“ALLIANCE!”

MARXIST-LENINIST

FALL-WINTER

2005

________________________________________________________________

”MY LIFE WITH

ENVER”;

Memoirs Volume I By Nexhmije Hoxha

Nobody but Enver Hoxha deserves

the expression:

“Glory goes to the ones not asking for

it”

__________________________________

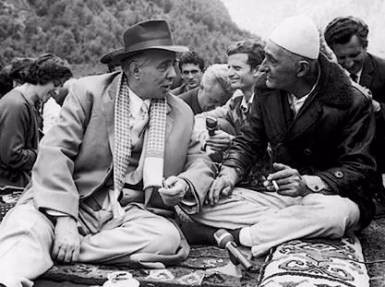

Shefqet Peci, Enver Hoxha, Adil

Carcani

___________________________________________________________________________________________

COPYRIGHT:

Of the original work

belongs to the

author;

and of this translation jointly

between the

author and the translators - Alliance Marxist-Leninist

First published in Albanian; by “LIRA” Tirana 1998 (Print Run: 2000).

All

Photographs obtained from web

Publishers Preface – Alliance

This translation was commissioned and edited, with authorisation from Nexhmije Hoxha.

It was undertaken and effected by an Editorial Board drawn from the Communist League (UK) and Alliance-ML (North America). All board members, are former

members of the now defunct ‘Albania Society’ organised by W.B.Bland.

All web-materials of this book are available to be distributed - but copyright is held by this board in association with Nexhmije Hoxha.

All permissions to copy this material on the web or in print format will be freely given, provided that the material is prefaced with the above statements.

Should there be any errors remaining in translation, we apologise for these, and stress that they are solely the responsibility of the Editorial Board noted

above – not the author.

We are publishing this initially as a series on the web. In due course we will be publishing the entire authorised translation as two volumes in a bound version.

November 2005.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

1. Authors Preface

I decided to write these memoirs about my life with Enver when I felt a

strong

need to suppress the torturing loneliness of my prison cell. I started

with

memories from our youth, our life together, the first meeting and love

- that

had connected the two of us so much. I had never even talked to my

children

about these matters, and I have kept these memories to myself,

throughout my

life.

With the passing of time, our ideal life together was embellished and

transformed into a source of endless happiness, and into a moral

strength that

kept me alive in very difficult situations and circumstances.

Sentenced to 11 years of imprisonment, under absurd charges, it had

been

already determined that I would not be released until I was over 80

years old.

It is for that reason that I decided to

write these memoirs, so that they are left to my children, for them to

learn

about the life experiences of their parents, before they were born, and

when

they were little. And, even later, when we had not been able to find

the time,

to talk to them about these things.

So, my children came to learn of them gradually, by reading notes that

I had

secretly written in prison. They were brave enough to become my muses

together

with their families – they helped me to fulfill the promise that I had

made to their

father, my Enver.

At the suggestion of many comrades and friends, I decided to publish these memoirs, hoping that I would be able to satisfy the wishes of many veterans, the co-fighters of Enver; as well as to answer the curiosity of the new generations who would not know Enver as the leader of our country and people for nearly 50 years.

During the 7 years of social and political collapse in our country,

much was

said and written about Enver and his work, including much which was

absurd,

banal and even monstrous. In these memoirs I do not want to dwell on

the many

deceits and obscenities thrown into the Albanian political arena. I

only

reminisce and describe Enver just as he was, during his life, the war,

work,

political activities, and with family and friends. Fifty years is a

rather long

period and the memories reflected in this book are not scientific

analyses of

the history of that period and the role of Enver Hoxha. Even as

memories they

cannot completely cover that time span.

But being

confined to a prison

cell, it was these memories that kept me going, and it was in such a

situation

that I began to write them down - when allowed to do so and when I had

the

chance.

Each memory brought back others until they became too many to be

included in a

single volume and I therefore decided to divide them into two books.

Book I, is the one you have in your hands, “My L

It includes first acquaintance, our love, our meetings during the time

of the

National Liberation War, our life in the family after liberation; the

daily

routine of life and work of Enver, encounters with missions sent by the

Yugoslavian Communist Party, and their agents in our Party (whose aim

was to

include Albania as a seventh republic of the Yugoslav federation); the

close

friendship with the SU (Soviet Union) during Stalin's time and, later,

the

betrayal of the stigmatized revisionist N. S Khrushchev and the ones

following

him. As chronologically ordered, these memoirs reach the year 1973,

although a

strict chronology is not necessarily adhered to within each chapter.

Book II reflects “The last ten years of my life with Enver”. The

memories in

this book are somewhat detached from each other, and this period was a

rather

disturbed time for the Party and our government too. Towards the end of

1973,

Enver suffered his first heart attack. Since the recent years of

"democracy" there has been much speculation with regard to Enver's

health. But, based upon the evidence that I have, I can categorically

deny the false

rumors regarding Enver's inability to continue working in his highly

responsible office. The years following were full of activities,

whether in the

political arena or in his personal creativity. This is evidenced by his

wide

ranging activities during this period, his many political initiatives

and the

several editions of memoirs that he wrote in addition to his

ideological or

political writings.

During 1974-1975, Enver had to fight against anti party activity, anti-socialists and anti-nationalist who were associated with some of the party members. I write about these in my memoirs and show how Enver handled them and survived these difficulties.

Much speculation has circulated regarding the relationship between

Enver and

Mehmet Shehu. Therefore, in the second book, I have dedicated a whole

chapter

to the special character this relationship had, and of the long

collaboration

and suicide of Mehmet Shehu.

A special part of this second book is dedicated, not only to personal

memories,

but also to Enver’s arguments on the

nature of the relations with the Communist Party of China and the

Certainly

I couldn’t leave out a

description of his character and personality, as a man of cultural

interests,

and of a broad mentality. Enver especially respected men and women of

scientific, artistic and literary backgrounds. It is with great

discontent that

I have had to read from many politicians, writers and intellectuals'

various

invented and denigrating charges, which are completely untrue.

With regards to his relation with the people - the straight-forward

people -

Enver was always a popular leader; with his collaborators he behaved as

a

friend and respected teacher, as he did with the revolutionaries and

Marxist

Leninists of other countries; he was a diplomat with politicians and

foreign

friends; and with his family and friends he was a HUMAN.

I apologize to the readers in the case of any minor inconsistencies,

who should

take into consideration that these memoirs were written down when I was

imprisoned without any documentation

available. There I was not even allowed to use my husband’s books, with

which I

could check and refresh my memories. I could not do this even after I

was out

of prison. The first six months of 1997 are well known for the

political

turmoil within

With all the difficulties encountered in the preparation of these

memoirs, I

would like to say that they wouldn't have come to light without the

support and

concrete contributions of friends who have assisted me as advisers for

such a

publication; and those who as editors who undertook the publication of

this

edition. I will not mention their names for the moment, for reasons

which are

clearly understandable, yet I express my gratitude, and my respect

towards

their benevolence and consistent stance in spite of unknown storms

passing over

our people and country.

