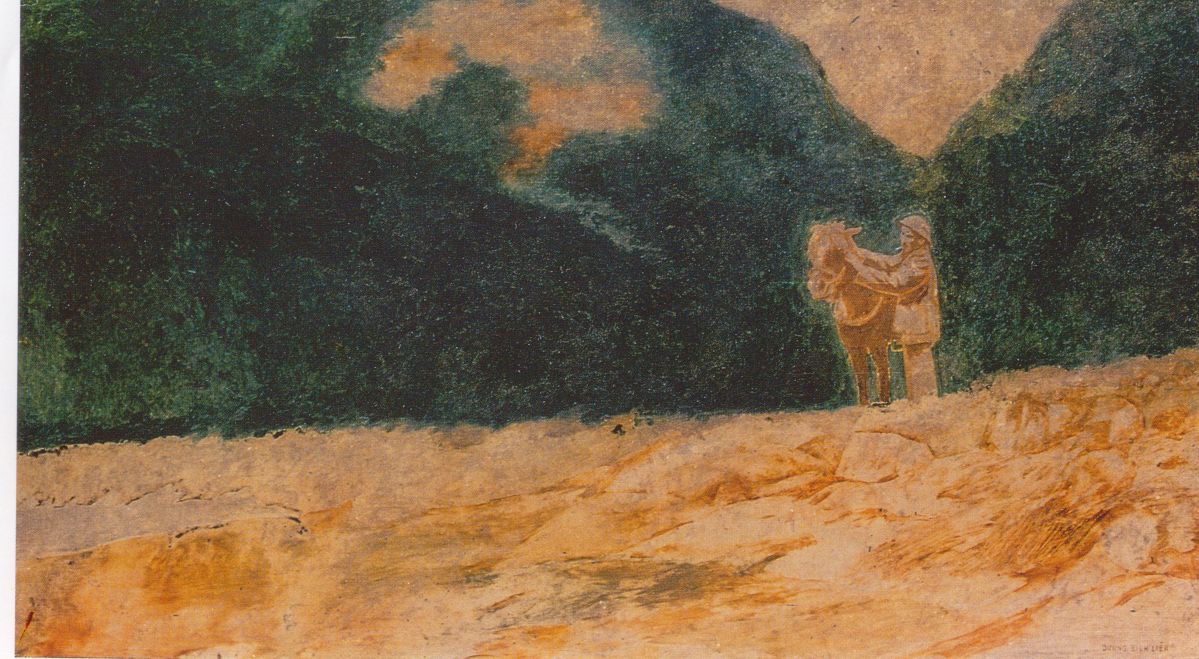

In the make-over of traditional forms, some of the lacquer work is very striking. See for example “Recalling One Afternoon in Tay Bac” 1922, by Phan Ke An (b 1923). [Plate 9] see p.103.Beautiful sun burnished green mountains form a background to a small troop of soldiers crossing a ridge. Here both content and form are perfectly matched. The ‘everyday’ aspect of a troop of soldiers is part of the scenery.

Plate 9: Phan Ke An:

'Recalling One Fine afternoon in Tay Bac';

Cao Trong Thiem Ibid; p. 103

In “Ham Rong Bridge”(1976) by Tran Oanh (b.1937) [Plate 10], workers are shown against an impressive background of the river in brilliant reds and golds.

Plate 10: Tranh Oanh

'Ham Rong Bridge';

Unpublished Source.

