“ALLIANCE!”

MARXIST-LENINIST

SPRING 2006

________________________________________________________________

”MY LIFE WITH ENVER”;

Memoirs

Volume I By Nexhmije Hoxha

Chapters 12-17

Nobody but Enver Hoxha deserves the expression:

“Glory goes to the ones not asking for it”

Anti-fascist Rally Korca, 28th

November

1939

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

COPYRIGHT:

of the original work belongs to the author;

and of

this translation jointly between the author and the translators -

Alliance

Marxist-Leninist

First published in Albanian; by “LIRA” Tirana 1998 (Print Run: 2000).

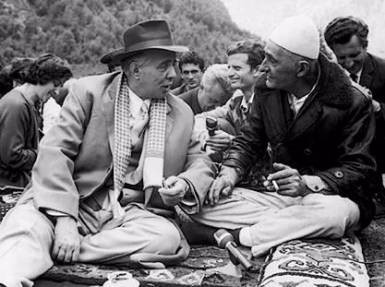

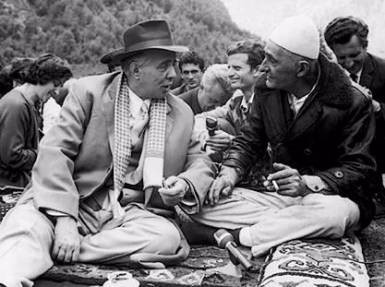

All

Photographs from: 'Enver Hoxha 1908-1985':; Tirana; 1986;

containing photos of the Archives PPSH and of Albania Telegraphic

Agency

Publishers Preface – Alliance

This is Part Four of a translation, that was commissioned and edited, with authorisation from Nexhmije Hoxha.

[PART One chapters 1-4 at

http://www.allianceML.com/PAPER/2005NOVEMBER/Chapter1_4HoxhaFIN.html

PART Two: Chapters 5-8 at:

http://www.allianceml.com/PAPER/2006/Spring_March/Chap5_8_FINAL.html]

PART Three: Chapters 9-11 at:

It was undertaken and effected by an Editorial Board drawn from the Communist League (UK) and Alliance-ML (North America).

All board members, are former members of the now defunct ‘Albania Society’ organised by W.B.Bland.

All web-materials of this book are available to be distributed - but copyright is held by this board in association with Nexhmije Hoxha.

All permissions to copy this material on the web or in print format will be freely given, provided that the material is prefaced with the above

statements.

Should there be any errors remaining in translation, we apologise for these, and stress that they are solely the responsibility of the

Editorial Board noted above – not the author.

We are publishing this initially as a series on the web. In due course we will be publishing the entire authorised translation as two volumes

in a bound version.

November 2005.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

1.

Authors Preface

I decided to write these memoirs about my life with Enver when I felt a

strong

need to suppress the torturing loneliness of my prison cell. I started

with

memories from our youth, our life together, the first meeting and love

- that

had connected the two of us so much. I had never even talked to my

children

about these matters, and I have kept these memories to myself,

throughout my

life.

With the passing of time, our ideal life together was embellished and

transformed

into a source of endless happiness, and into a moral strength that kept

me

alive in very difficult situations and circumstances.

Sentenced to 11 years of imprisonment, under absurd charges, it had

been

already determined that I would not be released until I was over 80

years old.

It is for that reason that I decided to write these memoirs, so

that they

are left to my children, for them to learn about the life experiences

of their

parents, before they were born, and when they were little. And, even

later,

when we had not been able to find the time, to talk to them about these

things.

So, my children came to learn of them gradually, by reading notes that

I had

secretly written in prison. They were brave enough to become my muses

together

with their families – they helped me to fulfill the promise that I had

made to

their father, my Enver.

At the suggestion of many comrades and friends, I decided to publish these memoirs, hoping that I would be able to satisfy the wishes of many veterans, the co-fighters of Enver; as well as to answer the curiosity of the new generations who would not know Enver as the leader of our country and people for nearly 50 years.