I also express my gratitude to the publishing house that undertook

bringing

into the light my collected memoirs.

2. First introduction to Enver

It was because the war involving the people and its’ Party, that

Enver and

myself first met and then united. Any couple in love preserves as

beautiful

memories, their first meeting, their first introduction. Some may write

poetry,

some may sing songs; someone else waits for the beloved in the park, on

the

street, outside the schoolyard or next to the steps of the apartment.

This is

what usually happens during peacetime.

What about in wartime, in an undercover situation? Is love born? When

you are

young, love is born anytime, like flowers in the spring. The war, in

spite of

its wilderness and awe can’t suffocate or dry up this vivid human

feeling.

I became

acquainted with Enver for

the first time at the Meeting for the Foundation of the Communist Youth

that

took place on November 23rd 1941, immediately after the foundation of

the

Albanian Communist Party. (November 8th 1941)

I had

never seen or heard about

him before. I was part of the Shkodra Communist Group, whereas he was

involved

in the Korca Communist Group. Even though many attempts were made to

unite

these youth groups, I had had the chance only to meet some girls and

boys from

the Youth group, but none from Korca.

It is a

well-known fact that Enver

led and organized the demonstration of October 8th 1941, as a joint

action of

communist groups, at the eve of the Party’s foundation. Here, it was

for me the

first time to be in the front line with Enver. But we still had not

met.

I think that if the demonstration had not been successful, the Communist Party would never have been founded on November the 8th. There were some communists, such as the heads of youth groups, who did not agree to the foundation of the Party. They tried also to sabotage the demonstration. We communists, were aware that, on October 28th in the morning (as a protest against the ceremonies organized by the fascist invaders to commemorate the fascist march toward Rome as well as the Italian attack against Greece), we would have to wait at the appointed bases for the news as to whether the demonstration would take place or not.

It is a

known fact that Enver,

Qemal Stafa, Vasil Shanto and other communist companions, were to carry

out

this action, a baptism of fire for the unification of the groups and

the

foundation of the Party. After subsequent debates, sometime in the

morning, the

comrades in favor for action were victorious, and they set off to

organize the

demonstration. I was waiting at a friend’s house in

In such clashes there is no time to stay and observe. Right beside me I

noticed

a policeman who had captured young Zeqo Agolli, whose family I knew

very well.

Influenced also by what Enver was doing, I jumped and clambered among

them, in

order to separate them. The policeman seemed surprised, as a highlander

he

probably didn’t feel like pushing and throwing me down to the ground,

so he

freed Zeqi. All around one could see the gun butts of Italian and

Albanian

police raging over the heads of the demonstrators. Nevertheless the

demonstrators kept struggling with fists and umbrellas, which they had

taken

with them since it was rather cloudy weather, or even, possibly to

protect themselves.

In a moment the order was passed: “Everyone towards the

After the chants in front of the Government building “we want our

friends”,

“Glory to Albania” “Long Live Liberty” “Down with Fascism” etc, the

prime

minister, Shefqet Verlaci, appeared on the stairs and mumbled

something. Who

would listen to him? Scared by the wild chanting, he went inside and,

after

some moments, our two friends were set free, bleeding. I remained

speechless

when I noticed that one of them was my brother Fehmi (a high school

student,

friend of Pirro Kondi and others, two years younger than me, i.e. 18

years

old). Companions held him on their shoulders. They wanted him to say

something,

but he wasn’t able to. One of his eyes was swollen, closed and

bleeding. I was

worried that his eye had been damaged, but blood was coming from a

wound over

his eyebrow and probably he had been hit there and on the chin too.

Beating his

tongue made it difficult for him to speak. I went to him and separated

him from

the crowd. After we had left the crowd of demonstrators, we got into a

cart and

went home. I am not going to stop here to describe the shock that my

mother

went through, and her cries when we were cleaning the wounds. She kept

saying:

“Poor me, I only have two sons (sic!) and both of you are involved in

the

struggle …!”

Less than two weeks passed and we were sent the news that “ the

Albanian

Communist Party had been founded”. The Party that we had dreamed of and

wished

for was at last a reality for us true communists!

Two weeks after the foundation of the Communist Party of Albania, a

meeting was

convened to lay the foundations of the Communist Youth Movement. From

all youth

groups 12 delegates were selected to take part, I was the only female.

The

meeting took place in the house of Sabrije (Bije) Vokshi, the aunt of

Asim

Vokshi, the hero who gave his life in the Anti-fascist struggle in

The house of Bije was very suitable for such meetings due to its

location in

occupied Tirana, where the fascist terror was becoming more and more of

a

burden. The house was located at the end of the large Boulevard, close

to the

where the train station sits today. It was set among small houses,

individual

shops, and typical Tirana houses, built of mud bricks. Her house was

also

suitable for our meetings because it had two entrances. One was deep in

the

alley, and the other had an exit on another road that connected the end

of the

boulevard with the street named after to the martyr Siri Kodra. The

latter, is

now part of the peripheral ring-road that takes you to the hospitals.

Participants of these meetings were assigned a time to show up, and a “code” (a particular knock on the door) so that the landlady wouldn’t open the door to anyone else, even to her friends and relatives who might visit at the time the meting was about to take place. At the end of the meeting in case of danger, one could leave by jumping from the low courtyard wall, to yard to yard of the nearby houses. Qemal had escaped like this many times. Bije’s house was an important base for him. Bije’s neighbors were very kind and patriotic, anti-fascist people, who behaved as if they didn’t notice the comings and goings of the youngsters in the old lady’s house.

On November 22nd in the afternoon, the invited comrades started to come

in one

after another. I remember that it was dusk when I arrived at Bije's

house. I

went in, and everybody sounded joyful. They stopped for a moment,

probably they

saw a girl comrade, and they might have been telling raffish jokes. We

greeted

each other with the slogan "down with fascism and liberty to the

people”.

We shook hands warmly, even though at the time we didn’t know much of

each

other, since we belonged to different youth groups.

The room in which we had gathered, had comfortable straw mattresses. A

black-sheeted iron coal range rumbled merrily with a powerful fire that

had

reddened it in places. The room had become dim with smoke. It wasn’t

cigarette

smoke, the comrades mostly didn’t smoke, as they were very young. The

smoke

came from the bread slices, which were on the range being toasted. On a

square

table, next to the window, lay the caps of the comrades, on which they

had

placed the bombs, which seemed like red apples in fruit bowels. Of

course the

window was covered with a thick blanket, so that the light couldn’t be

seen

from outside.

