Organ of Alliance Maxist-Leninist (North America) $4.00

A L L I A N C E ! A Revolutionary Communist Quarterly

2004: Volume 2: Issue 2:

June to September 2004

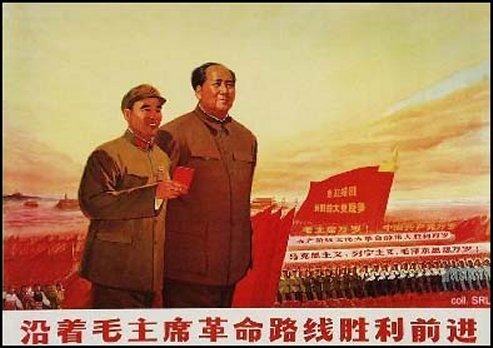

Book Review by H.D.Benoit: On Lin Biao's Demise

Yao Ming Le, 'The Conspiracy and Murder of Mao’s Heir'.

London: Collins, 2003.

In

his political diary, Albanian Marxist-Leninist Enver

Hoxha commented that the official Chinese government version of

the death

of Mao Zedong’s

onetime heir, People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Marshal Lin

Biao sounded like:

“an

episode of James Bond.”

(E. Hoxha, Reflections on China, vol. II, 1978, p. 645)

Indeed,

the story put out by the Xinhua News Agency with its tale of exploding

oil rigs, artillery attacks, runaway trains and pitched gun battles

abroad

out-of-control airplanes which then crash to Earth has all the makings

of an

Ian Fleming pot boiler. Needless to

say, the Albanian statesman, and World

opinion greeted the received version of

Lin's death with extreme skepticism.

For over thirty years the true events surrounding the fall of one of

China's

major twentieth century political figures – commander of the PLA,

leader of the Cultural Revolution, Mao's heir apparent – has remained a

mystery.

In

1983 the silence was broken by

the appearance of the book "The Conspiracy and Murder of Mao's Heir",

by

one Yao Ming-Le.

Yao (a

pseudonym)

challenged the Chinese government's version of Lin's last days.

Drawing on classified materials,

interrogation reports, confessions, and unpublished

memoires, the picture Yao

painted of the former PLA Marshal's demise not only surpassed the

cloak-and-dagger sensationalism of the official story,

but drew on other

literary metaphors beyond that of Fleming.

Yao's image of the Lin Biao Affair

treads Shakespearean ground and culminates in a

penultimate event that

is straight out of Mario Puzo. Two

decades since its orignal publication, Yao's book has been reissued by

Collins

of London.

Although its version of

events is not above criticism itself, 'The Conspiracy and Murder of

Mao's

Heir' - deserves a second look in that it offers an

interesting and quite

feasible explanation not only for Lin's fall but for why, so many years

after

the fact, the details remain a closely guarded secret.

The Facts.

Born

in 1908, Lin Biao attended the Whampoa

Military Academy, which was a nerve center of radical, nationalist, and

anti-imperialist activism in the

1920s.

Lin first joined Mao in 1928 and quickly became one of the Communist's

most distinguished field commanders in the civil war against the

(Nationalists.)Kuomintang He participated in The

Long March and made a name for himself as an authority on guerrilla

warfare. A battlefield injury in

1938

caused Lin to retire from active service.

He took up the position of President of the Political-Military Academy

at Maoist headquarters in the

mountains of Yenan. Between 1939 and 1942 he represented the

Chinese Communist Party

in the Soviet Union.

After

World War II, when fighting

broke out again between the Communist and Nationalist forces, Lin led

victorious campaigns in Manchuria and

northern China, taking Beijing in

1949.

Moving his troops southwards, Lin

secured the city of Wuhan and Guangzhou (Canton.)

Thereafter he served as head of the South-Central Party Bureau

and Military Region, a position he maintained until 1956.

An undisclosed illness kept Lin out of

active political involvement throughout the late 1950s. He played no

part in

the Korean War.

(C. Dietrich, People's

China, 1986, pp. 38-39, 80.)