During the 7 years of social and political collapse in our country,

much was

said and written about Enver and his work, including much which was

absurd,

banal and even monstrous. In these memoirs I do not want to dwell on

the many

deceits and obscenities thrown into the Albanian political arena. I

only

reminisce and describe Enver just as he was, during his life, the war,

work,

political activities, and with family and friends. Fifty years is a

rather long

period and the memories reflected in this book are not scientific

analyses of

the history of that period and the role of Enver Hoxha. Even as

memories they

cannot completely cover that time span.

But being

confined to a prison

cell, it was these memories that kept me going, and it was in such a

situation

that I began to write them down - when allowed to do so and when I had

the

chance.

Each memory brought back others until they became too many to be

included in a

single volume and I therefore decided to divide them into two books.

Book I, is the one you have in your hands, “My L

It includes first acquaintance, our love, our meetings during the time

of the

National Liberation War, our life in the family after liberation; the

daily

routine of life and work of Enver, encounters with missions sent by the

Yugoslavian Communist Party, and their agents in our Party (whose aim

was to include

Albania as a seventh republic of the Yugoslav federation); the close

friendship

with the SU (Soviet Union) during Stalin's time and, later, the

betrayal of the

stigmatized revisionist N. S Khrushchev and the ones following him. As

chronologically ordered, these memoirs reach the year 1973, although a

strict

chronology is not necessarily adhered to within each chapter.

Book II reflects “The last ten years of my life with Enver”. The

memories in

this book are somewhat detached from each other, and this period was a

rather

disturbed time for the Party and our government too. Towards the end of

1973,

Enver suffered his first heart attack. Since the recent years of

"democracy" there has been much speculation with regard to Enver's

health. But, based upon the evidence that I have, I can categorically

deny the

false rumors regarding Enver's inability to continue working in his

highly

responsible office. The years following were full of activities,

whether in the

political arena or in his personal creativity. This is evidenced by his

wide

ranging activities during this period, his many political initiatives

and the

several editions of memoirs that he wrote in addition to his

ideological or

political writings.

During 1974-1975, Enver had to fight against anti party activity, anti-socialists and anti-nationalist who were associated with some of the party members. I write about these in my memoirs and show how Enver handled them and survived these difficulties.

Much speculation has circulated regarding the relationship between

Enver and

Mehmet Shehu. Therefore, in the second book, I have dedicated a whole

chapter

to the special character this relationship had, and of the long

collaboration

and suicide of Mehmet Shehu.

A special part of this second book is dedicated, not only to personal

memories,

but also to Enver’s arguments on the nature of the relations with

the

Communist Party of China and the

Certainly

I couldn’t leave out a

description of his character and personality, as a man of cultural

interests,

and of a broad mentality. Enver especially respected men and women of

scientific, artistic and literary backgrounds. It is with great

discontent that

I have had to read from many politicians, writers and intellectuals'

various

invented and denigrating charges, which are completely untrue.

With regards to his relation with the people - the straight-forward

people -

Enver was always a popular leader; with his collaborators he behaved as

a

friend and respected teacher, as he did with the revolutionaries and

Marxist

Leninists of other countries; he was a diplomat with politicians and

foreign

friends; and with his family and friends he was a HUMAN.

I apologize to the readers in the case of any minor inconsistencies,

who should

take into consideration that these memoirs were written down when I was

imprisoned without any documentation available. There I was not

even

allowed to use my husband’s books, with which I could check and refresh

my

memories. I could not do this even after I was out of prison. The first

six

months of 1997 are well known for the political turmoil within

With all the difficulties encountered in the preparation of these

memoirs, I

would like to say that they wouldn't have come to light without the

support and

concrete contributions of friends who have assisted me as advisers for

such a

publication; and those who as editors who undertook the publication of

this

edition. I will not mention their names for the moment, for reasons

which are

clearly understandable, yet I express my gratitude, and my respect

towards

their benevolence and consistent stance in spite of unknown storms

passing over

our people and country.