The owner of the house could only offer tea from “tiliacaea”, which

yielded a

very nice aroma. She had to fill up the teapot many times. There were

no china

glasses, only aluminum ones, like those used in the military, which

were not

very suitable to drink from since they got hot and could burn your

lips. The

comrades couldn’t wait for it cool down. Furthermore there were not

enough

glasses for all of us, so we had to take turns. The impatient ones

would take

sips. Anything would make them laugh and joke. It was there that I

first got to

learn of Italian humor. One could distinguish Ndoc Mazi, who got jokes

started,

and Qemal would keep on the same line. Ndoc could laugh and die in the

same

way; he died like a hero, together with the other heroes from Vig.

All of us laughed at their humor. This is how Enver found us when he entered the room. He had entered from outside into the kitchen where he had left his overcoat, cap, and everything else he possessed. At first, when he entered the room, what was most noticeable was his well-built body, the tallest of all comrades in the room. His dark complexion, his very vivid eyes, his black, rather wavy hair. He was wearing a “doppiopetto” jacket of light colors, beige with brown stripes. Underneath he was wearing a handmade woollen beige pullover with a high neckband, out of which appeared the shirt collar. His trousers were sporty and fashionable for the time, somewhat wide, covering long brown boots up to the knees.

I hadn’t noticed Qemal leaving the room. When Enver entered he was with Qemal . He introduced Enver saying: “This is comrade Taras , a member of the provisionary Central Committee of the Communist Party, founded two weeks ago, on November 8th. He has been delegated to participate in this meeting in order to help set up the Communist Youth Movement.”

Most of the people present, were aware of the fact that he was actually

Professor Enver Hoxha. I myself had only seen him from a distance and

had heard

another name, a non-Albanian one, Taras.

What was this other name about? I presumed that was a nickname and, as

I heard

later on, he was given that name from his friends because of his body,

to an

extent like a well known character from Russian literature, Taras

Bulba, a

famous popular fighter.

Enver came around shaking hands with everyone, whilst Qemal did the

introductions. Enver would stop at everyone, smiling and chatting with

all of

them, wondering where he had met one and then the other. When he

stopped at me,

Qemal said, this is comrade Nexhmije Xhuglini, about whom I have been

talking

to you. Then he mentioned some other things about me, which made me

blush. I

interrupted and said; please Qemal let’s stop this and drop the

subject…..

When Enver neared the range, he stretched his hands forward to get

warmer and

noticed the bread toasting, saying “Ahhh this is delicious”…one of his

friends

asked him whether he wanted to have some tea and he replied “Why not,

with

great pleasure”. He had his tea and than added ”What if we start the

meeting?”

It was around 9 o’clock. After the middle of the room had been cleared

two or

three desks were placed there. The meeting started. Representing the

Central

Committee of the Party was Enver Hoxha; on his right there was Qemal

Stafa, on

his left Nako Spiru, then myself, and on both sides sat all the

delegate

comrades.

Enver

chaired the meeting; he

introduced Qemal Stafa as the one who had been assigned by the Central

Committee of the Communist Party to work with the Youth Groups. Then he

read

the greeting speech of the Provisionary Central Committee of the

Albanian

Communist party (written by himself, and whose original is now in the

Central

archives of the Party).

Enver presented a report about the importance of the foundation of the

Communist Party and the decisions made there to unite the people on a

national

liberation front, to fight against fascist invaders, the traitors of

As we saw then as later, at every meeting and in every speech about and

for the

youth, even at the beginning, Enver Hoxha spoke with passion. It was

still

November of 1941. This is why it is understandable that his words about

liberty

and the future awaiting us, lit up a fire in our young hearts. It gave

wings to

our thoughts and aspirations for the future. Our dreams seemed more

attainable

now, more concrete.

When Enver Hoxha got to the end of his speech, the room was filled with

silence. Certainly, there was no applause, not only because of secrecy,

but

also because applause was not yet part of our meeting style since we

hadn’t won

any victory yet. What we wished for was just a beautiful vision, which

one day,

certainly would be transformed into reality through our struggles, our

blood,

our life and youth.

In the midst of this silence, Enver proposed to have a break. Not

because we

were tired, but it seemed we all needed to be released from emotional

tensions.

We all moved around. Enver moved to the other room to smoke a

cigarette. We

also followed him. We surrounded him; despite the fact that we were

supposed to

be on a break and, because we felt much freer, we started to ask

questions and

chat.

When we went back to the meeting room, which, during the break had been

freshened up, Qemal Stafa took the floor. In the beginning he spoke

about the

importance of the foundation of the Party. Then he underlined the

situation and

the struggle of the communist youth.

After Qemal, it was decided that the meeting should be ended since it was past midnight. We moved to an adjoining room used for resting and sleeping. There were no mattresses, no beds, except for one that was Bije’s, the owner of the house. They gave that bed to me. On both sides of the room there were rugs and straw filled pillows. Comrades laid down their heads on the pillows and their bodies on the rugs. Their feet were on wood. They were covered with their overcoats, close to each other, since it was a cold night and the room had no fireplace. Some of the friends preferred to stay in the meeting room, which was heated by the range, sleeping on stools and supporting their heads on their crossed arms on the table.

Even though we were in the capital city, we slept as partisans, fully

clothed,

with our guns lying ready close to us, in case of danger. In the room

where we

slept, there was a cupboard in the wall, at the bottom of which there

was a

place for documents to be kept. A wooden stool covered it and on it

were Bije’s

clothes. In the ceiling was a space to keep guns. As Enver has said,

the house

of Bije Vokshi was an arsenal of guns and bombs. We compared Bije to

Pellagia,

mother to Pavel Vllasov. In the atmosphere of these meetings our

imagination

would fire up as in the work of Gorky “The Mother”. But I might say

that this

mother of ours, an Albanian one, didn’t fear guns, she was used to

outlaws,

their guns and wounds. In this room there was also a special area in

which

Qemal would develop his pictures. There is well known picture that he

took of

Enver. In it, he is wearing a moustache for a fake identity card. But

from what

I know, it wasn’t used for long, since the enemy obtained various

documents, so

the picture was burned, since it could have identified Enver.

I will digress from the meeting, to tell you about an interesting

episode about

this picture. On another occasion when Enver had sheltered in the house

of

Shyqyri Kellezi, he was notified that the house was being watched.

Enver left

with another comrade immediately, first asking the mother of their

friend to

deny anything she might be asked. The mother of Shyqyrri was a simple

old lady

from Tirana, nice in her manners and her humor. When the fascists

presented her

with the picture of Enver with a moustache, the poor old lady couldn’t

help

saying ‘My God’ but she immediately came to her senses, shut her mouth

with her

hand and became very embarrassed. They questioned her for a long time

asking

her whether she knew Enver, but she kept her mouth shut. She was taken

to the

police station but even there she wouldn’t answer their questions. She

managed

to convince the police that she was insane and so they released her.

The next morning of November 23rd, after we had some bread and tea, the meeting continued with discussions on both reports. The floor was given to Nako Spiru. He spoke about fascism, its risk as an ideological and military force, what it represented for intellectual scholarly youth, then he moved onto tasks for the communist anti-fascist youth.

