REVISIONIST ECONOMICS IN THE USSR

Alliance

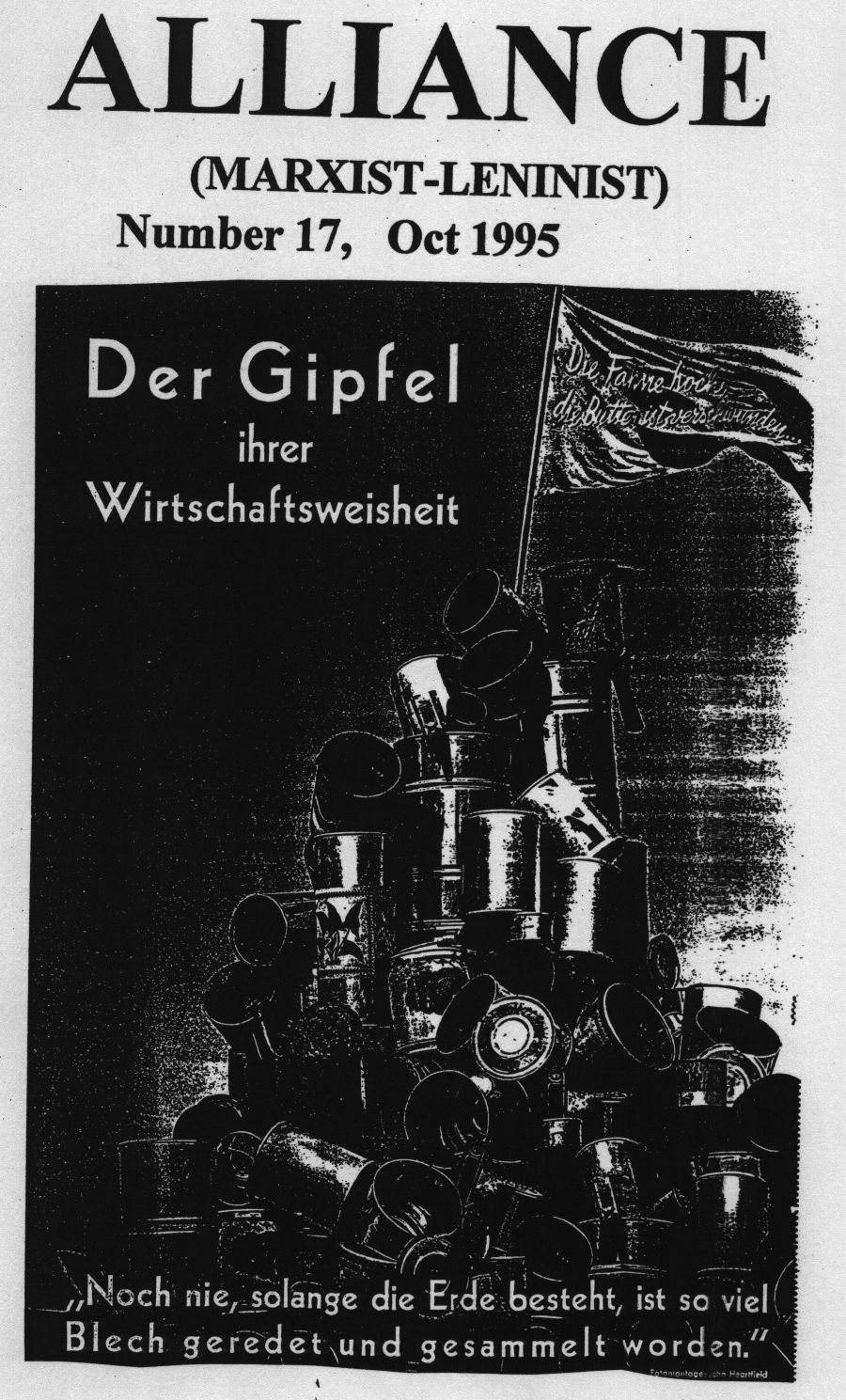

4, reprinted

some pioneering photomontges of JOHN

HEARTFIELD (1891-1968). This

is another example.

Originally Helmut Herzfeld, this artist put his

talents to aid the world's working class.

Under German fascism, he deliberately

adopted an English name. He worked as a member, for

the German Communist Party.

His hard hitting satires drove home the messages to German

workers; that

fascism and Hitler was their worst enemy.

This 1937 poster is entitled

"The Pinnacle

of their economic wisdom".

On the flag is

written:

"Raise

the

flag, the butter has disappeared".

At the bottom

of the empty

tin cans is written:

"Never since this world

existed has so much empty talk

been spewed out and collected".

AS MUCH CAN BE SAID OF REVISIONIST AND BOURGEOIS ECONOMIC THEORY.

EDITOR'S INTRODUCTION

This

issue of Alliance North America concerns revisionist economics.

Economics is

often a

confusing topic. But Marxist-Leninists need to understand some of the

technicalities.

Why? Because the bourgeoisie uses technical "froth"

to disguise the essential fact - exploitation.

In the USSR, this disguise, was aimed

at undermining Marxist economics with revisionist theories.

After

Stalin's death, it succeeded.

Previously

Alliance has

discussed both modern day economic

issues (See Alliance 3 on

inflation versus deflation; and protectionism etc); and economic

revisionism.

The relation of economic revisionism to the confusion following

the death of Stalin, has been e

xtensively discussed in Alliance.

Comrade

Bland (Communist League - UK) showed,

that the economic measures proposed and enacted

by Khrushchev, were first

proposed by Vosnesenky and defeated by Stalin

(See Alliance Number 9 :

reprint `The Leningrad Affair').

Stalin

correctly foresaw that the

implementation of these proposals would lead straight to

capitalism.

Hence the

title of Bland's book : "The Restoration

Of Capitalism In

the USSR"

(See reprint Alliance 14).

In

order to further understand how revisionism spread its

tentacles - we re-print some work of

the Marxist-Leninist Research

Bureau (UK), published

in 1995. This details the rise of

revisionist

economics in the USSR.

The two revisionists analysed here, are EVGENY

VARGA and NIKOLAY

VOSNESENSKY.

The latter has been remarked upon in Alliance before,

but this report carries more detail.

Finally we make a brief

announcement.

Shortly we will be

publishing an "Open

Letter"; that deals with some current confusion about

the pseudo-Left

revisionism of Mao Ze Dong.

Please note:

The designation * by a name, signifies that Bland has written a

short biographical

not,to be found at the end of the article.

Biographical

Note (to 1949)

Nikolay

Akekaeyevich Voznesensky* became the principal defendant in what later

became

known in the Soviet Union as 'the Leningrad Affair':

"The term 'Leningrad

Affair' . . . has been used in the Soviet Union since 1954

to

describe a purge that took place in 1949-50 involving a number of Party

and

state officials, most of whom were then or before connected with

Leningrad".

(Adam B. Ulam:

'Stalin: The Man and His Era'; London; 1989; p. 706).