I also express my gratitude to the publishing house that undertook

bringing

into the light my collected memoirs.

12.

Towards a free life – in the mountains

After being on

duty with the partisans in the mountains, I left Tirana on March 20th;

the city

I would not return to until its liberation. Along with my joy, I also

felt an emptiness

in my soul. I was leaving the city in which I had grown up and gone to

school,

I was really close to the people of Tirana. I had fought with them for

their

freedom, their happiness and for a safe future for its youth. I had

also helped

in their struggle for the emancipation of the Albania Woman and for the

independence of our long-suffering homeland. Would I ever come back to

see a

liberated Tirana, free from invaders and spies, without the terror, the

curfew,

the arrests and the imprisonments?

I was quite sure

that this day would eventually come, not only to Tirana, but also to

all

Albania, because we were fighting a war with the backing of the entire

population. However, at this particular moment, was the day of

liberation in

the near or distant future?

With a false

identity card in my pocket and my mind loaded down with all these

questions, I

took the bus. I left behind the Tirana where, the Party, the guerilla

units,

and my life as an underground activist had been founded and headed for

Korca.

With me was a comrade (whom I never met) who was taking a letter from Gogo Nushi and Nako

Spiro to

Enver. He had been appointed as the courier who made the connections

between

the Korca district and the Center in Tirana. His name was Arsen Leskoviku.

Our journey took

us passed Elbasan and, up to this moment, we had had no problems.

However, just

before entering Librazhd, we were stopped by an armed patrol. There

were three

of them; one was a German and the other two Albanians who were wearing

the

uniform of the Albanian militia. They asked for our identity cards. The

German

took mine and began moving it in his hands. He raised his eyes, and

looking

straight at me said,

"Yugoslav?" I nearly had a heart attack! The name on my

identity card was Vera - a name that the Slavs use as well. I thought

that they

would ask me to get off the bus and take me for interrogation to the

post

office nearby and who knows then what would have happened. I hastened

to

explain. Although he was not Italian, for some reason I spoke to him in

Italian, thinking that I could better communicate with him. I remember

telling

him,

"No, no,

albanese, Vera, stagione, estate o primavera"

(No, no,

Albanian, Vera is a season; summer or spring).

So I waffled on a

bit. Finally he returned the identity card to me. I breathed a sigh of

relief,

and, after a while, I turned my head and glanced at the comrade who was

with

me. He had recovered himself and was quite calm; he just closed his

eyes as if

to say: "Good...". I smiled slightly as if to say: "We're

safe...".

We arrived in

Korça in the evening and stayed that night in the home of a

school friend. The

next day, at dusk, we set off for Panarit, where Enver and some

comrades from

the Central Committee and General Headquarters were. A team of 4-5

partisans

was waiting for us outside of the town. They knew the area very well

and were

to accompany us on the journey from village to village. After we had

greeted

each other, the partisans told us that armed frontists had been seen in

the

area and this was why we had to talk softly and walk carefully.

We walked in a

single file for a very long time without stopping in order to get away

from the

town. The worst thing was that the night was so dark that we were not

able to

see and it was difficult to follow the path. One comrade fell. He

apparently walked

too close to the edge of a hole in the ground, slipped, uttered a sharp

'oh!'

and then there was silence. We were shocked. We went to the place where

he had

fallen but we couldn't see anything. We called out in low voices;

"Arsen, hey,

Arsen!",

but there was no

reply. We became even more worried. Down in the hole nothing was

visible. We

tried to locate his body with the butt of a rifle, but it was in vain.

Then the

partisans found some long sticks and, in the darkness they measured the

depth

of the hole with them. After coming up with the idea of holding one

another

hand-by-hand, one of us managed to get down into the hole. When we were

told

that Arsen's body had been located we were very relieved and we hoped

that he

was alive.