Tasi Mitrushi took the floor on behalf of the Korca working youth,

whereas Ndoc

Mazi represented the Shkodra working youth. Pleurat Xhuvani took the

floor on

behalf of Elbasan, whereas for the Tirana student youth, Sofokli Buda

who took

the floor. I presented the news

regarding the Girls Institute of Tirana. I underlined the

positive aspect

of this institute, which provided the whole country with the teachers

it

trained there.

Enver had met with factionist Trotskyites such as Anastas Sulo and

Sadik

Premte, during the meeting for the foundation of the Party. In our

meeting

also, as a member of the youth group, Isuf Keci, tried to contradict

the party

direction on various issues, such as the Anglo-Soviet-American

alliance, on the

external framework, for the country and the role of peasantry, on the

internal

framework, and other issues.

All participants were discussing vigorously, in support of the direction of our new Party. Enver in his memoirs, commented positively about my speech, and my active participation in the debates on the incorrect perspectives of the delegate of the Youth group. During the lunch break, Enver approached and congratulated me on this. At the time I took this as an encouragement for a comrade who was participating for the first time in a meeting of this sort. At this point, I would like to stress that I vigorously participated in those ideological-political debates, only because we had already had such debates about these issues at the first meeting of the women’s comrade cells, immediately after the foundation of the Communist Party. Probably our women’s comrade cell was the first cell, as it was convened on a weekday, between November 15th and the 22nd - after the end of the party’s foundation meeting, when the foundation meeting of Communist Youth started.

Finally, after all the issues had been presented, and were addressed, we passed onto the election of Communist Youth Central Committee. It was decided that it would be composed of five people. Candidacies were presented in a way, which today, might seem strange. Numbers, not names were presented and each of the numbers listed the characteristics of a person. I believe the candidacies were proposed in principle by the Provisionary Central Committee of the Party, and supervised by Enver Hoxha and Qemal Stafa; based also on the discussions taking place in that meeting. The characteristics listed included: duration of involvement in communist groups, what was the activity in which the person had been involved, education, origin, social background, profession etc. all in all, these were general characteristics on which the delegates would base their vote.

The candidacies presented were approved by everyone. The names of the comrades elected are well known. Elected as political secretary was Qemal Stafa; Nako Spiro was elected organizational secretary; and Nexhmije Xhuglini, Tasi Mitrushi and Ymer Pula were elected as members. The latter was from Kosova and when he was sent to organize the Communist Youth, he was replaced by the distinguished, brave and active worker, Misto Mame. Later changes occurred, since Qemal Stafa was killed less than six months after the meeting. Nako Spiro replaced him as secretary general, and Misto Mame was appointed as organizational secretary.

Since my

election to the Central

Committee of Communist Youth I was assigned to work with the Tirana

Youth, and

I was elected as its political secretary. I was also assigned to work

with the

organization of the Communist Youth in

What I call a kitchen was a large area, characteristic of Tirana houses, sometimes called house of fire. It was extended with compressed soil and lacked a ceiling and a fireplace. A thick chain hung from the blackened trunks caused by smoke, and was used to hang copper jugs or mess tins. When meetings such as ours were organized with many participants, big kettles were placed on the grills where pasta would be boiled or even polenta. But we Dibra People call the polenta ‘Bakerdan’. That very day, when the meeting was over, some of the most active delegates, led by Qemal, asked Bije to prepare halva: “The fascism halva, Bije, at the meeting, we decided to bury it! This is a closed question!”

And everyone would laugh their hearts out as if this “job” was a wedding. !......

These are very beautiful unforgettable memories. And they are memories that are a mixture of joyful moments and sad feelings, such as those for the friends that you have fought and laughed with, and have since “left”.

3. The day in a new course of my

life.

On April 7th 1942, as usual on the Commemoration Day of the Albanian

invasion

by Fascist Italy, a demonstration took place in Tirana. It was one of

the best

organized and most powerful ever, by the student youth, workers,

communists and

anti-fascists.

Normally demonstrations occurred in the morning, before noon. All the

youth,

having been notified of this activity, would arrive gradually, as if by

chance.

They would fill the upper part of the boulevard that today leads you to

the

train station, looking as though they were having their everyday walk.

At the

moment when the organizer gave the signal, the girls would unfurl the

flag, and

the walkers, so notified, would start marching towards

This time it was different. Thinking that the demonstration would be

organized

as usual, in the morning, the Fascist invaders and their mercenaries

were alert

from the early morning hours. Behind the Municipality (now the

The

demonstration, as planned,

broke out in the afternoon and, instead of it being directed towards

The girls were right in the front. They were, as usual set in the first line, since it was thought that it would be rather difficult for the invaders to hit a woman. And this is what happened. When the Fascists and mercenaries pointed their bayonets towards our chests, we told these poor Albanians that had accepted to serve the occupiers: “Shoot at us, shame on you, behaving in such away with your Albanian sisters and brothers!” At least the Albanian police stepped aside since they didn’t know exactly what to do.

After

this break, the

demonstrators continued their march. The crowd stopped in front of the

Madrassa. Amidst the chanting of various slogans, a short speech was

held and

then the demonstrators were disbanded.

I had participated in all the demonstrations, but apparently, in this last one, I had been more noticeable. So, I was now an implicated figure. On the morning of April 12th, someone knocked on my door. The son of my uncle, Skender Xhuglini, went outside to answer it. He found armed militia at the front door.

A feeling of alarm passed through the room. It was obvious that they had come to arrest me. There was only one way to escape, and that was through the courtyard door! The greatest concern I had was not for myself but for the others. It might seem paradoxical, but one night before, Drita Kosturi, through her sister, had entered a college of nuns that gave embroidery lessons etc., and had brought a young Italian nun to be sheltered temporarily in our house. She was anti-fascist and for this reason she didn’t want to lead a nun life. We had to find a solution to this problem. The Italians must be prevented from capturing her. In the meantime, as Skender was chatting with the militia at the door, we took care of the nun. We dressed her in some clothes of my mother’s and since her head was shaved she had to wear a scarf to cover it. We also told her to behave like a mute, so that she wouldn’t have to speak.

After Skender had seen off the militia and closed the door from inside,

we

finally breathed a sigh of relief. When we asked him how he had got rid

of the

militia; he replied that he had put the militia under some pressure by

saying:

“how can you an Albanian highlander, a faithful person, come here to

take an

Albanian girl and then hand her over to the Italians? Don’t you feel

ashamed?

Apart from that, she is not in here…” , in addition to other words. The

militia

had answered: “ OK, I will come again another time…” but, as we learned

later,

he had come to make us aware, indirectly, that I had been included in a

list of

people to be arrested. He was the brother of a communist and had become

part of

the militia, on the orders of the Party itself, in order to provide

‘inside’

information.

Of

course, there was no time to

loose. As soon as he left I got dressed and I told my mother I would

let her

know of where I would be and where we could meet. I would also let her

know

where the nun could be taken. We hugged each other and then I left the

house.