Voznesensky was born in 1903 in

the Tula region (just south of Moscow), and joined the Communist Party

in 1919,

two years after the Revolution. From 1921 to 1924 he studied at the

Sverdlovsk

Communist University, from which he graduated.

Between 1928 and 1934 he was a student, and later an instructor, at

the

Institute of Red Professors. In 1935 he became a Doctor of Economics.

Between

1435 and 1937, he was Chairman of the Leningrad City Planning

Commission.

In December 1937 he was

appointed Deputy Chairman of the USSR State Planning Commission, and in

January

1938 became its Chairman.

On the outbreak of war in 1941, he became a member

of the State Defence Committee, and also a Deputy Prime Minister. In

1943 he

was elected a member of the USSR Academy of Sciences.

After the war, he was engaged

in the rehabilitation of the national economy,

and in 1947 became a member of the Politburo of the Central Committee

of

the CPSU.

The Campaign to Relax Planning

Priority for Means of Production (1945-47)

Nikolay Voznesensky was closely associated with Mikhail

Rodionov*, who was appointed Premier of the Russian Federation (RSFSR)

in 1946.

The two had been

“linked in 1945 by a common approach to practical

economic problems".

(William

O. McCagg, Junior: 'Stalin Embattled: 1943-1948'; Detroit; 1978; p. 134).

The principal feature of this

common approach was the proposal that, now that the war was over, the

traditional priority accorded to means of production in Soviet economic

planning could and. should be relaxed.

In this year, . Voznesensky,

Mikoyan*, Kosygin* and Rodionov came in 1945:

“explicitly together as a

managerial grouping which favoured establishing a place in the

peacetime

economy of the Soviet Union for light. as well as heavy industries. . .

. His

(Voznesnsky's -- Ed.) Five Year Plan speech of March 1946 assigned

priority on

the immediate level to reconstruction tasks, civilian housing nd consumer goods. . . . After 1945 this

group, and particularly Rodionov, was involved in political

intrigues, . . . Rodionov . . . was a Russian nationalist". (William O.

McCagg, Junior: op. cit.;

p. 134, 135).

The group around Voznesensky

used their power base in Leningrad to introduce in the Russian Republic

some of

the policy changes for which they stood by introducing :

" . . . after 1945 . . .

in the Russian Republic a number of administrative reforms to increase

consumer

production. . .

During 1946 and 1947, for

example, the Russian

Republic blossomed with

ministries for technical culture, cinematography, luxury goods,

delicatessen products, light industry and the like".

(William O. McCagg, Junior: op.

cit.; p. 135, 363).

The

Soviet-German Joint Stock Companies (1945-47)

About this time,

" . .

. Voznesensky and Mikoyan . . . set up

joint

Soviet-German stock companies and assigned to them huge

industrial

assets".

(William O. McCagg, Junior: op. cit.; p. 137).

In 1947, the Marxist-Leninists:

" . . . counter-attacked,

and gradually the Voznesenskys and Mikoyans were compelled to hand over

their

joint stock companies to the German Communists".

(William O.

McCagg, Junior:

op. cit.; p. 137).

Relations with the Yugoslav

Revisionists

(1946-48)

Between 1946 and 1948, leading Leningrad figures

established friendly

contacts with Yugoslav leaders who were, in the latter year, denounced

by the

Cominform as revisionists. Milovan Djilas* describes how Aleksandr

Voznesensky*, Nikolay's elder brother, expressed revisionist

views

to him in 1946:

"I was well

acquainted with Voznesensky's elder brother, a university

professor

who had just been named Minister of Education in the Russian

Federation. I had

some very interesting discussions with the elder Vosnesensky at the

time of the

Pan-Slavic Congress in Belgrade in the winter of 1946. We had agreed not only about the

narrowness and bias of the

prevailing theories of 'socialist realism', but also about the

appearance of

new phenomena in socialism . . . with the creation of the new socialist

countries and with changes in capitalism which had not yet been

discussed

theoretically".

(Milovan Djilas: 'Conversations

with Stalin'; Harmondsworth; 1963; p. 117).

Djilas reports that a Yugoslav

delegation to the Soviet Union in January 1948 was received in Moscow

with

'reserve', but was warmly welcomed in Leningrad. He tells us that since

the

delegation

“. wished to see Leningrad .I approached Zhdanov* about this, and he graciously agreed. But I also noticed a certain reserve. .

Our encounter with Leningrad's officials added human warmth to our admiration. . . . We got along well with them, easily and quickly. . . . We observed that these men approached the life of their city and citizens -- that most cultured and most industrialised centre in the vast Russian lend -- in a simpler and more human way than the officials in Moscow.

It seemed to me that I could very quickly arrive at a common political language with these people simply by employing the language of humanity".

(Milovan Djilas: ibid.; p. 129, 130-31).

"In January 1948, shortly before relations between Moscow and Belgrade were broken off, a Yugoslav delegation headed by Djilas arrived in the Soviet Union. They were coolly received in Moscow, but very cordially in Leningrad".

(Boris Levytsky: 'The Uses of Terror: The Soviet Secret Service: 1917-1970'; London; 1971; p. 193).

Vladimir Dedijer*,too, confirms that the Yugoslav delegation

“. . . expressed a wish to visit Leningrad. They were warmly welcomed there".

(Vladimir Dedijer. 'Tito Speaks: His Self-portrait and Struggle with Stalin'; London; 1953; p. 322).

Naturally, these developments did not go unnoticed in Moscow. The Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party noted in its letter to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia of 4 May 1948 that the last Yugoslav Party delegation to the Soviet Union had preferred to obtain 'data' from officials of the local Leningrad organisation than from officials in Moscow:

"It should be noted that the Yugoslav comrades who come to Moscow as a rule travel quite freely about and around the towns of the USSR, that they meet' our people and talk freely with them. . . . At the occasion of his last visit to the USSR, Comrade Djilas, while sojourning in Moscow, went for a couple of days to Leningrad, where he talked with Soviet comrades. . . . Comrade Djilas has abstained from collecting data from . officials of the USSR, but he did so with local officials in Leningrad organisations.

What did Comrade Djilas do there, what data did he collect? We have not considered it necessary to busy ourselves with such queries. We suppose he has not collected data there for the Anglo-American or the French Intelligence Services".

(Central Committee, All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks): Letter to CC, CPY, 4 May 1948, in: 'Correspondence of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia and the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks)'; Belgrade; 1948; p. 52).

In this connection, Robert Conquest* points out:

"Thus the Leningraders are said to have given Djilas material which would have been harmful to that State if handed over to imperialist secret services.

But within a year it was said that the Yugoslays were agents of the secret services".

(Robert Conquest: 'Power and Policy in the USSR: The Study of Soviet Dynastics'; London; 1961; p. 102).

The 'Cult

of

Leningrad (1947-48)

In 1947,

. . . M. I. Rodionov, the young Russian nationalist leader, . . . publicly linked his campaign for reform in the Russian Republic with the cult of Leningrad".

(William O. McCagg, Junior: op. cit.; p. 275).