They managed to

pull him up with great difficulty. I remember when they laid him down,

they

gave him a drop of raki that one of the partisans kept with him in his

water

bottle and used as medicine for various wounds. Arsen groaned. They

checked out

to see if he had broken a leg or an arm but he screamed only when they

touched

him on one of his hips. They held his mouth closed so as not to be

heard. As he

told us afterwards, he had been hurt badly in one hip when he had

fallen

because he had had a tin of meat in his knapsack and it was this

knapsack that

he fell on and severely bruised his hip. What could we do? The comrades

carried

him on their backs in turn to the nearest village where we would spend

the

night. As soon as we entered the specified base, the women of the house

put a

bed near the fire and laid Arsen down on it to help him rest up. With

the light

of an oil lamp the comrades checked him for any other injuries and

massaged his

hip with raki and olive oil until he felt somewhat better. When we

realized

that he didn't have any other serious injuries, we started joking with

him.

We told Arsen

that we would sequester his tin of meat because it was "cold steel"

that kills and might take prevent someone from fighting.

"Look, this

has interrupted your journey with us; you must stay here and will have

to eat

chicken soup of course, that is, if the frontists have left any

chickens in the

village."

Laughing, he fell

asleep.

We slept for

three hours and, after taking the letter from Arsen, we set off before

dawn in

order to avoid any confrontation with the frontists. After so many

years I

don't remember which villages we passed through or the length of the

journey.

In Panarit –

to Enver

We finally

arrived in Panarit, where Enver was living. This village was located on

a

mountainside. It was said that this was a big village, but I didn’t

share this

idea, because I couldn’t see many houses.

The house where

the headquarters was located was quite big; it had two or three floors,

together with a barn, and was completely built of stone. They led us

into a big

room, in the middle of which was a large fire, where entire trunks were

turned

into fairly hot embers, and which gave the room pleasant warmth. It was

able to

bring one back to life and make you feel relaxed after the long and

tiring

journey. In such a place, the warmth created a feeling of satisfaction,

something that I had not felt before in these years of war. This room in Albania is called a ‘room of fire’,

and around the big fireplace with no chimney, the women cooked and

stayed. These

rooms didn’t have any ceilings, but only roof timbers which were

blackened by

the smoke). Around the fire sat several comrades who worked in the

headquarters

along with partisan guards and companions. I recognized among them,

comrade Behar Shtylla.

He stood up immediately and went to inform Enver about our arrival.

You can imagine

how impatient I was to meet Enver. But Behar came back and told me that

Enver

was in a meeting.

Meanwhile the

comrades found us a place near the fire and, one after another, brought

some

homemade bread, which was very soft, some fresh sheep cheese, honey and

nuts. I

especially enjoyed the fresh cheese and the toast. Then the friends

began

talking and joking. They even had an argument as to whose life was more

difficult; that of the partisans in the mountains or that of the

underground

activists in the towns. I myself thought that the life of the

underground

activists, under the continuous worry of fascist encirclement, repeated

controls, the dangers of arrest or the maltreatment of the families who

sheltered them, was more difficult. But the partisans were correct

because they

lived in the mountains, marched and fought in very bad places, in the

winter’s

cold and frost, usually poorly dressed, in bare feet and with empty

stomachs.

One of them said:

“This fire and this food are like a dream for us…”

Of course he was

right, and the local peasants didn’t spare what they had in their

houses, in

order to honor and respect the partisans of the mountains.

While we were

talking, Enver came in. He was smiling as always. He was really

surprised when

he saw me. As he told me later; he had thought that Naxhije had come.

She was a

leading comrade of the Party in Korca. So after the first surprise, we

hugged

each other with nostalgia, forgetting to keep the “secret” of our

relationship.

Seeing us that way, the comrades laughed... Just to give a formal

meaning to my

coming, in front of the others, Enver asked:

“Did you bring

the letters we wanted? Come.”