From that moment my parents were left all alone with Skender, because

my

brother Fehmi Xhuglini, even though he was 2 years younger than me, was

forced

to live undercover. He left Tirana to go to Elbasan, since he was

directed to

work with the youth there. Our house was situated in a blind alley,

that

connects Pazari I Ri (

Because I was a wanted person it was not possible for me to leave the house and walk up to the end of the street because I might have run into a patrol. I therefore headed towards Qemal Stafa Road moving from courtyard to courtyard and from door to door of the various neighbor’s houses. After reaching the end of the street, I relaxed and started to think about where I might get some lunch before going on to attend the meeting of the First Consultation of Party’s Activities to which I had been invited. I decided to go and pay a visit to some relatives of my father. It was seldom that I and my mother went to visit this family, so questions such as “What might have happened to her? What might have brought her here” were unavoidable. Anyway, it was not necessary to give explanations. I stayed there until 4 p.m., then I set off for the house of Bije Vokshi where the meeting would be held.

By dusk, all the delegates of the districts had arrived. This was an activity meeting to which all

political and organizational secretaries, elected in the conferences of the districts were invited, to make reports and receive consultations.

These conferences were begun after the foundation of the Party and the establishment of the basic organizations of the Party. Also invited were members of the Central provisionary Committee (7 people), and the Central Committee of Communist Youth (of which I was member).

The tables were arranged differently from the meeting for the

Foundation of the

Communist Youth, since the number of participants was much bigger. The

tables

surrounded the four angles of the room, creating a space in the middle.

Though

not all were true tables, on two angles were trunks supported by boxes.

The

stools to sit were constructed more or less in the same way, since it

was

impossible to find enough chairs for all the participants. The

chair-person of

the meeting sat in between two doors, next to the wall that separated

this room

from the porch. I happened to sit on a corner of the table attached to

the

chair-person’s table. In some of the plenary meetings

Enver

would come and sit on the

corner of the same table and would converse with me.

Once he told me: You have a nice pen, it seems to write beautifully.

Would you

give it to me? ’’ “You can take it if you really want it” – I replied

smiling,

“but as you can see it is a lady’s pen”.

It was as thin as a finger and had a red silk threaded plume. I was fond of that black and red pen which I had had for a long time, ever since the time when I used to see it in the window of the bookshop of Lumo Skendo (Mithat Frasheri).

This shop

was situated on

O natura

, O natura,

Perchè non rendi poi

Quel che prometti

Ai figli tuoi

[nature, oh nature, why can’t you offer your sons what you promise.

Italian in the original]

When I told Enver that the pen had been purchased with my first salary

as a

teacher and that I had done some teaching only for three or four months

in

1942, until the day I was forced to leave home and school; he asked me:

“Is it

only this pen you could buy with your first wages?” – “No”, I replied,

“I

bought also a coat for myself, because I didn’t have one. I also began

giving a

lump sum to my maternal grandmother (a quarter of a napoleon which was

about 1

dollar and equal to 25 lek at that time), so she would have some pocket

money.

The remaining part of my wages, I gave to my mother, for the household

expenditures.”

When I mentioned the money for my grandmother, Enver started laughing

and asked

me:

“What about your grandmother? What would she need the money for?”

I

replied: “She needed the money

to buy cigarettes, since she was not the kind to ask for money from

everyone. “

“If I had known” – said Enver – “That your grandmother smoked, I would

have

sent her a packet of cigarettes from ‘Flora’ Do you know where Flora

is?”

”I know” – I told him – “We pass by that road very often”.

”Why haven’t you visited then?” – he asked me, whilst his smiling eyes

were

shining more and more as he glanced at me.

”Why should I come” – I replied in a devilish way – “I don’t smoke and

I don’t

drink either”.

”Well, I know, but if you had come, we could have met each other

earlier” – he

continued on this track.

These words and jokes of Enver, later took on a meaning, which I hadn’t

sensed

at the time.

Usually, during wartime, these types of meetings were quite intensive and covered a wide range of topics of national importance and, for security reasons we worked both day and night. The consultation started at around 8 p.m. (April 12th 1942) and continued on until 3 or 4 o’clock a.m.

There

were so many delegates that

there was some difficulty in making the sleeping arrangements. Some of

the

comrades would lay down wherever they thought possible, or sit on

stools. Some

laying their heads on another’s shoulders or even on the meeting

tables. I,

being the only female, was as usual, more “privileged” in such cases. I

would

use Bije’s bed; the only bed in the house, and I would sleep with my

clothes on

and take my shoes off. As soon as I lay down I fell asleep.

I don’t know what the time might have been when I heard a slight noise. The dawn was breaking. At first I thought I was dreaming; I heard some steps that passed by my bed and someone stopped, pulled up the blanket and covered my shoulders and back, even though, as previously mentioned, I was sleeping with my clothes on. The first thought that crossed my mind was that it was my dear mother. But when this someone removed a lock of hair from my face, I woke up completely, but didn’t open my eyes until I heard the steps move away.

When I opened my eyes I saw Enver’s back as he entered the kitchen. I

am not

sure whether he had slept or not, because when I went to bed I had left

him

smoking on the porch of the house.

What did I feel in those moments? What did I think? I can truly say

that at the

time I didn’t think that this act of his was an expression of love. I

was

pleased that among the leaders of the party we had such comrades. I was

getting

to know Enver during the meetings and could see that they would take

care and

behave warmly with us, just as Enver had acted at that moment with me.

I was

especially delighted that a friend approached me and took care of me,

even with

the simple act of pulling the blanket over me while I slept, because,

it was on

that same day that I was nearly arrested and I had left my home and

parents. He

was a friend who, with his jokes and his warm hand touching my

forehead, wanted

to create a homey environment for me, trying to relieve me of the

sadness of

being separated from my beloved parents, whom my brother and I had left

alone

at home.

This is all I thought at that moment since I didn’t know Enver very

well: I

didn’t know his age, or whether he was married or not. I was 21 at the

time,

but he looked much older due to his well-built body, and I wouldn’t

have

thought of anything else during those days.

It was

wartime. War is war and not

a wedding ceremony. It doesn’t leave you time to have fun and love. It

was

nearly midday, when into the house of Bije Vokshi came one of our

guards, who,

together with two other friends, had been keeping watch around the

house for

suspicious movements. They let us know that there was a patrol

wandering about.

The comrades of the Central Committee decided to take some preliminary

measures

in order to be prepared. They ordered the guards to keep their eyes

open and

follow the movements of that patrol on the road. In the meantime lunch

was

prepared.

After lunch we thought that we would continue with the meeting, while always keeping a lookout for any suspicious movements. But we received some bad news. Njazi Demi had been arrested! He owned a house that was a base for our undercover comrades. The house was called “the house of the frogs”. It was next to the oldest bridge in Tirana, and was classified as a cultural monument, and was close to the building where the Italian headquarters was situated during the war (after the war this building was occupied by the Central Committee of the Communist Youth). Later the same building was given to the Committee of the Anti-fascist National liberation War Veterans.