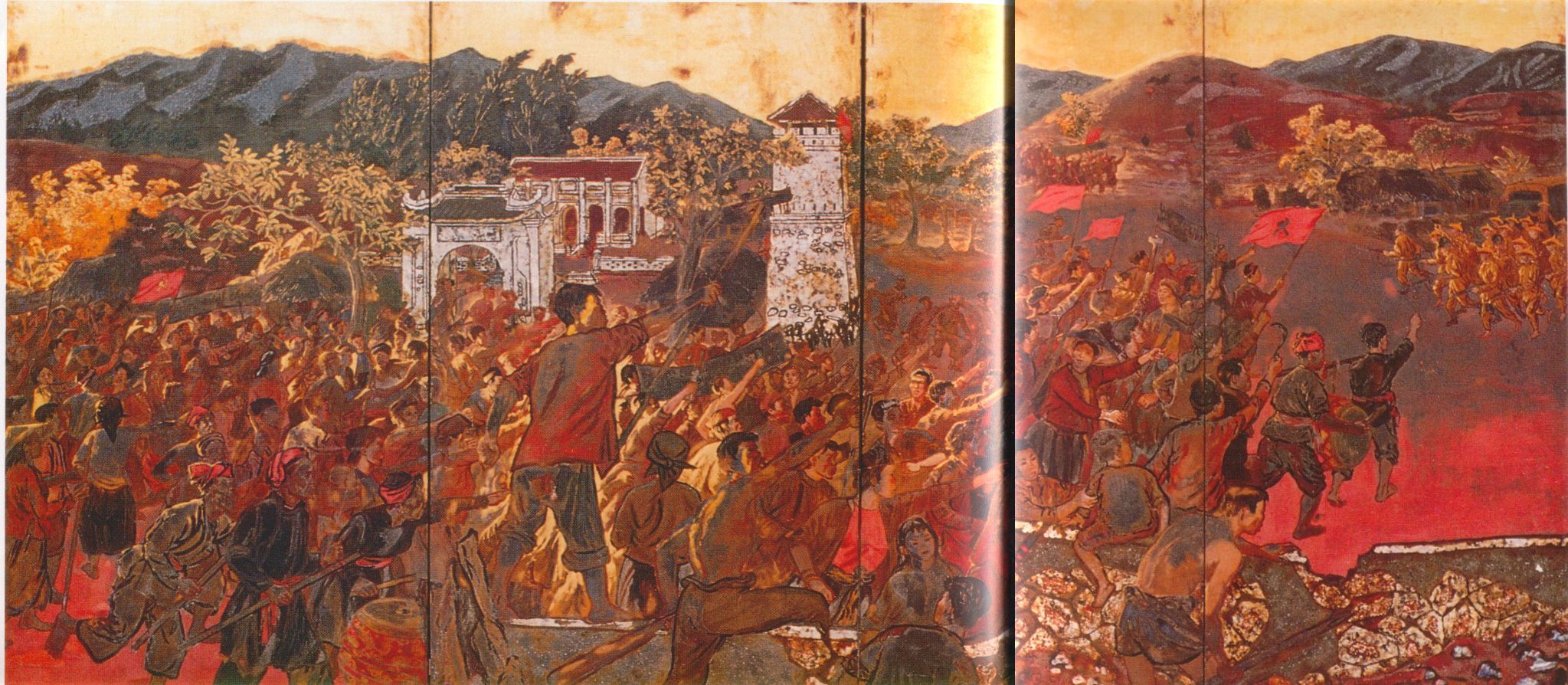

There is little doubt that the use of such heavy reds in this late painting, is an allegory for socialism. This use of the red and gold lacquer is made even more explicit in such paintings as the large and impressive 4 panels of the “The Nghe Tinh Soviet” of 1958 by six painters led by Nguyen Duc Nung [Plate 11].

Plate 11: Nguyen Dic Nung, Tran Dinh Tho, Pham Van Don, Nguyen Van Ty, Huynh Van Thuan, Nguyen Sy Ngoc:

"Soviet in the Provinces of Nghe An and Ha Tinh"

Cao Trong Thiem Ibid; p.109

Even some of the abstractionist elements during this

period, are sometimes very powerful. Such as for example “From Darkness

(1982) by Le Quoc Loc (1918-1987) [Plate 12] (p.102). Surrounding blocks

of black and gold shapes of lacquer, depict houses in the night. In one off-centre

house, placed high on the wood surface, a gold and red light brightly lights

a central room. The red light is the hammer and sickle on one flag, with

a second flag composed of a gold five-pointed star on a red background.