He took my hand

and we went out. We went to the house where he was living and sleeping

with the

other comrades. The house was up in the hills so we had to do a bit of

climbing. It was a small bungalow, but to go inside you had to go up

some

stairs built over a rock, which was covered with wide stone slabs. The

house

was painted with lime, and the doors and windows were made of pinewood,

which,

in that fresh mountain air and under the heat from the sun, gave off a

pleasant

scent that allowed you to breathe freely. There were too many things

there that

made me feel very comfortable and happy.

We went into

Enver’s room. It was white because the walls were painted with lime.

The sheets

on the bed were snow-white, so were the embroidered curtains. On the

settee was

a fringed haircloth; while on the floor was a small carpet. Enver asked

immediately about the letters. He looked at them quickly.

“I will read them

carefully later”, he said

and then wanted

to hear my report about the situation at the Center. I told him many

things,

and then we talked a bit about ourselves and satisfied our yearning.

The women

of the house brought us corn bread, sheep's yoghurt and eggs. In that

fresh and

healthy climate, one had had an increased appetite and I very much

enjoyed the

food. I said to Enver jokingly:

“I saw in the house

at headquarters that you don’t live too badly…”

Enver replied,

"The peasants are friendly and hospitable and, although they are poor,

they are very kind and we owe them a lot".

The next day I

went down to some of the buildings. I don’t remember if they had been a

school

or a cantonment. A course was being held with party personnel from the

field

and the army, at which, political and ideological lectures were being

given in

order to increase the educational level of our comrades.

During the three

or four days that I stayed in Panarit I met many comrades I had known

in

Tirana. Here in the mountains among the partisans, comrades and

peasants I felt

different. Here you could move calmly and freely, something that could

not be

done in Tirana, because it was filled with terror.

During our talks

in Panarit for three-four days, Enver told me that they had started

preparations to set up a meeting larger than the Second National Liberation Conference of

Labinot. (He meant the Congress that was going to be held in

Permet).

“In this

meeting we will make very important

decisions for Albania." But we will have to work hard in order to do

this.

So I think it is not necessary that you return to Tirana now. I think

that you

should go to Permet and from there to Zagorie. There you will find the

Headquarters of the Gjirokastra-Vlora Area, and you will work there,

dealing

mainly with the youth and the organization of anti-fascist women, in

the field

and near the units acting in that area.”

I was happy about

this because in this way I would continue living a free life in the

mountains,

villages and areas where the breeze of liberty had started to blow.

I set off for

Permet and Zagorie and, for two months I worked very hard and joyfully

in these

two areas from which I have unforgettable memories. Memories from the

historic Congress of

Permet (24 May 1944) where I took part as a delegate, and

from my

activities during the German Operation of June in the Zagorie

mountains. But I

will not refer to them in these notes because I do not have many

memories about

my personal and direct meetings and conversations with Enver, who,

during this

period, was very busy. He had much of the responsibility for the

preparations,

development and compilation of the resolutions for the Congress of

Permet,

which was to be of great historical importance for the victory of the

National

Liberation Anti-fascist Movement, and for the future of our people.

13.

Unforgettable days in Lireza – among the youth

After the Nazi

operations of June, Enver, together with the leadership of the National

Liberation Anti-fascist Council, the main members of the General

Headquarters

and some members of the Central Committee of the Party, left Odrican

and went

back to Helmes (a small village in Skrapar district, with 10-12 houses

situated

on a mountain side below Marta Pass).

After the

Congress of Permet, in early July, while I was working in Zagorie, I

got news

from Nako Spiro telling me to set

off

immediately for Helmes in the Skrapar district. In time of war orders

were not

given to discussion. So although I was used to the wonderful people of

the

Zagorie region, with whom I had worked and lived for a long time, I set

off to

Helmes. We walked from village to village and after two days reached

the

destination.