This friend, now arrested, presented us a great risk, even for the

meeting to

take place. This was because Njazi Demi had close contacts with Bije,

and under

torture, could be forced to expose us. It was immediately decided

therefore

that the meeting be postponed to the next day and all the delegates

left. They

were notified that the meeting would continue, not in the same place,

but in

the house of Misto Mame.

Before we left, Enver gave some directives; the two tables were to be

placed in

the two different rooms, whereas the other two where to be moved to the

kitchen. The long stools without backrests (there were many of them),

were

taken to the porch, and placed around the walls. Some of them were

taken to the

kitchen as well. So the room where the meeting was taking place was

empty now,

though not at all clean since the comrades had moved around with their

dirty

shoes. There were cigarette-butts on the floor as well. I had to roll

up my

sleeves and start washing everything. Bije would go outside at the well

and

fill in the buckets with water and bring it to me. Meanwhile Enver had

defined

the interval of time for the comrades to leave from both the doors, so

that

they wouldn’t be noticed by the neighbors or by any spies that might

happen to

be around.

When all

the friends had left,

Enver having been the last in the house, came and leaned on the door

case. He

was looking at me as I was scrubbing the wooden floor with a brush. I

was on my

knees on the wet floor.

”So you can wash perfectly well, can you not?” – he said laughing

”Did you think that I couldn’t? I am

from a Dibra background”.

- “Those who have a Gjirokastra background are quite the same” – he

said.

- “I don’t know, I haven’t seen Gjirokastra Houses, but I do know

something

else. In communism women and men will be equal; so- I continued

smiling- men

will have to work just like the women do, that is to say that you have

to take

those carpets that Bije brought and dust them outside…..! “

- “Right, comrade, with great pleasure”, he said and without taking

long, went

outside, dusted them and brought them inside.

Together

with the owner of the

house we put the carpets in place, we set the rugs on two corners of

the walls,

put down the pillows for the guests, covered the table next to the

window, put

an ashtray on it and a flower pot. The house now seemed ready for even

a visit

by any “severe guests” with pistols and chevrons. Enver warned Bije to

check to

see if any of the comrades had possibly left any bombs or pistols under

the

rugs or pillows; then he asked me:

”Where are you going tonight?” He knew I had left home and couldn’t go

back

there.

“ I don’t know”, I replied “I don’t know where to go! “

“What do you mean by that? Don’t you

have an aunt or an uncle here in Tirana?”

”No, I have no one in Tirana other than some relatives of my father. I

have

never been to their house for dinner or lunch. If I visit them it means

I will

have to let them know what the situation is, and I don’t really know if

they

can shelter me after that.”

Let us bear in mind that it was the end of April 1942, a few months after the Communist Party was founded, and a few days after the powerful demonstrations. Those were the days of fascist terror, days when people were arrested and killed.

Then Enver said:

”You will join me wherever I go then.”

I

couldn’t do otherwise. I didn’t

even have the time to think. I put on my clothes very quickly. In that

period

of struggle we tried to disguise ourselves in every way possible. We

mostly

used elegant dressings, wore hats in order to cover parts of our face,

or wore

silk scarves on our heads, which was very fashionable at the time. Our

real

saviors were the dark sunglasses. You might ask where we could find

these

expensive elegant clothes that helped avoided the suspicions of the

fascists

and their spies. Friends, supporters, the people helped us. On some

occasions I

have also used a black yashmak, which I didn’t like much because the

fanatic

Dibran Muslims wanted very young girls to wear it. I hated the idea and

couldn’t walk with it on. We had to move fast, the girls wearing the

yashmak

daily had to walk slowly and were always accompanied on the road.

Lowering the

yashmak was not only forbidden, it was also unwise.

When

Enver saw me with a brown

scarf and the dark sunglasses, he couldn’t help making compliments on

the

transformation I had gone through. We started laughing. Then we said

goodbye to

the owner of the house and left. Enver arranged his hat on his

forehead, took

the bicycle and when we reached the outside door, told me:

“You will sit here in the front. Watch your legs, they shouldn’t touch the chain…. “

I was surprised. I had never been on the bicycle with a boy. Then all

the way I

would feel so uncomfortable. I began to resist: ‘No I can’t “; and in the same time I felt funny.

Then I

told him;

”It’s a shame, people will see us, they will say how does it happen

that such a

signorina gets on a bicycle?! “

”There’s no time for discussions,” he said, “it is getting dark and the

house

we are going to is on the other side of the city.”

As a

matter of fact it was getting

late, and the time of the “coprifuoco” [curfew, Italian in the

original] was

near. All the people had to go into their houses at a certain time,

depending

on the season, as soon as it started to get dark. It was worse to walk

with

Enver. It was very risky had the militia stopped us on the road. He was

well

equipped with bombs and a revolver. Enver was also sentenced to death

and was

one of the most wanted by the fascists and their hunting dogs.

I didn’t resist for long and got on the front side of the bicycle. At

that time

I didn’t weight more than 50 kg.

My first

adventurous trip on a

bicycle was not associated with any incident. Some years after the

liberation

of the country, when we met foreign friends, Soviets, Bulgarians etc.

and

exchanged ideas about our traditions. They would also ask us about the

way we

had known each other and become married. Enver would always say joking:

“I

kidnapped Nexhmije, according to the Albanian tradition, but I didn’t

use a

horse. I used a bicycle”… “

We would laugh endlessly. This memory is marvelous for me even today

when I

think of it.

The house

where Enver took me that

night was a one-story house, near the Electric Power Plant, in front of

“Qemal

Stafa” school, in

Both sisters were very hospitable and kind to me. They also prepared for us something quick to eat. After dinner we really enjoyed the discussion. We started to discuss the origin of man. I was very passionate about the Darwinian theory on species evolution and the struggle for survival of the species. So I became very active, just like in the time in the groups, when we had read

publications of Engel’s’ on this issue. Enver was only listening and most probably was trying to let me have my say. I was only able to understand this later. When we were alone he told me: “members like you from the Shkodra group give much importance to theoretical studies”.

And

indeed, we were some of the

best students in the class. But the workers too were eager to learn

more. Vasil

Shanto for example was one of the most distinguished workers, and so

was Qemal,

his best friend; he would take good care of Vasil’s education. So did

Kristo

Themelko, he wouldn’t leave without first having us explain to him the

“Anti-Duhring” of Engel’s. We in turn would make him teach us how to

use the

revolver.

After we

talked with Enver, I went

to sleep with the sisters in their room. It was impressive, how they

would take

care of their hair and their bodies. In the bedroom there were only two

beds,

on the floor. In one of the beds the two sisters would sleep while I

would

sleep in the other. The other room was much better furnished, with two

sofas

covered in red fur and a big carpet. At a corner there was a covered

mattress

that obviously was used anytime that Enver would show up.