By

1959 Lin had returned to the political center

stage, rising to the position of membership in the Chinese Communist

Party's

Political Bureau's

Standing Committee and holding the Defense Ministry

portfolio.

Lin became a staunch

advocate of maintaining the PLA's guerrilla traditions versus the

modernization

and professionalism urged by PLA

commander Peng

Dehuai. In 1962 Lin succeeded Peng as commander of

the PLA and immediately began a rectification program among officers

and

troops. Lin's reforms stressed political

education within the PLA and emphasized revolutionary fervor over

equipment and

weaponry,

ultimately culminating in the abolition of ranks in the PLA.

(Ibid., pp. 59, 62, 80, 148.)

Lin

became the main proponent of

the People's War Thesis which argued that the anti-imperialist struggle

was a worldwide movement in which

every national liberation movement must rely

on its own

masses – a theory which conveniently

allowed Vietnam to go unaided in its battle against

US imperialism. (Ibid., p. 171.) In 1965, Lin published the

article "Long Live the Victory of

People's War" which stated that

".

. . to make a revolution

and to fight a people's war and be victorious, it is imperative to

adhere to a

policy of self-reliance, rely on the strength

of the masses in one's own

country, and prepare to carry on the fight independently even when all

material

aid from the outside is cut off. . . "

(W. Chai, ed. Essential Works of Chinese Communism, 1972, p.

396.)

Lin

worked assiduously to develop

a cult of Mao in the PLA. Lin compiled

some of Mao's writings into the handbook, The Quotations of Chairman Mao,

and ensured that the text was mass produced and distributed; first

within the

PLA, later throughout the People's Republic.

Come

the Cultural Revolution, the

PLA, under Lin's command, effectively took over the role the Communist

Party

once played in ruling the country.

After removal of former President Liu Shaoqi at the Ninth Communist

Party

Congress in 1969, Lin rose to near total military power and

placed

second in

rank behind Mao Zedong in the Party.

The Party constitution was amended to specifically name Lin as Mao's

successor.

(Dietrich, pp. 179, 181, 185, 198-207.)

So

much is known.

The Official Story.

In

the fall of 1970 Lin sent his son, Lin Liguo,

who held rank in the air force, on a secret mission to China's largest

cities.

His task: to organize a network

of loyal and trustworthy military officers to

be known as the Joint Fleet.

This circle was to be the nucleus of a conspiracy to organize a

military

coup that

would topple Mao Zedong from power and serve as Lin's 18th

Brumaire.

The

plot, code named Project

571 (the Chinese characters for this number contain the phrase "armed

uprising"), the conspiracty was a fiasco from

the get-go. Three attempts were made on Mao's

("B-52" in the plotter's language) life:

an airplane attack on the his

residence in Shanghai;

the firing of artillery against his private train en route

from Shanghai to Beijing;

the dispatch of an assassin disguised as a courier to

his home in Beijing.

When all three failed - the last on the evening of

September 12, Lin Biao, his wife, his son, and several other

conspirators

scrambled to board the

Trident jet plane at an airport in Beijing.

The

seizure and confession of the

assassin implicated Lin in the plot.

Mao and Premier Zhou

Enlai called a late night meeting at

the Great Hall of the People to assess the situation.

While they deliberated, the Trident took off.

Although Lin had planned to fly south to

gather military support for his coup, he apparently changed his mind

once he

was airborne and decided to

seek refuge in the Soviet Union. As the Trident approached the

Mongolian

border, a gun battle broke out inside the plane causing it to

crash.

Lin Biao and his party all died in the

crash. (Ibid., p. 213-17; Hoxha, pp.

612, 641-51, 733-45.)

Yao's

Reinterpretation.

Few

accepted the official version

of the events of September 1971. Some

historians have suggested that Mao had become uncomfortable with the

power Lin

and the army had acquired and planned a purge. In this scenario, Lin

and his

high military commanders, sensing Mao's fading support,

attempted a preemptive coup

d'etat.