Helmes village

seemed to me like a beautiful relaxing oasis. It was full of greenness,

with

trees that gave it a special grace. The apple trees were full of fruit

and the

branches were nearly breaking. Also, the grapes, even though they were

not

properly ripened, made your mouth water when you saw them. We sat for a

moment

near the drinking fountain. The water was very cold and it flowed

freely along

the side of the cobblestone street. We refreshed ourselves and relaxed

there

from the long journey. After a while some comrades came and took me to

the

offices where Enver and his comrades worked. It was a two-floor stone

built

house.

In one of the

offices, on the first floor, was Enver with Nako. We hugged longingly.

They

asked me about the affairs and the situation in the regions in which I

had

been. Then they told me why they had called me there: The First Congress of the Union of the Albanian

Anti-fascist Youth had to be prepared. Enver told me of the

importance of this Congress, which, as he put it, would give new ardor

and

strength to the union of anti-fascist youth for the final war to

liberate the

whole country. It would also create new perspectives for the youth in

the

construction of a new, democratic national Albania, and its future.

Nako talked

about the procedures we had to follow for sending out notifications,

for

choosing delegates, for the preparation of the Congress’ documents, and

reports

that would be held, etc. Then the next day he asked me to go to the

Lireza

field (the place where the Congress would be held) in order to see the

field

and to decide what measures had to be taken in the construction of some

work

cabins and also to see where to put the tents for the delegates to

sleep in. He

also wanted me to see what we could do about the equipment and

decoration of

the Congress setting.

Lireza was a

large plateau surrounded by mountains. I thought that it was a suitable

place,

because it was so large and many people would be able to stay there.

Also,

quite a few activities could be organized. During the construction and

modifications that I have already mentioned we stayed down in the

village. The

comrades who worked there slept in two houses. Enver and two other

comrades

slept in a small bungalow, which was a little down from the center,

where the

offices were. While I was staying in Helmes, I slept in the common room

of

Enver and his comrades. The landlady, Nuriham,

had two nice swarthy sons. They wore long shirts that reached and

covered part

of their legs because they did not have anything else to wear under it.

Nevruzi

who was four or five years old used to collect cigarette butts that the

comrades and partisans threw away and, wanting to imitate them, he

would

sometimes put one of them on his mouth and laugh. Enver lit a butt once

for him

and he nearly suffocated because of its smoke, so he never put them on

his

mouth again. He also has a photograph of this embarrassing moment with

the

cigarette butt on his mouth. We laugh whenever we see that photograph.

During a visit to

Skrapar, years after the Liberation, we saw that Nevruz had become a

Party

instructor. He looked different, was serious, handsome, neat and tidy

and was

wearing a suit. We were really glad to meet him again. We reminded him

of the

difficult days during the War in his house and the jokes we shared with

him. Of

course he didn’t remember many things, but we talked about what his

parents had

told to him.

When the first

buildings in the Lireza field were built, such as the kitchen and the

hut,we

went up there. Here the comrades of the youth leadership would work in

the

preparation for the Congress. Everything was built with timber and

planks taken

from the nearby forest, with the help of the peasants and some

partisans who

were skilled in these kinds of things. We stayed in a relatively big

hut. There

was a wide wooden bed above the floor in one part of it, in which we

would

sleep. Naturally, we couldn't even think about a mattress, but we were

able to lay

a piece of carpet or a hair-cloth down that the peasants had brought,

and we

used blankets that we had taken from the defeated Italian army as

covers. The

blankets were necessary up there in Lireza, because, although it was

summer

(late July, early August), it was really cool, especially at night. The

beautiful Lirez was enhanced even more when the delegates started to

arrive. If

only you could have seen that beautiful field. The tents looked like

white

flowers and, at night, were lit up by the partisan's fires. That field

bubbled

with the songs and voices of the youth who had come from all over the

country.

In this way, warming themselves by the fire, talking and singing, the

youth

often stayed up till the early hours of the morning.