The following day we woke up early. We had a coffee there and

separately set

off to Misto Mame’s home, which was far away, in the other part of the

town,

near the place where he was killed. From that square, surrounded by

rack

berries, you could get to

As soon

as I got there, the other

participants of the meeting started to arrive. They entered one by one.

Before

the meeting had even started, the alarm went off; the activities of the

comrades entering the house had been noticed by the neighbors and by

the

children playing nearby. They had become curious. Justifiably so: why

were

there all those well-dressed men, some in hats, some in caps, some in

dark

sunglasses…?!

This

house was had to be written

off for the meetings too. Some comrades were sent to see what the

situation was

at the Frog’s house and also with the person who had been arrested. I

don’t

remember if he was set free or if we had make sure that he wasn’t

tortured.

Thus, due

to this difficult

situation it was decided to return to Bije Vokshi’s house and there we

continued with the meeting, with which I go into details. It has been

described

in the published documents of the Party.

After the

consultation meeting, I

didn’t see Enver until the 5th of May, the day when Qemal Stafa was

shot dead.

Chapter 4. When

Qemal Stafa was killed

I was at Gjike Kuqali's house when I heard this bad news. We were

holding a

meeting there with some youngsters. The shock was so strong and the

news so unexpected

that it was impossible to continue the meeting. Some burst into tears,

while

others were completely speechless. Someone was sent to learn more of

what had

happened.

With a deep anguish in my heart, I felt jittery and thought of Enver.

What was

he doing at that moment? Qemal was both Enver's and my best friend. I

had known

him ever since the time of the early communist groups, he was my first

teacher.

Whereas for Enver, he was his closest collaborator since the first

steps of the

foundation of the Albanian Communist Party and through the

revolutionary and

patriotic struggle to liberate the country from the fascist invaders.

Where could I find Enver at this time? I decided to go to the house

where he

had taken me by bike that strange night, and it was there that I found

him.

After my "coded" knocks, he himself opened the door. Our sad faces

showed that we both were aware of what had happened and both knew of

the tragic

ending of our comrade, Qemal. Enver closed the door, turned to me, put

his arm on

my shoulder and sat next to me on the couch in the hall, which I

described in

the notes concerning the first time I had visited this house.

I don't know how much time passed without us saying a word. We were shocked. I was about to start crying and could hardly stifle my whining, which had blocked my throat. I didn't want to seem weak either. He lit a cigarette again; he would inhale deeply (the ashtray on the table seemed a mountain of cigarette ends).

Finally

he broke the silence.

"Qemal left us, we lost him. We lost a very dear friend, a

revolutionary

intellectual with a great perspective for the Party and

After a while I asked: “What do we know? How did it happen?”

Enver started telling me that comrade Gogo (Nushi) was the only one from the Tirana Party committee who knew about the secret base where Enver would shelter us. He had also brought Shule (Kristo Themelko) who had been together with Qemal but had survived the attack and broken the siege. He had explained also that there had been three female comrades. Drita Kosturi, Qemal’s fianceé ; Maria, the fiancéé of Ludovik Nikaj and Gjystina, a cousin of Maria, married to Zef Ndoja. I was thinking that it was normal for Drita to be there, because she was seeing off her boyfriend, Qemal. He was going to leave either that day or the next for Vlora. But what about the other two girls? What were they doing there? They only know Qemal slightly and didn't have any work relations with him, or with Drita. Later it was discovered that Ludovik, the fiancéé of Maria, was a spy for ISS, Italian secret service. Ludovik, had obviously followed the movements of the two, somewhat featherbrained ladies, and had consequently discovered Qemal's Base. For me this is the most convincing explanation. The other possibility was that; one of our comrades, who had rented the base, had been arrested. Possibly the house rental document was found in his pocket. It might have been due to this, so that the base had become suspicious and later came under siege.

From what Shule had said, Ludovik had been the first to escape from the

back of

the house, in order to cover the escape of the female comrades. Whereas

Qemal

had stayed until he made sure that they had left. Qemal headed towards

the

river, but obviously, the siege had become more narrowed down and the

fascist

troops concentrated on him. Qemal had tried to withdraw, fighting until

he fell

under the hail of bullets of the Italian fascist militia and the local

mercenaries.

I think that the attitude of Drita Kosturi was poor and indecent,

having been

influenced by elements of some secret plan to mask the figure of Qemal

Stafa.

She has presented many options during media interviews regarding his

death.

Such was the case recently when she absurdly suggested that Qemal had

committed

suicide; this fifty years after his death! Qemal not only showed that

he was

brave, but also that his disposition was one of spiritual nobility. He

sacrificed

his young life in order to protect his comrades-in-arms, whoever they

were.

Enver told me he had severely criticized Shule for thinking only of

himself and

his friends, and for leaving Qemal alone without any protection. His

face was

full of gloom and made more so by his moustache; nevertheless many

hours had

passed since his meeting with Kristo Themelko. It started to get dark,

but we

didn't even think of eating. I got up and made some coffee for both of

us. We

sat on the table, in the middle of the room, where we stayed and talked

about

Qemal until very late; about how we both came to know him. I spoke

about my

first meeting with Qemal somewhere in the summer of 1937.

Passion

about literature and an

aspiration for a better-emancipated future for all Albanian society had

'hooked

me up' with Selfixhe Ciu, whose nickname was

As I

said, my first meeting with

Qemal occurred in the summer of 1937 in a Tirana house, in

I can say that it was with this meeting that I started my commitment to

the

Shkodra Youth Communist group. For some time I was unaware both that

the group

I was a member of, was named the Shkodra Group,

and the basis for its’ name. I thought that the center of our

activists

was Tirana and the leaders of our group were Vasil Shanto and Qemal

Stafa. With

the trial of many communists in 1939, we came to know about the

existence of

several other groups.

I told Enver, that I thought that Qemal didn't get a very good

impression about

my revolutionary spirit, because, not only did I not say much, but I

was also

very embarrassed. On that day, there was an incident which, when I look

back on

it, makes me laugh, but at the time caused me much embarrassment.

During our

meeting, a beautiful cat entered the room and was obviously missing the

tenants

of the house who had left it by itself. It came around my legs and then

jumped

onto my lap. I have always loved cats and without diverting my

attention from what

Qemal was saying, I started to caress the cat. Unexpectedly I heard him

say

meekly: “Leave the cat!”

And he

then went on with his conversation, about directives related to our

work. He

let it go, but I couldn't help thinking about this incident for days.

After this meeting, Qemal organized and then became leader of the

girls' cells.

This cell had members such as: Liri Gega, Fiqret Sanxhaktari, Drita

Kosturi as

well as myself. We had some meetings with Qemal, where we learned about

communist theories and the tasks we had to undertake. We also made

reports on

the work done. But these meetings with Qemal didn't last long since he

had to

leave for

Was Qemal one of those youngsters that would get engaged without first

falling

in love? I can say no. Above all, Qemal was honest and it might be that

in

certain circumstances he could have felt pressured to get engaged. I

knew Drita

Kosturi very well, and in spite of her being older than me by two or

three

classes, we got on well with each other, since we were part of the same

cell.