As a part of this campaign, in 1948 the group around Voznesenky proposed that the the capital of the Russian Republic be moved from Moscow to Leningrad, a proposal which came to be a central feature of the 'Leningrad Affair'. They proposed

“..that the capital of the Russian Republic be transferred from Moscow to Leningrad, and that the republic's Party headquarters be moved to the northern city as well. The advocates of that move were Rodionov and Vlasov, respectively chairmen of the Council of Ministers (Prime Minister -- Ed.) and of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet (President --Ed.) of the RSFSR".

(Pater Deriabin: 'Watchdogs of Terror: Russian Bodyguards from the Tsars to the Commissars'; Bethesda (USA); 1984; p. 312).

In 1948 Pyotr Popkov*, First Secretary of both the Leningrad Regional and City Committees of the Party, proposed to Nikolay Voznesensky

“. . . that he should 'patronise' (i.e., pay special attention satisfying the needs of -- Ed.) Leningrad".

('Political Archives of the Soviet Union', Volume 1, No. 2 (1990) (hereafter listed as 'Political Archives (1990)'; p. 154).

Voznesensky did not inform the Central Committee of Popkov's approach.

The Soviet

Marxist-Leninists

saw these proposals as a move to make the Communist Party in the

Russian

Republic the centre of an anti-Party, anti‑

socialist conspiracy.

Voznesensky's

Book 'War Economy of the USSR . . .' (1947)

In 1947 a major work by Voznesensky was published. It was entitled 'Voyennaia ekonomika SSR v period otechestvennoi voini' (The (War Economy of he USSR in the Period of the Patriotic War'). An English translation was published in 1948.

The book incorporated a number of theses diverging from long-accepted Marxist-Leninist principles, namely:

1) it favoured a relaxation of the principle that Soviet economic planning should give priority to the production of means of production:

For example, the chapter headed 'Post-War Socialist Economy' proposes :

“. . . the increase of the portion of the social product earmarked for consumption".

(Nikolay Voznesensky: 'War Economy of the USSR in the Period of the Patriotic War'; Moscow; 1948; p. 147).

Robert Conquest points out that

“the practical application of Voznesensky's view might be an increase in consumer goods rather than in industrialisation".

(Robert Conquest: op. cit.; p. 111).

2)

it

favoured the concept that the state planning authorities should base

the

distribution of production resources in the economy on the law of

value:

"The state plan in the Soviet economic system makes use of the law of value to set the necessary proportions in the production and distribution of social labour and the social product. . .. The law of value operates . . . in the distribution of labour among the various branches of the Soviet Union's national economy. The state plan makes use of the law of value to ensure the proper apportionment of social labour among the various branches of the economy". (Nikolay Voznesensky: op. cit.; 117, 118).

Economist Janice Giffen comments:

"N. A. Voznesensky . . . had attempted to give greater significance to the law of value in the Soviet economy" .

(Janice Giffen: 'The Allocation of Investment in the Soviet Union: Criteria for the Efficiency of Investment', in: Peter J. D. Wiles (Ed.): 'The Soviet Economy on the Brink of Reform: Essays in Honour of Alec Novas; Winchester {USA): 1988; p. 56).

3)

it

presented the state economic plan as the equivalent of an economic

law:

"It

is essential to note the . . . specific features of

the state economic plan that convert it into the law of economic

development in

the USSR.

. . . The state plan

has the force of a law of economic development, because it is based on

the

authority and practice of the entire Soviet people organised into the

state. .

. .

Socialist planning . . . is in itself a special law of development and as such a subject of political economy".

(Nikolay Voznesensky: op. cit.; p. 115, 120).

The New Zealand-born economist Ronald Meek* points out that Voznesensky's theory

“ . comes very close indeed to a virtual identification of 'economic law' under socialism with government economic policy". (Ronald L. Meek: 'Studies in the Labour Theory of Value'; London; 1956; p. 273).

and the American economist William O. McCagg, Junior*, comments:

"It was basic to Voznesensky's argument that miracles were possible because the system was socialist".

(William O. McCagg, Junior: op. cit.; p. 142).

That Stalin was opposed to Voznesensky's views, which he condemned as a programme 'to restore capitalism', was admitted by Khrushchev in Sofia in June 1955:

"According to Khrushchev*, Voznesensky (shortly before the Leningrad purge) . . . . went to Khrushchev*, Malenkov and Molotov and said that he had spent a long session with Stalin explaining his draft for the new Five-Year Plan. Part of this provided for some relaxation of .planning and for certain NEP-style measures. . . . Stalin had then said: 'You are seeking to restore capitalism in Russia".

(Wolfgang Leonhard: 'The Kremlin since Stalin'; London; 1962; p. 177).

"Voznesensky expressed views differing from Stalin's on questions of economic policy".

(Boris Levytsky: op. cit.; p. 192).

Nevertheless, initially the book was widely praised in the Soviet press, and was awarded a Stalin Prize in 1948.

Stalin was made aware that Voznesenky's theories had the backing of Khrushchev* and other leading Party members:

"Voznesensky is said . . .to have asked Khrushchev and others to intercede with Stalin . . . . These colleagues were granted an intrerview with Stalin and expressed support for some of Voznesensky's measures".

(Bruce J., McFarlane: 'The Soviet Rehabilitation of N. A. Voznesensy --Economist and Planner', in: 'Australian Outlook', Volume 18, No. 2 (August 1964); p. 152).

The Australian economist Bruce McFarlane* points out that Voznesensky's economic theories anticipated the economic changes introduced by the Soviet revisionists after Stalin's death:

"His (Voznesensky's — Ed.) economic theories . . . anticipated by a , decade the actual changes in the structure of the Soviet economy that were introduced during 1957-60".

(Bruce J. McFarlane: op. cit.; p. 151).

The Leningrad Party Conference (1948)

On 22-25 December 1948, there was held a

“. joint conference (10th Regional and 8th City) of the Leningrad (Party -- Ed.) organisation".

('Political Archives' (1990): op. cit.; p. 153).

A few days after the conference,

" . . . the Central Committee received an anonymous letter maintaining that, although the names of P. S. Popkov, Y. A Kapustin and C. F. Badayev . . . had been crossed out in some of the ballots, A. Y. Tihkhonov, Chairman of the Counting Commission, had told the conference that they had received unanimous votes".

('Political Archives (1990)': op. cit.; p. 153).

The Central Committee investigated the ballot concerned, and it was discovered that

" . indeed, four delegates had voted against Popkov, two against Badayev, fifteen against Kapustin, and two against Lazutin".

('Political Archives (1990)': op. cit.; p. 163).

The Country-Wide

Economic Reforms (1949)

By January 1949, the revisionists felt in a strong enough position to introduce on a country-wide scale the 'economic reforms' proposed by Vosnesensky which would prepare the ground for making profit the regulator of production.

"In January 1949 an overhaul of the price system were into effect….. As a result the prices of many basic materials and freight charges increased to double or more".

(Robert Conquest: op. cit.; p. 105).

"On 1 January 1949, wholesale prices were raised very considerably".

(Peter J. D. Wiles: 'The Political Economy of Communism'; Oxford; 1962; p. 119).

described as Voznesensky's

“. . . swingeing reduction of subsidies".