This was

understandable because the majority of the delegates were partisans. It

was

their custom, after the long tiring marches, to get together at night

around

the fire, where they were able to relax and spend some precious moments

after

battling with the enemy. It was also a time to remember, to meditate

and honor

fallen comrades and family members who they had buried. That is why

their songs

were full of, not only grief, but also of optimism and the joy for the

future,

nostalgia and honor for missing comrades, and also their promise of

revenge.

These partisan songs, sung around these fires were, at the same time,

hymns for

the glory of the fallen, and also hymns for the faith and determination

to

accomplish the liberation of the country and the rebuilding of a new

Albania.

This is why my generation remembers with nostalgia, those partisan

fires. They

were marvelous moments that generated feelings of an inner happiness

for

everyone and for the special reason, that they were part of the big

war, the

war for Liberty, for the Motherland, for lofty human ideals!

Now, as I write

this in my dark prison cell, my eyes are fill with tears when I

remember the

bright flames of those partisan fires, which will be forever

remembered, not

only for me, but by all my contemporaries who were part of that

glorious time

of songs around the partisan fires. It is also memorable to those of

the

younger generations who keep alive the glorious work of the partisans

and

martyrs, who risked their young lives for Liberty. The attempts of

those who

try to distort and deny this glorious history of the National

Liberation Anti-fascist

War are failures and will not have a long life…

The blissful

environment in the unforgettable Lireza continued for nearly a month.

This was

because many delegates from the North arrived late due to the

difficulties in

moving around the country at that time. Many cultural activities were

organized; lead by our good comrade Pirro Kondi and some other comrades. A

Field

Radio was set up as well as a Press Table, where news, announcements,

literary

creations of the delegates such as poems, songs, caricatures etc. could

be read

by the youth.

While the

delegates were entertaining, singing and playing, we were working

without rest

for the preparation of the Congress, and not only for the Congress’

documents,

but also preparing and giving lectures to the youth on different

topics. We

were really pleased because the delegates were very interested in all

of these

matters.

After some days,

other comrades of the youth leadership in the field and in the partisan

brigades such as Liri

Belishova, Ramiz Alia, Alqi Kondi, Fadil Pacrami etc.,

arrived. We all joined the delegates. We sat and stayed with them,

talked,

played, sang and joked together because we were young and had the same

ideals.

There was nothing better than that populated Field with the flower of

our people,

with the brave and beautiful youth, who knew how to fight, to sing and

dance

and to learn about the preparations for the nation’s future.

I remember very

well the reception of Major

Ivanov, the chief of the Soviet military mission to

the General Headquarters of the Albanian National Liberation Army.

He had come from the Greek border, had crossed the Marta Pass, and went

down to

Helmes where the Headquarters was. The Albanian youth gave him a warm

reception

because they considered him as the representative of Stalin’s Red Army,

whom we

loved and admired for the defeats being caused to Hitler’s armies on

the

Eastern Front.

The anticipated

day, 8 August 1944, finally came. The Congress for the Union of the Albanian

Anti-fascist

Youth opened its proceedings. I, along with the other

participants,

still remember today that beautiful “hall” with no doors or windows,

built with

the timber that still emitted the fresh forest scent and with its roof

of fern

branches. The chairs for the delegates were made in a similar fashion,

with new

wooden planks taken from the forest, as was the long table of the

Presidium.

The pathway to the hall’s entrance was lined with lime painted stones.

A group

of young partisan boys and girls stood along the sides of the pathway,

with rifles

and submachine guns as honorary bodyguards. This gave a special

solemnity to

the entrance of the delegates to the Congress hall and to the beginning

of its

proceedings.

The hall

immediately became full of the lively voices of the youth, who were

very

enthusiastic and were not able to restrain themselves from singing and

cheering. Their enthusiasm was, however, indescribable when Enver Hoxha,

together with Dr.