In front of them are black silhouettes of men and women workers saluting

the flag.

Plate 12: Le Quoc Loc

"From Darkness" ;

Cao Trong Thiem Ibid; p.109

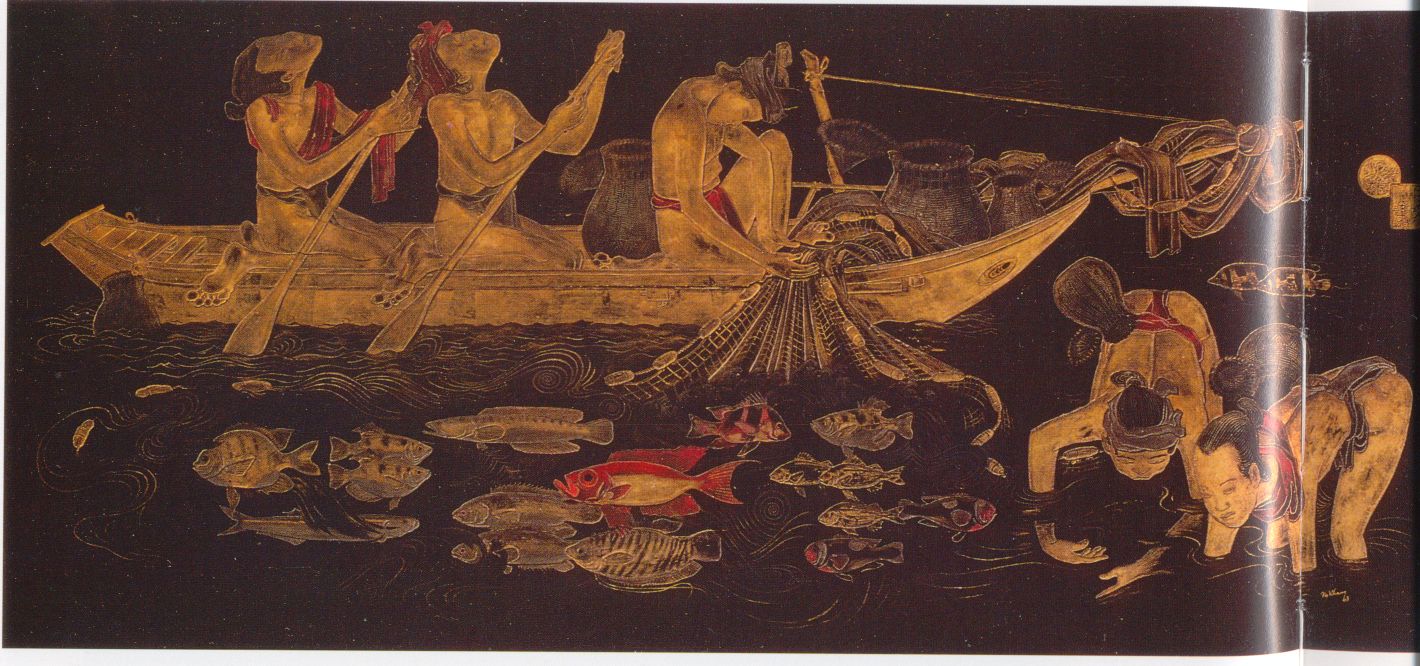

Plate 13:

Nguyen Khang; "Fishing in the Moonlight";

Cao Trong Thiem; Ibid; p. 60

This type of artistic tradition continued well into the 1980’s. Nguyen Khang (1912-1989), who we met above, in 1960 did the 3 panel painting “Troops Marching Across a Stream”, in the same impressive lacquer tradition as he had used in 1943 [Plate 14]. At an initial look, all one sees is a dense jungle with groves of bamboo and green profusions. Then one sees that the jungle truly is alive, that the Viet Cong are moving silently across it and fording a stream.