(Archie Brown (Ed.): 'The Soviet Union: A Biographical Dictionary'; London; 1990; p. 43).

It must be noted that:

“.. . in 1950, after Voznesennsky's fall, this policy was reversed and the prices of producer goods were again reduced -- to be cut again in 1952". (Robert Conquest: op. cit.; p. 105).

The

All-Russia Wholesale Fair (1949)

In 1948:

“. . . Voznesensky suggested that an international fair be staged in Leningrad".

(Peter Deriabin: op. cit.; p. 313).

As a result, on 10-20 January 1949, an All-Russia Wholesale Fair was held in Leningrad.

On 13 January 1949, after the fair had opened, the Prime Minister of the Russian Federation. Mikhail Rodionov*.

" . . . sent Malenkov*, Secretary of the Central Committee, a message saying that an All-Russia Wholesale Fair had opened in Leningrad and that trading organisations from other Soviet republics were participating". (Mikhail Rodionov: Message to Georgi Malenkov, 13 January 1949, in: 'Political Archives (1990)': op. cit.; p. 153).

Malenkov circulated Rodionov's message to Lavrenti Beria*, Nikolay Voznesensky and Anastas Mikoyan*, writing on it:

"Please take a look at Comrade Rodionov's message. I consider projects of this kind must be carried out with permission from the Council of Ministers (i.e.. the government — Ed.)". ('Political Archives (1990)': op. cit.; p. 153).

The

Politburo Action against the Leningrad Conspirators (1949)

Members

of the

Politburo of the Central Committee of the CPSU were by now satisfied that leading Party members

in Leningrad

were engaged in a

conspiracy seeking

to divert the Party's

policy away from Marxist-Leninist principles and to drive a wedge between

the

Leningrad Party and the Central Committee.

On 15 February 1949, the Politburo of the CC of the Communist Party adopted a resolution 'On the Anti-Party Actions of Comrades Aleksey A. Kuznetsov*, Mikhail I. Rodionov and Pyotr S. Popkov'. The resolution strongly criticised the named Party members for 'anti-state actions'.

The accusation was made in it that:

“. . the All-Russia Wholesale Fair in Leningrad, organised by Kuznetsov, Rodionov and Popkov, had resulted in a squandering of state commodity stocks and in unjustifable expenditures of resources".

('Political Archives (1990)': op. cit.; p. 153).

The decision stated:

“'The Politburo of the A-UCP(B) Central Committee considers that the aforesaid anti-Party actions are a consequence of an unhealthy and non-Bolshevic deviation of Comrades Kuznetsov, Rodionov and Popkov, reflected in their demagogic flirting with the Leningrad organisation, their disparaging of the Central Committee, which allegedly does not assist the Leningrad organisation, and in their trying to put themselves forward as some special champions of Leningrad's interests, erect a wall between the Central Committee and the Leningrad organisation, and thereby distance the Leningrad organisation from the Party's Central Committee.

In this context, it should be noted that Comrade Popkov, as. First Secretary of the Leningrad Regional and City Committees of the Party, . . . is embarking on the road of circumventing the Party's Central Committee. . . .

It is in the same light that we should consider the proposal, of which the Central Committee has just learned from Comrade Voznesensky, that he should 'patronise' Leningrad. . . .

The Politburo of the Central Committee considers that such non-Party methods must be nipped in the bud, for they express anti-Party group tactics, breed mistrust in relations between the Leningrad Regional Committee and the Central Committee, and could result in the Leningrad organisation and the Central Committee, and could result in the Leningrad organisation breaking away from the Party. . . .

The Central Committee points out that when he tried to turn the Leningrad organisation into a bastion of his anti-Leninist faction, Zinoviev* resorted to the same anti-Party methods of playing up to the Leningrad organisation, disparaging the Central Committee, which allegedly did not care about the needs of Leningrad, detaching the Leningrad organisation from the Party".

('Political Archives (1990)': op. cit.; p. 153-54).

The Politburo:

“. . decided to dismiss Rodionov, Kuznetsov, and Popkov from their jobs, and handed down Party reprimands to them".

('Political Archives' (1990): op. cit.; p. 154).

Voznesensky was also reprimanded:

"The Politburo decision said: . . .

'Although he turned down Comrade Popkov's invitation to 'patronise' Leningrad, . . . Comrade Vosnesensky, a member of the Politburo of the Central Committee, was wrong in not telling the Central Committee . . . about the anti-Party proposal".

('Political Archives (1990)': op. cit.; p. 154).

Malenkov's

Visit to Leningrad (1949)

On 21 February 1949,

“.

. .

Malenkov was briefed by Stalin and despatched to Leningrad. . . .

Stalin . . .

told Malenkov that 'there have been too many danger signals about the Leningrad leadership

for us not to react'. Malenkov

was to 'go

there and take

a good look at what's going on' . . . Malenkov left by train

that very

night. The 'signals' coming

from Leningrad

alleged that, with the connivance of Central Committee Secretary A. A.

Kusnetsov, the local Party boss (Popkov — Ed.) was not taking notice of

the

central party authorities".

(Dmitri Volkogonov: 'Stalin: Triumph and Tragedy'; London; 1991; p. 520).

On 22 February 1949:

“..Malenkov told a joint plenary meeting of the Leningrad Regional and City Party committees about the Central Committee's decision of February 15, 1949 concerning Kuznetsov, Rodionov and Popkov. He declared that an anti-Party group existed in Leningrad, . . . Only Popkov and Kapustin admitted that their activities had been of an anti-, Party nature. After them, other speakers began begging for indulgence. . The resolution of the joint plenary meeting accused Kuznetsov Rodionov, Popkov and Kapustin of belonging to an anti-Party group". ('Political Archives (1990)': op. cit.; p. 154).

The

Dismissal of Voznesensky (1949)

On March 5th 1949:

“.

the Bureau

of the USSR Council of Ministers adopted a draft decision 'On the State

Planning Committee', which included Stalin's phrase to the effect that

'an

attempt to doctor figures to fit this or

that

prejudiced opinion is a criminal offence".

('Political Archives (1990)': op. cit.; p. 155).

By decision of the USSR Council of Ministers on the same date,

“Voznesensky was dismissed as Chairman of the USSR State Planning Committee".

('Political Archives (1990)': op. cit.; p. 155).

The

CC

Resolution on the Vosnesensky's Book (1949)

On 13 July 1949, the Central Committee of the CPSU adopted a resolution declaring that

" . . . the editors of 'Bolshevik' made a serious mistake in offering the pages of the magazine for servile glorification of N. Voznesensky's book 'The War Economy of the USSR in the Period of the Patriotic War".

(Resolution of CC, CPSU, 14 July 1949), in: 'Current Digest of the Soviet Press', Volume 4, No. 50 (24 January 1953); p. 15).

and took the decision

" . . . to remove Comrade P. N. Fedoseyev* from the post of editor-inchief of the magzine 'Bolshevik".