I freely visited her house and got to know her family members. She had

been

raised without her mother in a patriotic liberal family. She was a kind

of

anarchic revolutionary. She was open minded, but not that balanced, and

somewhat messy in her life and in her work, and didn't normally dress

well.

Although she didn't know what conspiracy was, she didn't lack courage.

I told Enver about the activities of our group during the May Day celebrations when Drita would wear a red ribbon in her hair and would go to the pastry shop on Royal Street where all the communist students would meet, including Qemal and his friends. “You probably know that shop don't you?”, I asked Enver. “It is opposite the store of the big businessman, Shaho. So the network of secret agents were very well aware that Drita was a communist, and certainly knew of the relationship that she had with Qemal.”

During our discussion, I remembered what Bije Vokshi had once told me

about

Drita. She didn't really like Drita being so disorganized and flighty.

Bije,

loving Qemal very much, had asked him once: " Son, how come you are

mixed

up with that girl?" He had answered: "Eh, dear Bije, this is the way

it is; I can't help it anymore, and she already knows all about the

bases and

all our comrades".

Qemal was

an emancipated person,

educated and free of prejudices, but one never knows. Perhaps he wasn’t

completely free from the prevailing, albeit incorrect mentality of the

communist militants who, for the sake of the group’s interests, for our

undercover communist work, and, to create bases, believed that

marriages had to

be arranged. It was due to this mentality that Zylfije Tomini married

Xhemal

Cani and, as a consequence, the house where the party was founded, was

established. They also arranged the marriage between Zef Ndoja and

Gjystina, in

order to establish the house on

When I told Enver that a communist comrade had been found for me to marry but that I didn't want to go through with it because I had never met him; he laughed and said: “Well done Nexhmije!” For him this reaction had another meaning, but I understood it only to be an approval of my reasonable attitude. I told him that this is why the foundation of the party is something more for us young women communists, because we had been saved from certain marriage alliances dyed in red and from certain allegedly golden plated chains. In fact we had had enough of the chains of our conservative families, who lived in accordance with contemporary traditions.

Following this conversation, about the mentalities and mistakes of the

communist groups of the time, Enver spoke at length to me about the

load of

work the party and the communist youth had to face. Not only had they

to work

on organizing the war against the fascist invaders and the unleashed

propaganda

of their collaborators and local traitors, but also on the enlightening

of the

minds and awareness of the common people, so that the girls and women

would be

viewed under a different light. They were to be treated like human

beings and

when the party and the people won the war, they would be entitled to

equal rights

with men.

Qemal was

a very funny youngster,

and we reminisced about his jokes. Enver told me about his efforts to

teach

Qemal how to sing Vlora songs, and how he had to join in. Qemal was

never able

to do this because he would start laughing! "Let's sing something from

Shkodra"- he would say,- and would take the banjo and play, singing

merrily. Though deep in thought when we would sit down to work, there

were

moments when we took breaks and he would suggest playing with colorful

glass

marbles which he always keep in pocket.

He was

still young and these

marbles apparently reminded him of the games of early childhood.

I also told Enver how well I remembered the power that Qemal's laughter

had, as

well as Vasil's (Vasil Shanto). When I used to visit Vasil's home I

would often

be quite shocked after my meetings with representatives of various

groups

because of the use of bad language. Once, when I was to have a meeting

with a

girl from the youth group, I couldn't believe my ears at the vulgar

language that

I heard her use; language that I wouldn't expect even a man to use!

Voicing my

displeasure, I said to Qemal and Vasil: "I will never ever attend

meetings

with people such as this." Qemal and Vasil burst out laughing because

they

were aware of what I had heard, but that I was unable to repeat it to

them.

Did you

know, I asked Enver, that

the nickname "Delicate" had been given to me by Qemal? And do you

know why? It was not because of my outward appearance but because of my

intolerance regarding bad language. And, even when Qemal said that he

thought

that there should be more refined manners and stricter attitudes (I was

not

sure if he was serious about this or not), he would laugh and make fun.

Despite

this and his youth, Qemal was the perfect educator for the youngsters

and was a

wonderful communicator and agitator with people of every age.

I also

remember that anytime he

was given the occasion, he would have warm chats with my mother. Once,

before I

had gone underground, a meeting of the Central Youth Committee took

place in my

home at which,

I also

spoke to Enver about my

last meeting with Qemal, two days before he was shot and killed. He

came to the

home of Hysen Dashi to participate in a meeting of the Youth Circuit

Committee

for Tirana. We used to call the house "February 66'" and Enver would

go there quite often. The meeting was interrupted several times because

the night

was full of tension due to the constant barking of the neighborhood

dogs and it

was known that there were patrols everywhere. In order to help relax

the young

people at the meting, Qemal expressed a wish (that unfortunately, he

would

never be able to realize) - full of joy and optimism he said - 'Our day

will

come; a day of liberty, when all of us will be able to walk along the

boulevards singing and chanting and we won't mind what others will say

of

us...".

While Enver and I were talking at the table on that day of calamity,

the owners

of the house returned from having lunch in the city. We were unaware

that it

was so late and hadn't thought about eating. The owners offered to

prepare

something warm for us to have, but we told them we were not hungry and

that some

bread and cheese would suffice. Enver also asked for some tea because

his

throat was dry from his continuous smoking. He asked them about what

was

happening in the city. They said that people were worried and were

wondering

who had been killed (those who didn't know Qemal). They also wondered

who else

had been there with him, and if anyone else been arrested or killed?

There was

a general alert and the police and fascist militia were in a very

agitated

state. Many patrols were to be seen on the streets.

We

started to talk again about

Qemal; of his courage and culture. Enver told the owners of the house

that, the

next day Qemal was to have left for Vlora to take care of some work.

They had

met on the previous day and said their goodbyes. "How could I have

known,-

said Enver with tears in his eyes- that it was a farewell and not a

goodbye?!" It had been only 7 months since the Party had been founded

and

we needed to do much work. We faced a big battle and the Party and the

People

needed as many individuals of Qemal's capabilities and stature.

After

dinner we switched on the

radio to listen to the daily news. It was difficult to listen to Radio

Tirana

during the war, because it was difficult to put up with the propaganda

of our

enemies. We listened to the

In order to honor the memory of Qemal Stafa; this patriotic communist,

one of

the main leaders of the Albanian Communist Youth, Enver purposed that

the fifth

of May (the day on which he was barbarously killed), should be

commemorated as

Martyrs' day of the Antifascist National Liberation War, against the

Nazi

fascist invaders. This day became a symbol of honor and a national

holiday.

-------------------------------------------------------END

THIS SELECTION-----------------------------------------------