Plate 14: Nguyen Khang; "Troops Marching Across a Stream";

Unpublished Source

It should not be thought that the materials were confined

to lacquer. Oil was also very commonly used. For instance, depicting the

road that Vietnam had come through, Huynh Van Gah (1922-1987) showed a harrowing

line of Vietnamese refugee prisoners who are being foot-marched by French

colonial guards [Plate 15].

Plate 15: Hyunh Van Gah

'Prisoners';

Unpublished Source

In contrast Nguyen Trong Kiem (1930-1991) composed a haunting allegory of the future - “When a Child was Born” (1960); [Plate 16]. This large painting depicts a newborn child in the arms of its mother, with an army father standing close. All around are the people, evidently poor, against a background of a bombed out city. The meaning is clear, that the new state will provide a new society.

Plate 16: Nguyen Trong Kiem

'When a Child Was Born';

Cao Trong Thiem Ibid; p. 133

While all these examples of art vary in their degree

of “tendentiousness”, little that we have illustrated can be really termed

hagiographic. That is not to say that there are a considerable number

of images of Ho Chi Minh. Many of these are of Ho in ordinary activities,

or in the guerrilla camps, of “Uncle Ho on a Mission in Viet Bac” by Duong

Bich Lien (1980) [Plate 17].

Plate 17: Duong Bich Lien;

'Uncle Ho On a Mission in Viet Bac';

Cao Trong Thiem Ibid; p. 124

While these images certainly exist, the predominant feel obtained from

the paintings exhibited in the Vietnam Museum of Arts is of a far broader

and higher art activity than can be classified as ‘propaganda’ art or hagiographic

art. Rather impressive technical and visually appealing pictures of real and

ordinary people are far more predominant.

War Themes

Not even

a simple overview as this, of the artistic legacy of modern Vietnam should

ignore the war themes. These are in such abundance, that for instance at

the War Museum Hanoi, many are not even given the honour of a label illustrating

the title or the artist. A selection of these can be found relatively easily,

in a publication from the British Musuem of late war drawings, in "Vietnam

- Behind the Lines - Images from the War 1965-1975"; Jessica Harrison-Hall;

London 2002.