(Resolution of CC, CPSU, 14 July 1949), in: 'Current Digest of the Soviet Press', Volume 4, No. 50 (24 January 1953); p. 15).

The resolution also censured Dmitri Shepilov*, the Central Committee's Director of Propaganda, for the same offence:

"Comrade Shepilov, as Director of the Propaganda and Agitation Department of the Party Central Committee, has proved incapable of exercising super8vision over the magazine 'Bolshevik', . . . Comrade Shepilov . . . committed a gross error in permitting N. Voznesensky's book to be recommended".

(Resolution of CC, CPSU, 14 July 1949), in: 'Current Digest of the Soviet Press', Volume 4, No. 50 (24 January 1953); p. 15).

Although the revisionists were unable to save Voznesensky from criticism -- and later from arrest, trial and execution -- they were able to prevent any mention of these events in the media.

After March 1949,

“. . . it was not until December 1952 that any reference whatever was again made to Voznesensky".

(Robert Conquest: op. cit.; p. 100).

The Charge of Espionage (1949)

On 21st July 1949,

“. . . Abakumov* sent Stalin a note saying Kapustin* was suspected of contacts with British intelligence. . . . Kapustin was arrested".

('Political Archives (1990)': op. cit.; p. 155).

The Missing Documents (1949)

In July 1949,

“. E. E. Andreyev, who was appointed to the USSR Planning Committee as an authorised representative of the Central Committee responsible for personnel submitted a memo . . . alleging that the Planning Committee had lost some of its documents between 1944 and 1949.

('Political Archives (1990)':

op.

cit.; p. 155).

The mater was referred to the Party Control Commission, which:

“. prepared a memorandum 'On Voznesensky's Un-Party Behaviour', alleging that the Planning Committee had reduced industrial plans, that departmental tendencies; had been imposed and wrong personnel employed at the Planning Committee, and that Voznesensky . . . had maintained ties with the anti-Party group in Leningrad".

('Political Archives (1990)': op. cit.; p. 155).

On 9 September 1949, the Party Control Commission submitted to Malenkov its recommendation:

“that Voznesensky be expelled from the Central Committee and charged with the loss of Planning Committee documents. . . . On September 12 and 13 1949, the proposal was approved by a Plenary Meeting of the Central Committee".

('Political Archives (1990)': op. cit.; p. 155).

Voznesenky's 'The Political Economy of Communism' (1949)

In the autumn of 1949:

" . . . removed from all his posts, Nikolay Alekseyevich (Voznesensky -- Ed.) sat at home and continued to work on 'The Political Economy of Communism".

(G. Potrovichev: 'He Kept His Vow', in: 'Current Digest of the Soviet Press', Volume 15, No. 47 (18 December 1963); p. 12).

According to 'Pravda' of 1 December 1963:

" .Voznesensky wrote in his unpublished 'Political Economy of Communism' that 'scientific socialism does not deny the importance of the law of value, market prices and the concepts of profits and losses".

(Bruce J. McFarlane: op. cit.; p. 162).

and expressed ideas about:

. . . harnessing the 'socialist profit' motive".

(Bruce J. McFarlane: op. cit.; p. 162).

The Arrests (1949)

On 13 August 1949:

"Kuznetsov, Popkov, Rodionov, Lazutin* . • . were arrested in Malenkov's study in Moscow".

('Political Archives (1990)': op. cit.; p. 155).

On 27 October 1949:

“. Voznesensky was arrested". ('Political Archives (1990)': op. cit.; p.155).

The

Restoration of the Death Penalty (1950)

On 13 January 1950 the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet issued:

“. a decree reinstituting the death penalty — abolished in the USSR in May 1947 -- for treason, espionage and sabotage".

('Keesing's Contemporary Archives', Volume 7; p. 10,462).

The

Investigation (1949-50)

Malenkov:

“. . . personally supervised the investigation and took part in the interrogations".

('Political Archives (1990)': op. cit.; p. 155).

A movement:

“. . was launched in Leningrad to replace officials at all levels. ……More than 2,000 leading officials… were dismissed from their jobs in Leningrad and the region in 1949-52".

('Political Archives (1990)': op. cit.; p. 156).

The Indictment (1950)

On 26 September 1950:

“N. N. Nikolayev, senior assistant to the chief military procurator, wrote the formal indictment, and A. P. Vavilov endorsed it".

('Political Archives (1990)': op. cit.; p. 156).

The defendants were:

"Nikolay A. Voznosensky,

Aleksey A. Kuznetsov,

Mikhail I. Rodionov,

Pyotr S.Popkov,

Yakov F.Kapustin,

Pyotr G. Lazutin,

Iosif M. Turko, . . .

Taisia V. Zakrzhevskuya, .

Filipp E. Mikheyev".

('Political Archives' (1990): op. cit.; p. 151).

"The charges ranged from separatism (trying to usurp Moscow's power by creating a separate Party base in Leningrad) to treason (collaboration with Yugoslavia".

(Amy Knight: 'Beria: Stalin's First Lieutenant'; Princeton (USA); 1993; p. 151).

"They were all charged with having set up an anti-Party group to conduct sabotage and subversion aimed at detaching the Leningrad Party organisation and setting it against the Party's Central Committee and turning it into a bastion to fight the Party and its Central Committee".

('Political Archives (1990)': op. cit.; p. 152).

The

Trial (1950)

The trial of the defendants in the 'Leningrad Affair' took place in Leningrad on 29-30 September 1950:

"The trial . . . took place in September 1950 at Officers' House on Liteiny Boulevard in Leningrad".

(Dmitri Volkogonov: op. cit.; p. 522 (citing 'Central State Archives of the October Revolution', f. 7,523, op. 107, d. 261, 1. 12).

According to the official record of the trial, as quoted by the Supreme Court of the USSR in April 1957:

"The

accused pleaded guilty to having formed an anti-Soviet group in 1938,

carrying

out diversionary activity in the Party aimed at undermining the Central

Committee organisation in Leningrad and turning it into a base for

operations

against the Party and its Central Committee..

. . To

this end, . . . they spread slanderous allegations and uttered

traitorous

plots. . . . They also sold

off state

property. . . . As the documents show, all the accused fully confessed

to these

the rges at the preliminary investigation and in court".

(Dmitri Volkogonov: op. cit.; p. 522, citing 'Central State Archives of the October Revolution', f 7,523, op. 107, d. 261, 1. 13-15).

All the accused were found guilty.

Voznosensky, Kuznetsov, Rodionov, Popkov, Kapustin and Lazutin were sentenced to death. Turko was sentenced to 15 years' imprisonment, Zakrzhevskaya and Mikheyev to 10 years' imprisonment.

The death sentences were carried out on 1 October 1950.

Stalin's

'Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR' (1952)

In February 1952 --- by which time Voznesensky had been executed -- Stalin criticised -- but without naming the author -- Voznesensky's anti-Marxist-Leninist theses discussed above:

Firstly,

"The law of value cannot, under our system, function as the regulator of production. . . .

If this were true, it would be incomprehensible why our light industries, which are the most profitable, are not being developed to the utmost, and why preference is given to our heavy industries, which are often less profitable and sometimes wholly unprofitable. . . .