Yaos's

account is far

different. According to Yao, there were

two separate conspiracies. The first, Project 57 1, was organized by

Lin Liguo

and

merely called for Mao's assassination.

This was cancelled by Lin Biao in

favor of a more elaborate plan code-named Jade Tower Mountain for the

cluster of luxurious villas outside Beijing.

There Mao was to be trapped. Lin's scheme called for secret

assistance

from the Soviet Union in staging a mock attack on China.

This would give him

the excuse to declare martial law, take Mao and Zhou into "protective

custody," eventually having them killed, and seize power

for himself.

The main impetus for the plot was development of two factions within

the

Chinese leadership.

The first led by

Zhou wanted reconciliation with the United States and some kind of

alignment

with US imperialism with the end of "modernization"

of the economy

and society.

The second, led by Lin

himself, foresaw a rapprochement with Soviet Revisionism and the

continuation

of Lin's "People's War" policies.

More and more Mao supported the Zhou position – and that meant the end

of Lin's power and influence.

The

announcement that US

President Richard

Nixon would visit China the next year sent the plotters in

motion.

The apparent reconciliation with the United States and a further

deterioration of the already soured relationship with the Soviet Union

made it

imperative that Jade Tower Mountain be launched as soon as possible.

The date

chosen was the day Mao returned from a trip south, on or about

September 11.

Meanwhile, however, Zhou Enlai had apparently tricked Lin's daughter, Lin

Liheng, into revealing her brother's conspiracy if not that of

her father.

Zhou alerted Mao to the danger and the two set a trap for Lin.

Gangster Dinner.

Mountain < style="font-family: helvetica,arial,sans-serif;">villa.

Mao himself launched the celebration by uncorking a bottle of imperial wine sealed in a Ming dynasty vase 482 years earlier. At the banquet delicacies

< style="font-family: helvetica,arial,sans-serif;">flown in from all across China were served. At one point, Mao used his chopsticks to pluck tiger tendons from a platter and place them on Lin's plate.

< style="font-family: helvetica,arial,sans-serif;">After a dessert of fresh fruit, Lin's wife, Ye Qun mentioned that it was growing late; she and her husband should be leaving so that the chairman could

rest from his trip. But Mao seemed reluctant to break up the jolly gathering and urged them to stay on another half hour. Just before 11pm. Mao saw

the couple to their waiting car. Minutes later, on the road descending from Mao's villa, rockets fired by an ambush party recruited from the Chairman's

private guard destroyed the car and its passengers.

< style="font-family: helvetica,arial,sans-serif;">< style="font-family: helvetica,arial,sans-serif;">

Zhou Enlai personally verified that the charred bodies were indeed

those of Lin

Biao and Ye Qun, suggesting to Mao that a proper explanation for

the defense

minister's disappearance be concocted so that Lin would not end up

"looking like a hero." Mao told the Premier to handle the details

of

the cover-up as quickly as possible.

In

Yao's account of the conspiracy, it was

Lin Liguo who, on learning of his father's death, fled in the Trident.

When

pursuing Chinese fighters launched

a successful missile attack, the plane

crashed just over the border in Mongolia.

Conclusion.

Ultimately,

Yao Ming Le's version

of the Lin Biao Affair is as difficult to prove as the official story

is

difficult to accept.

It does however,

have the virtue of explaining the reasons for the rift between Mao and

Lin in

solid political terms (not merely based on "jealousy"

or

"ambition") and points to the logical consequence of Mao and Zhou's

embrace of the United States.

Moreover,

it provides a rationale as to why China's present rulers, the direct

heirs of

Zhou's protégé Deng

Xiaoping and the beneficiaries of

Zhou's

pro-Us imperialist policy, would wish to keep truth about Lin Biao's

last days

hidden and buried.

Although

the truth may never be

known, Yao Ming-Le's The Conspiracy and Murder of Mao's Heir is

compelling reading and offers much potential

insight and food for thought into

one of contemporary history's turning points.