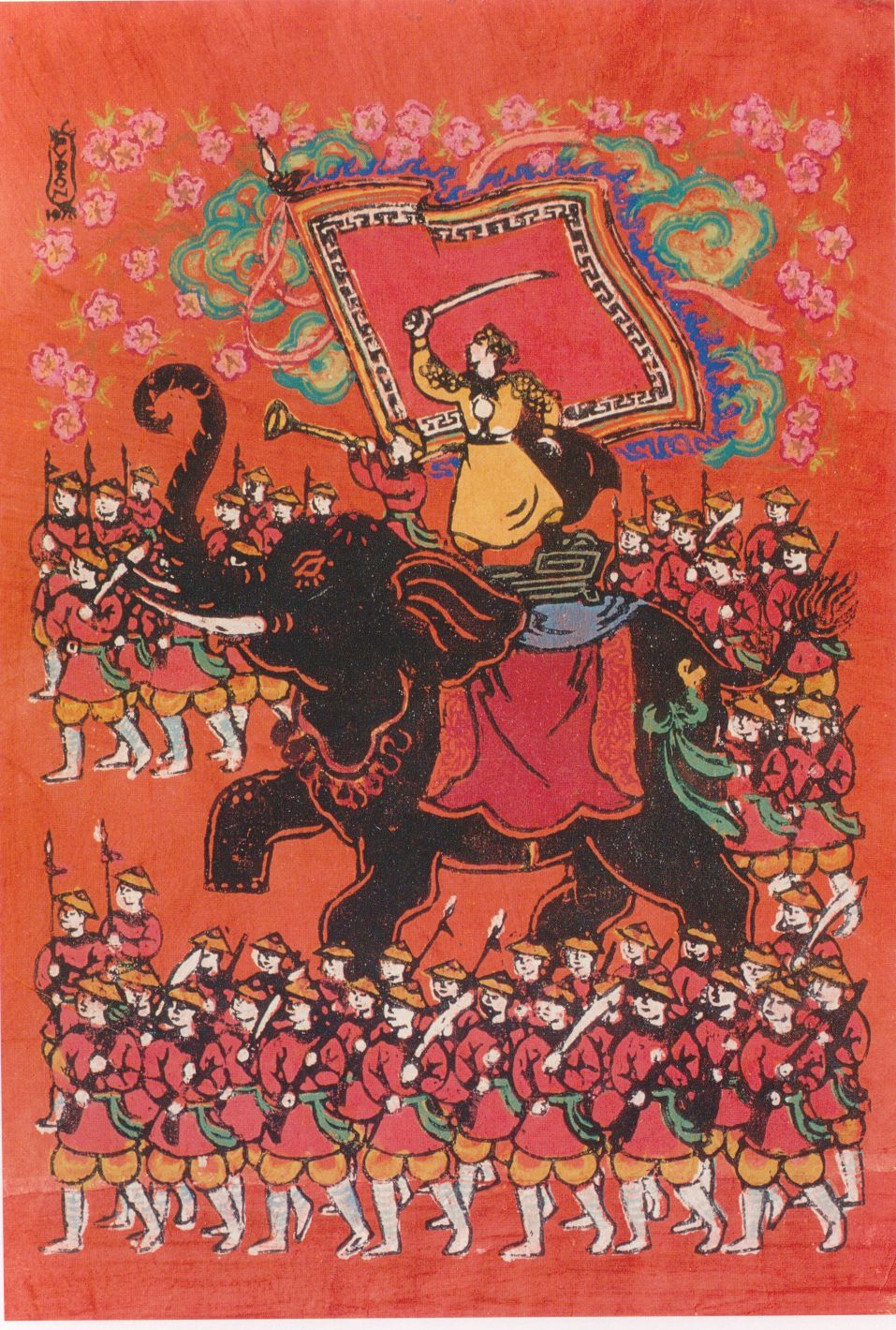

This article will not discuss poster art in any detail. But an interesting

historical comparison of the wood cut in Plate 3, shows again how the modern

Vietnamese artist harked back to her/his heritage at a number of points.

The wood cuts continue the famous Da Hong village traditions. They both

depict episodes from earlier wars of national liberation, in particular

those against the Chinese Han dynasty who occupied Vietnam for many years.

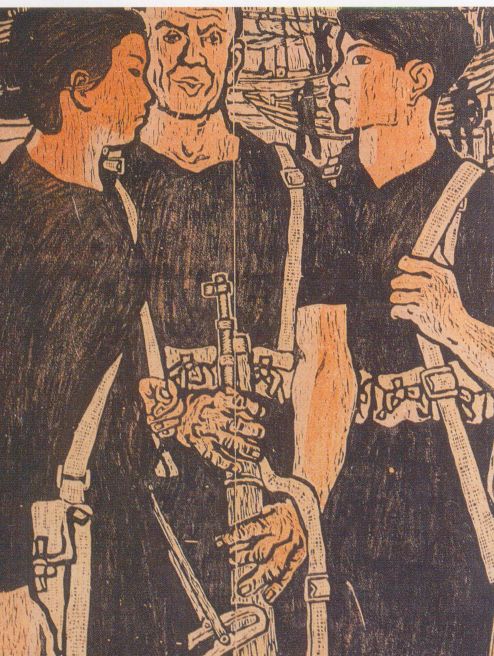

Plate 17: Pham Van Don; Plate 18: Hoang Tram; 'Three Generations'; Cao Trong Thiem Ibid p.121;

Cao Trong Thiem Ibid; p.98

The sheer plethora of art produced regarding the war cannot be quickly

précised in a short article, and these examples from the War Museum should

suffice. But three pictures from the Fine Arts Museum are worth showing

with a little discussion also. So these again revert to the fine arts tradition

of using lacquer, and again do so in an ingenious manner.