Obviously, if we were to follow the lead of these comrades, we should have to cease giving primacy to the production of means of production in favour of the production of articles of consumption. And what would be the effect of ceasing to give primacy to the production of the means of production? The effect would be to destroy the possibility of continuous expansion of our national economy, because the national economy cannot be continuously expanded without giving primacy to the production of means of production".

(Josef V. Stalin: 'Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR', in: 'Works', Volume 16; London; 1986; p. 313, 315-16).

Robert Conquest writes that in this passage Stalin

“. . . is evidently

attacking the Voznesensky price policy".

(Robert Conquest: op. cit.; p. 105).

Secondly,

"Some comrades' deny the objective character of laws of

science, and of

the laws of political economy particularly, under socialism. They deny

that the

laws of political economy reflect law-governed processes which operate

independently

of the will of man. They believe that in view of the specific role

assigned to

the Soviet state by history, the Soviet state

and its leaders can abolish existing laws of political economy and

can

'form', 'create', new laws. These

comrades are

profoundly mistaken. It is evident that they confuse laws of science,

which

reflect objective processes in nature or society, processes which take

place

independently of the will of man, with

the

laws which are issued by governments, which are made by the will of man. But they

must not be

confused.

Marxism regards laws of science . . . as the reflection of objective processes which take place independently of the will of man. Man may discover these laws, get to know them, study them, reckon with them in his activities, and utilise them in the interests of society, but he cannot change or abolish them. Still less can he form, or create new laws of science".

(Josef V. Stalin: ibid.; p. 289-90).

As the British economist Peter Wiles* points out:

"This is clearly a blow at

Voznesensky".

(Peter J. D. Wiles: op. cit.; p. 106).

The

19th Congress of the CPSU (1952)

At the 19th Congress of the CPSU in October 1952, Secretary Georgi Malenkov endorsed Stalin's criticism of Vosnesensky's revisionist economic views -- again without mentioning him by name:

"Denial of the objective character of economic laws is the ideological basis of adventurism in economic policy, of complete arbitrariness in economic leadership".

(Georgi Malenkov: 'Report to 19th Party on the Work of the Central Committee of the CPSU (B)'; Moscow; 1952; p. 140).

The

New

Criticism of Voznesensky's Economic Views (1952)

In the political situation existing after the publication of Stalin's 'Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR' and its endorsement at the 19th Congress of the CPSU. the Soviet Marxist-Leninists were able to break through the curtain of silence which the revisionists had been able to draw around Voznesensky and his partners-in-crime.

On 12 and 21 December 1952, two articles were published in 'Izvestia' by the philosopher Petr Fedoseyev extolling Stalin's 'Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR'. On 24 December 1952 a further article was published in 'Pravda' by Mikhail Suslov*, the Chief Editor of 'Pravda', in which he agreed with Fedoseyev's conclusions and for the first time since 1949 mentioned Voznesensky by name:

"This (Voznesensky's -- Ed.) view is in essence a revival of the idealistic theory of Duhring*".

(Mikhail Suslov: 'Concerning the Articles by P. Fedoseyev in 'Izvestia', Dec. 12 and 21', in: 'Current Digest of the Soviet Press', Volume 4, No. 50 (24 January 1953)' p. 14).

Suslov's article went on to express strong criticism of Fedoseyev for failing to make a self-criticism of his (Fedoseyev's — Ed.) role in endorsing Vosnesensky's views in the 1940s:

"The question inevitably arises why he (Fedoseyev -- Ed.), who once diligently disseminated this same idealistic viewpoint and subjectivism on the nature of the economic laws of socialism, deemed it necessary to maintain silence about his mistakes. . .

'Bolshevik' passed off N. Voznesensky's anti-Marxist book 'The War Economy of the USSR in the Period of the Patriotic War' as 'the latest work of science' and praised it practically to the skies as 'a valuable contribution to Soviet economic science'. . . .

Comrade Fedoseyev's

action can only be

construed as a glossing over by him

of his own

errors, which is inadmissible for a Communist".

(Mikhail Suslov: ibid.; p. 14, 15).

Suslov's article contained the previously unpublished March 1949 resolution of the Central Committee criticising Voznesensky's book and its endorsement by 'Bolshevik'.

In January 1953, a letter from Fedoseyev dated 31 December 1952 was published in 'Pravda',in which he said:

"I unconditionally regard as correct the criticism of my mistakes in Comrade M. Suslov's article".

(Petr Fedoseyev: Letter to the Editor of 'Pravda', 31 December 1952, in: 'Current Digest of the Soviet Press', Volume 4, No. 50 (24 January 1953)' p. 15).

'Rehabilitation'

(1954)

After the death of Stalin and the domination of the leadership of the CPSU by revisionists, the latter hastened to 'rehabilitate' their executed fellow-conspirators.

On April 30 1954:

" . . . the USSR Supreme Court rehabilitated the persons who had been tried and convicted under the 'case".

('Political Archives (1990)': op. cit.; p. 157).

and on 3 May 1954:

" . . . the Presidium of the CC CPSU adopted a decision to this effect. obliging Nikita S. Khrushchev, First Secretary of the Central Committee, and R. A. Rudenko, USSR Procurator-General, to notify the Leningrad Party activists of the decisions adopted. This was done".

('Political Archives (1990)': op. cit.; p. 157).

At this point, therefore, only a limited number of 'Leningrad Party activists' were aware of the allegations of 'miscarriage of justice' in the 'Leningrad Affair'.

But the 'rehabilitation' of the conspirators made it necessary to find scapegoats to blame for the alleged 'miscarriage of justice' involved in their conviction, and responsible for the 'torture' that would account for their 'false' confessions:

Thus, shortly after the murder of Lavrenti Beria in 1953 at the hands of the revisionists, the former Minister of State Security, Viktor Abakumov, was arrested, together with five of his assistants. Abakumov was put on trial --charged with having 'fabricated a false case' against those involved in the 'Leningrad Affair'. Although the trial was stated to have been 'open', the Soviet public knew nothing of it until after those accused had been executed:

"The Military Collegium of the USSR Supreme Court . at an open court session in Leningrad December 14-19 1954, tried V. S. Abakumov (former USSR Minister of State Security (MGB)), A. G. Leonov (former Director of the MGB Investigating Division for Especially Important Cases), V. I. Komarov and M. T. Likachev (former Deputy Chairmen of the Investigating Division for Especially Important Cases). . .

The accused Abakumov, who was raised by Beria to the post of USSR Minister of State Security, was a direct participant in a criminal conspiratorial group which carried out enemy assignments for Beria against the Communist Party and the Soviet government. . . .

Abakumov

fabricated cases against individual workers in the Party and Soviet

apparatus

and representatives of the Soviet intelligentsia, then arrested these

people

and -- using criminal methods of investigation prohibited by Soviet law

—

together with his accomplices . . . obtained from

those arrested false evidence and confessions of grave state crimes.

In this manner, Abakumov fabricated the so-called 'Leningrad case'. . . in which many Party and Soviet officials were arrested without grounds and falsely accused of very many grave state crimes. . . .

The persons falsely accused by Abakumov and his accomplices have now been completely rehabilitated".

(Communique, in: 'Pravda', 24 December 1954, in: 'Current Digest of the Soviet Press', Volume 6, No. 49 (19 January 1955); p. 12).

All the accused, the communique declared, were found guilty and Abakumov, Leonov, Komarov and Likhachev were sentenced to death. The communiqué concluded:

"The sentence has been carried out".

(Communiqué: ibid.; p. 12).

At this stage -- 1954 -- therefore, it was not alleged that Beria was directly involved in the 'Leningrad Affair', merely that the 'guilty' Abakumov had been

“. raised by Beria the post of USSR Minister of State Security'.

(Communiqué: ibid.; p. 12).

Khrushchev repeats this statement in his memoirs:

"Abakumov, who actually supervised the

prosecution, was Beria's man".

(Strobe Talbott (Ed.): 'Khrushchev Remembers'; London; 1971 p. 253).

However, at his 'trial' in 1953:

“. the 'Leningrad Case' did not figure in the published accusations against Beria".

(Robert Conquest: op. cit.; p. 233).

Shortly after the trial of Abakumov in 1954, however, a document circulated by the Soviet leaders to those of other East European countries placed the blame for the 'miscarriage of justice' entirely upon Beria:

"This

circular

referred to the so-called 'Leningrad Affair'. . . .In the 'secret

circular Beria was now held responsible for the whole thing".

(Wolfgang Leonhard: op. cit.; p. 72, 73).

It was not until the infamous 20th Congress of the CPSU in February 1956 that the 'rehabilitation' of the conspirators in the 'Leningrad Affair' and the trial of Abakumov were made more widely known in First Secretary Nikita Khrushchev's secret speech to the Congress. But even this speech was not published in the Soviet Union until the 1980s.

The 'blame' for the alleged 'miscarriage of justice' was now placed upon Stalin, who was said to have 'personally supervised' the case. Krushchev alleged:

“The so-called 'Leningrad Affair' . . . was fabricated. Those who innocently lost their lives included Comrades Voznesensky, Kuznetsov, Rodionov, Popkov and others.

As is known, Voznesensky and Kuznetsov were talented and eminent leaders. . . .

The 'Leningrad Affair' is also the result of wilfulness which Stalin exercised against Party cadres. . . .

The Party's Central Committee has examined this so-called 'Leningrad Affair'; persons who innocently suffered are now rehabilitated and honour has been restored to the glorious Leningrad Party organisation. . . .

Stalin personally supervised the 'Leningrad Affair'. . . .

When Stalin received certain materials from Beria and Abakumov,. . . he ordered an investigation of the 'Affair' of Voznesensky and Kuznetsov".

(Nikita Khrushchev: Secret Speech to 20th Congress, CPSU, in: Russian Institute, Columbia University (Eds.): 'The Anti-Stalin Campaign and International Communism'; New York; 1956; p. 58, 59, 60).

However, in his memoirs, Khrushchev himself disposes of his earlier story that Stalin initiated false charges against Voznesensky, recounting that in 1949, after Voznesensky's dismissal in 1949:

"I remember that more than once during this period Stalin asked Malenkov and Beria: 'Isn't it a waste not letting Voznesensky work while we're deciding what to do with him?'

'Yes', they would answer, 'let's think it over'.

Some time would pass and Stalin would bring up the subject again".

(Strobe Talbott (Ed.): op. cit.; p. 251).

At this time, the name of Georgi Malenkov was not mentioned in connection with the. 'Leningrad Affair':

"In his (Khrushchev's -- Ed.) secret speech of 1956, he did not mention Malenkov in this connection".

(Wolfgang Leonhard: op. cit.; p. 177).

But

after Malenkov

came to realise the true nature of the revisionist conspirators and was

removed

as USSR Prime Minister, secret internal Party

documents began to blame him for participating

in the 'Leningrad Affair'.

In February 1955:

“. . Malenkov had to resign as Prime Minister, and shortly afterwards an internal Party circular openly accused Malenkov of sharing the responsibility for the 'Leningrad Affair".

(Wolfgang Leonhard: op. cit.; p. 176-77).

However:

“.

. . it was

not until July 1957, after the showdown with the 'Anti-Party

Group' (Kaganovich*,

Molotov*, Malenkov, etc. --

Ed.) that Khrushchev asserted flatly 'Malenkov was one of the chief

organisers

of the so-called 'Leningrad Case'" .

(Robert Conquest: op. cit.; p. 101).

Thus, 'blame' attributed by the revisionists for the 'miscarriage of justice' in the 'Leningrad Affair' was not based on any historical facts.

It

was

shifted from one scapegoat to another according to the changing tactical needs of the revisionist

conspirators.

It is of interest, however, that in his memoirs Khrushchev describes the 'Leningrad Affair' as apparently 'a model of justice':

"The Leningrad case was a model of justice. It gave the impression of being handled in accordance with all the proper judicial procedures. Investigators conducted the investigation, a prosecutor handled the prosecution, and a court trial was held. The active members of the Leningrad organisation were invited to observe when the accused were interrogated in the courtroom. Then the accused were given a chance to say something in their defence". (Strobe Talbott (Ed.): op. cit.; p. 256).

Khrushchev goes on to refer to Voznesensky's final plea in court:

"Voznesensky's stood up and spewed hatred against Leningrad. . . . He said that Leningrad had already had its share of conspiracies; it had been subjected to all varieties of reactionary influence, from Biron* to Zinoviev".

(Strobe Talbott (Ed.): op. cit.; p. 256-57).

He expresses surprise that Kosygin escaped arrest and execution:

"As for Kosygin, his life was hanging by a thread. Men who had been arrested and condemned in Leningrad made . . . accusations against him in their testimonies. . . . Kosygin was on shaky ground from the beginning because he was related by marriage to Kuznetsov. Even though he'd been very close to Stalin, Kosygin was suddenly released from all his posts and assigned to work in some ministry. The accusations against him cast such a dark shadow over him that I simply can't explain how he was saved from being eliminated along with the others. Kosygin, as they say, must have drawn a lucky lottery ticket".

(Strobe Talbott (Ed.): op. cit.; p. 257).

In fact, Kosygin's escape from justice was due not so much to luck as to he intervention of Malenkov and Mikoyan, who testified to Stalin (wrongly) that

Kosygin was not involved in the conspiracy:

"Both Malenkov and Mikoyan assured Stalin that Kosygin was not party to the collusion".

('Annual Obituary: 1980'; New York; 1981; p. 796).

And despite his anxiety to place the 'blame' for the 'Leningrad Affair' on others, Khrushchev declares:

"I admit that I may have signed the sentencing order".

(Strobe Talbott (Ed.): op. cit.; p. 256).

Published by:

The Marxist-Leninist Research Bureau,

Cambridge R, Essex

REFERENCES VOZNESENSKY

BROWN, Archie (Ed.): 'The Soviet

Union: A Biographical Dictionary'; London; 1990.