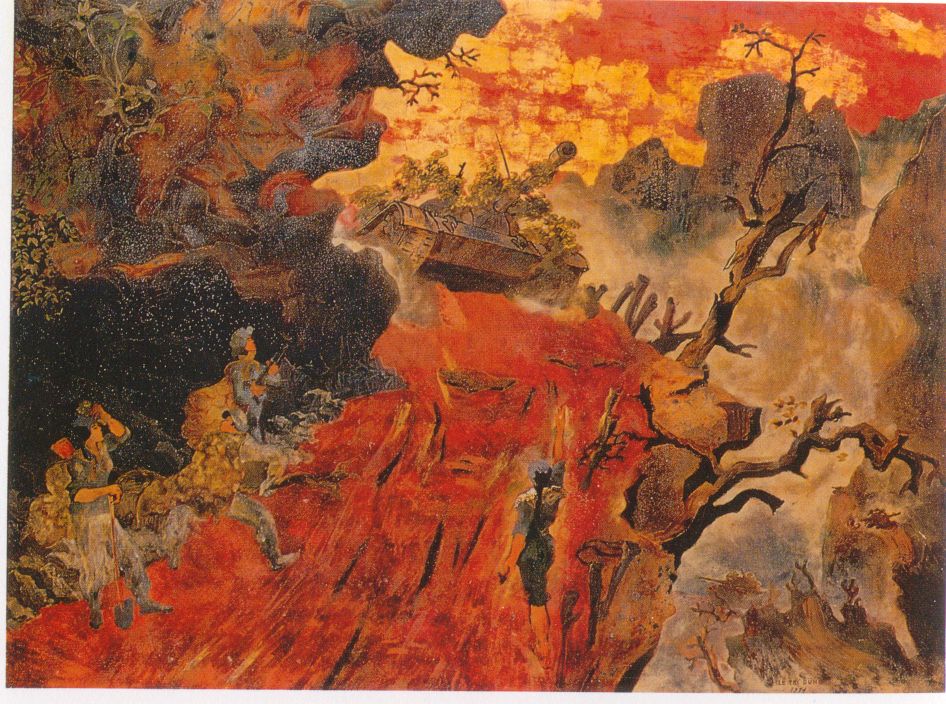

Le Tri Duong (1949) painted “Breaking Through a Key Point”

showing a tank with its barrel aiming at the skies, bursting through a blockade

onto a red road, being hailed by 4 guerillas – three women and a man. The

red lacquered road and the gold lacquered background are again symbolic.

[Plate 19].

Plate 19:

Le Tri Duong; “Breaking Through a Key Point

Cao Trong Thiem; p.170.

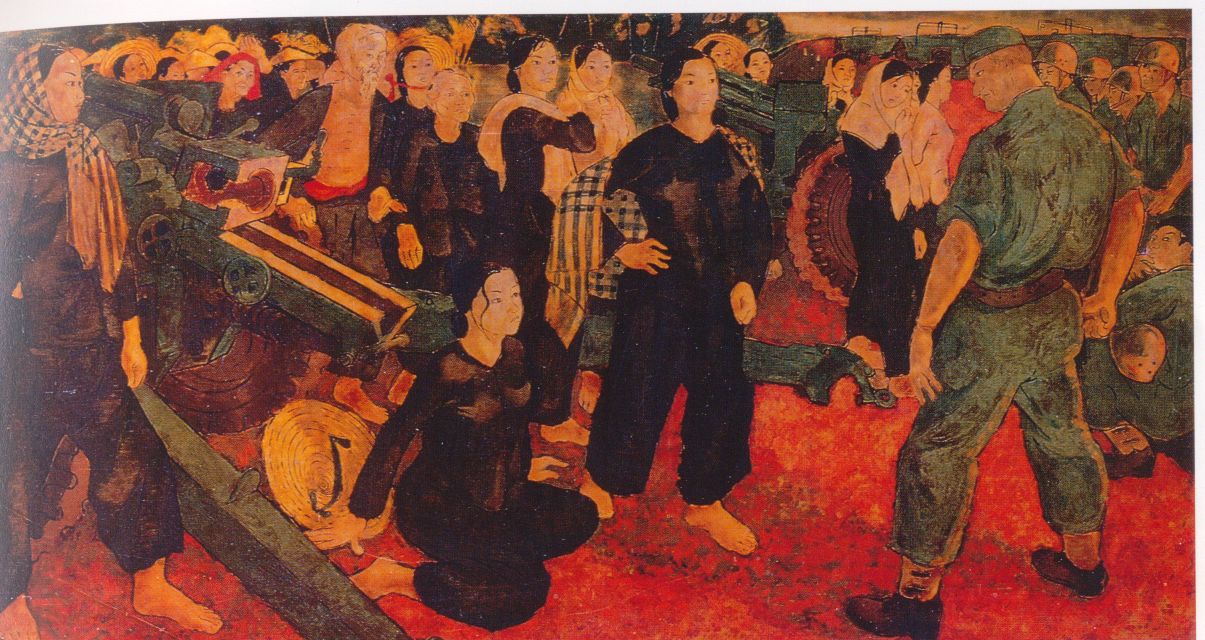

Hyunh Van Gah, who we met above, in “Heat and Gun” shows

an impressive confrontation between a phalanx of black-pajama-ed women and

one old man and a US marine.

Plate 20: Hyunh Van Gah; "Heart & Gun":

Cao Trong Thiem Ibid p.123;