CONQUEST, Robert: 'Power and Policy in the

USSR: The Study of Soviet Dynasties'; London; 1961.

DEDIJER, Vladimir: 'Tito Speaks:

His Self-Portrait and Struggle with Stalin'; London; 1953.

DERIABIN, Peter: 'Watchdogs of Terror:

Russian Bodyguards from the Tsars to the Commissars';

Bethesda

(USA); 1984.

DJIUS, Milovan: 'Conversations with Stalin';

Harmondsworth; 1963.

GIFFEN, Janice: 'The Allocation of

Investment in the Soviet Union: Criteria for the Efficiency of

Investment', in:

Peter Wiles (Ed.): 'The Soviet Economy on the Brink of Reform: Essays

in Honour

of Alec Nove'; London; 1988,

KNIGHT, Amy: 'Berta:

Stalin's

First Lieutenant'; Princeton (USA); 1993.

LEONHARD,

Wolfgang: 'The Kremlin since Stalin'; London; 1962.

LEVITSKY, Boris: 'The Uses of Terror: The

Soviet Secret Service: 1917-1970'; London; 1971.

MALENKOV, Georgi M.: 'Report to 19th Party

Congress on the Work of the Central Committee of the CPSU (B)';

Moscow; 1952.

McCAGG, William O., Junior: 'Stalin

Embattled: 1943-1948'; Detroit; 1978.

McFARLANE, Bruce J.: 'The Soviet

Rehabilitation of N. A. Voznesensky --Economist and Planner',

in: 'Australian

Outlook', Volume 18, No. 2 (August 1964).

MEEK, Ronald L.: 'Studies in

the Labour Theory of Value'; London; 1956.

RUSSIAN

INSTITUTE, Columbia University (Eds.): 'The Anti-Stalin

Campaign and International Communism': New York; 1952.

STALIN, Josef V.: 'Economic

Problems of Socialism, in the USSR', in: 'Works', Volume 16; London;

1986.

TALBOTT, Strobe (Ed.): 'Krushchev Remembers';

London; 1971.

UL M, Adam B.: 'Stalin: The Man and his Era';

London; 1989.

VOLKOGONOV, Dmitri: 'Stalin:

Triumph and Tragedy'; London; 1991.

VOZNESENSKY, Nikolay : 'War Economy of the

USSR in the Period of the Patriotic'; Moscow; 1948.

WILES, Peter J. D.: 'The Political

Economy of Communism'; Oxford; 1962.

: 'Annual Obituary: 1980'; New York; 1981.

--- : 'Correspondence of the Central Committee of

the

Communist Party of Yugoslavia and the Central Committee of the

All-Union

Communist Party (Bolsheviks)'; Belgrade; 1948.

'Current Digest of the Soviet Press'.

'Keesing's Contemporary Archives'. 'Political. Archives of the Soviet

Union'.

2. VOZNESENSKY

BIOGRAPHICLA NOTES (WITH * ABOVE)

ABAKUMOV,

Viktor S., Soviet Marxist-Leninist politician (1894-1964); USSR. Minister of State Security (1950-51);

judicially murdered by

revisionists (1954).

BERIA,

Lavrenty P., Georgian-born Soviet

Marxist-Leninist politician; 1st, Party Secretary,

Georgia (1931-38); USSR Commissar of Internal Affairs (1938-45);

member,

State Defence Committee (1941-55); USSR Premier (1941); marshal (1945);

USSR

Deputy Premier (1953); judicially murdered by revisionists (1953).

BIRON,

Ernst J., German-born Russian adventurer

(1690-1772); became lover of Russian Empress Anna

Ivanovna (1727); to Russia as her grand chamberlain (1730); count (1730); regent of Russia

(1740);

arrested and deported (1740).

CONQUEST,

G. R. Robert A., British diplomat, poet and historian (1917- ); research fellow, London School of Economics (1956-58);

literary

editor,

'Spectator' (1962-63);

senior fellow, Columbia University, New York (1964-65);

fellow, Woodrow Wilson International Centre, Washington (1976-77); research fellow , Hoover

Institute,

Stanford. (1977-79, 1981‑

)

DEDIJER,

Vladimir, Yugoslav

revisionist politician (1914-90); director of information

(1949-50); Professor of Modern

History, University of Belgrade

(1954-55);

expelled from LCY (1954); fellow, St. Anthony's College, Oxford (1962-63); research

associate, Harvard University,

(1963-64).

DJILAS,

Milovan, Yugoslav revisionist politician (1911- ); member, Politburo. CPY (1940-54);

vice-president

(1953-54); removed from all posts

(1954); resigned from Party (1954); imprisoned (1956-61, 1962-66).

DUHRING,

K. Eugen, German

idealist philosopher and economist (1833-1921).

FEDOSEYEV,

Petr N., Soviet revisionist philosopher (1908-

); researcher, Institute of Philosophy (1936-41);

Chief Editor,

'Bolshevik' (1941-49); Chief

Editor,

'Party Life' (1954-55); Director, Institute of Philosophy (1955-62); Academician (1960);

Vice-President,

USSR Academy of Sciences (1962-67,

1971-86)); Director, Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1967-71).

KAGANOVICH, Lazar

M., Soviet Marxist-Leninist

politician (1893-1991); Secretary,

CP,

Ukraine (1925-28); Secretary, CC., RCP (1928-30); Party Secretary, Moscow (1930-35); USSR

Commissar of

Transport (1935-37, 1939-40);

USSR

Commissar of Heavy Industry (1937-38); USSR Commissar of Fuel Industry (1939-41); Member, State

Defence

Committee (1942-43); Minister of

Building Materials Industry (1946); Party Secretary, Ukraine (1947);

USSR Deputy Premier (1947-52);

expelled from Party

(1962); manager, Sverdlovsk Cement Plant (1957-63).

KAPUSTIN,

Yakov F., Soviet revisionist politician (1904-50); 2nd Party Secretary, Leningrad (1945-49); found

guilty of

treason and executed (1950).

KARDELJ,

Edvard , Yugoslav revisionist

politician (1910-79); Deputy Premier (1945-53);

Minister of Foreign Affairs (1948-53); President, Federal

Assembly

(1963-67).

KOSYGIN,

Aleksey N., Soviet

revisionist politician (1904-80); Mayor, Leningrad (1938-39); USSR Commissar of Textile

Industry (1939-40); USSR Deputy

Premier (1940-43); USSR Minister

of Light

Industry (1948-53); Member, Politburo,

CC, CPSU (1948-52, 1960-80); USSR Minister of Industrial Consumer Goods (1953-54); USSR Deputy

Premier

(1953-64); USSR Premier (1964-80)

KUZNETSOV,

Aleksey A., Soviet revisionist

politician (1905-50); major-general (1943); 1st

Party Secretary, Leningrad (1945-49); Secretary, CC (1946-50);

found

guilty of treason and executed (1950).

LAZUTIN,

Pytor G., Soviet revisionist politician (1905-50); Party Secretary, Leningrad (1941-43); Deputy Party

Secretary, Leningrad (1943-44);

Deputy