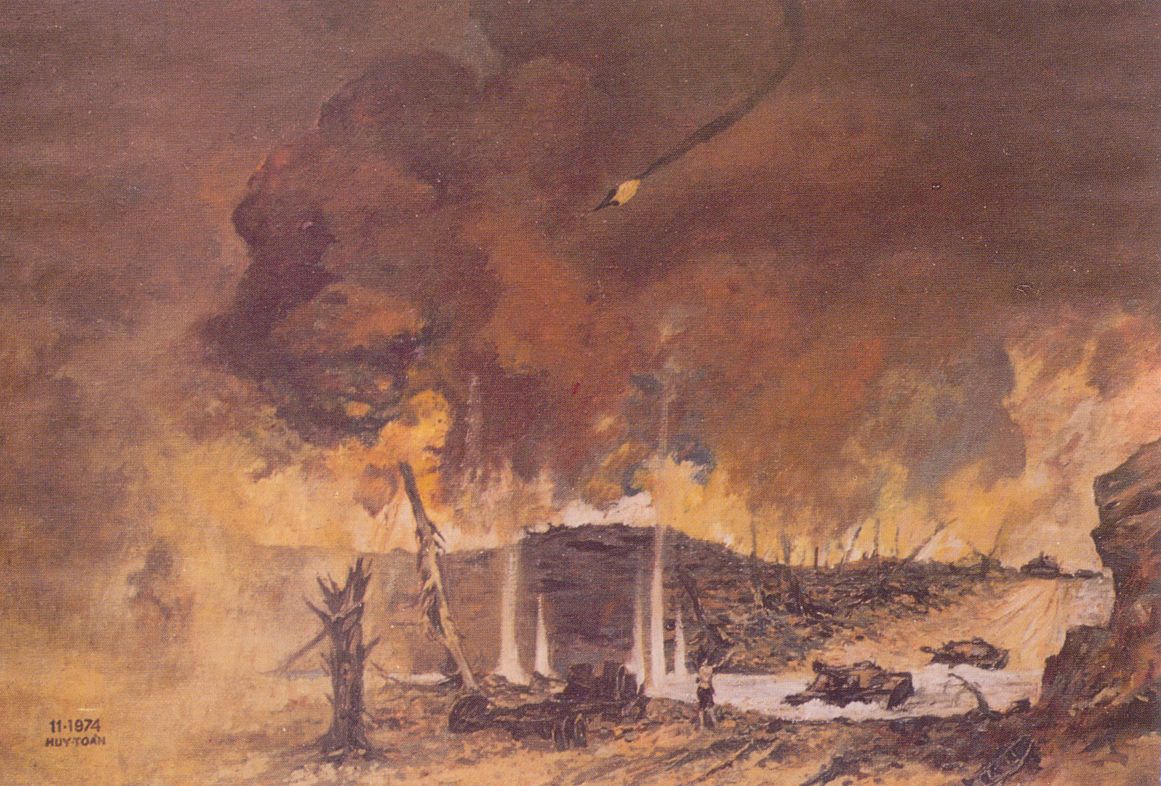

In ‘Fire Coordination’, (1974) Le Huy Toan (born 1930) painted in 1974, shows a bleak and frightening landscape composed of bomb craters and shrapnel cascades into the sky, while a single young girl confronts a series of tanks approaching her.

Plate 21:

Le Huy Toan; "Fire Coordination'; Cao Trong Thiem Ibid; p.136

Aftermath of Doi Moi – Faceless Women and Western Reproductions

While the national liberation struggle was victorious, it was never moved beyond that to the socialist phase. The “Chinese” wall identified by Lenin between the two revolutions – firstly the national democratic liberation, and secondly the socialist revolution - was never breached in Vietnam. That Ho Chi Minh was an inspiring and great leader of the Vietnamese peoples, is beyond doubt. However his legacy is largely that of a great national liberation ideologist.

After Ho Chi Minh’s death, and the final liberation of the South of Vietnam, the state erected in Vietnam was controlled by the Vietnamese national bourgeoisie. However within a relatively short space of time, the state was once more marked by an enormous influx of foreign capital. The policy of “Doi Moi” made this quite official. That this influx of foreign capital, was both unlimited, and not without burdens on the Vietnamese people is evident. Unsurprisingly USA capital is not very high on the score sheet, being much lower than Singaporean, Taiwanese, Korean and Japanese capital. Irrespective of which capital inflow is dominant, the net result has been the open and unequivocal development of capitalism in an acknowledged “open market” economy. The result on art has been frankly paralleled. Pictures of languid Vietnamese women, often faceless and often dressed (if not un-dressed) in the now ‘traditional’ white ---, abound. Interestingly the market place is full of the heirs of the technically proficient artists of the earlier period. They are now largely reduced to selling the most elaborate reproductions of any Western artist that takes your fancy. From Dali to Picasso to Renoir to Van Goh – all are perfectly reproduced in oils and available at a fraction of what it might cost in the West, were it possible to get such.

CONCLUSIONS

Naturally, there are far more pressing concerns for the Vietnamese peoples than their art history.

Many still live in an astounding poverty.

Despite national liberation, life is hard for the Vietnamese peasants, numbering still about 75% of the population. Official figures for unemployment are around 7-10%. Degrees of disparity between rich and poor are growing rapidly, as even officials of the World Bank have recognised, citing growing ginni coefficients for Vietnam.

Vietnam’s art history however, is another affirmation of the Marxist aesthetic viewpoint, that art reflects the society in which it develops. We believe it also shows that the socialist realist tradition – as it was embraced by the Vietnamese liberation artists – is much deeper than simple hagiography. At its’ best, and why should an artist not strive for her or his best? – it is an affirmation of life, and a philosophic reflection upon all of life.

Afterword

We apologise for the poor quality of a few of the pictures.