Nishan, accompanied by Nako Spiro, came into the hall. Many

delegates

were seeing the commander for the first time. Some of them couldn’t

hold back

their tears of joy. Then, after the applause and ovations, silence

reigned in

the hall, until it was interrupted by Enver’s sonorous voice and his

passionate

words. He talked to the youth’s hearts as only he knew, touched the

delegates,

and made opened their eyes to the marvelous future that was waiting for

them;

Albania’s future and that of its long-suffering people.

The impressions

from this Congress are many. I remember I remember returning to Lireza

on the

45th anniversary of this memorable event. I found the Lireza field just

as

beautiful as I remembered, however, many of the delegates of that first

Congress in those unforgettable days, were not there for this

anniversary. Some

had died and some had not come because of old age, disease or some

other

inability. Even those who had come now had gray hair and were bent

because of

the years of war and hard work. But something had remained unchanged:

their

hearts and their souls were the same as they were 45 years ago. That’s

why when

we met together, along with the tears of nostalgia there was much joy

and cries

of happiness. Some remained embraced for a long time because they had

not seen

each other for decades. Each of them were reminded of those beautiful

days and,

in bringing back their memories, they behaved like those young boys and

girls

of 1944. They were very happy and spoke with honor and respect of each

other.

The organizers of

this meeting had tried to create the same premises as those of 45 years

ago

during the Congress; the wooden huts, the tents etc., whereas, the

“hall” of

the Congress was somewhat improvised. We experienced the same emotions

and

memories as then, but something was missing. Enver was not there, but

even

though he was not there physically, he was present at every moment and

at every

talk, because all remembered and talked about him lovingly, and, with

much

longing. In the evening the atmosphere was the same as during the

Congress,

because the partisan fires were lit, and around them boomed again the

beautiful

songs of the youth, intertwined with the beautiful songs of the people

from all

regions, south and north, since the participants came from all around

Albania.

There were not only some of the former delegates of the Congress, but

also

young school boys and girls, workers and peasants, who had given their

souls,

their zest and their joy to the Party. We looked at these young boys

and girls

and tried to follow their songs and dances, and, even though we were

old, we

felt young again amongst them. To tell the truth, while they stayed

near the

fires till dawn dancing, singing and joking, we elders took naps. It

was the

passionate youth to whom we had turned over the baton in order for them

to

continue this beautiful party, which has remained memorable to all of

us. Near

the end of the party I couldn’t help but go to visit Helmes. The

comrades

joked:

“You will go on

foot as then, or…?” “Aha

– I

said smiling – I can’t…”

There was now a

modern mountain road with many bends, which was needed in order to

utilize

forests in those parts. During the Youth Congress, there used to be a

goat

trail leading to Helmes, it was so steep that you could not walk

upright. But,

in those days, I flew from stone to stone because there was Enver who

was attracting

me like a magnet. I stayed there, alone for an hour with a gun in my

arm. Then

I walked up. I walked slowly, not because it was tiring, but because it

was

difficult to be away from Enver.

When I went to

Helmes now, after 45 years, I didn’t have my previous vitality. The

families

that used to live there had moved to new places. There were only two or

three

of the old houses remaining; those used as offices by the Central

Committee and

the General Headquarters and the house where Enver used to sleep. Going

around

these houses, the streets and under the shade of the trees, it seemed

to me

like I was witnessing a silent film. The silent and unvoiced view of

these

places could not bring back the happiness of those days; on the

contrary, it

created within me a grueling emptiness. Those who give life to a place

are the

people who live there.

But old friends

would never let you get bored. Old people, women and children came

towards me,

holding my hands, everybody wanting to take me in their house. It was

difficult

to choose where to go first. If I visited only one, the other would be

annoyed.

Those people who, during the war, gave us shelter in their houses,

risking

their own lives, giving us food and whatever they had, had great hearts

and

were very generous. I found these things again among these good and

friendly

people, who even now were doing what they could to please me. They gave

me

grapes, nuts, and delicious liquid honey in honeycombs. They had heard

I was

coming to the village and had cooked many things. They had also cooked

pancakes

to be eaten with the honey, and buns with fresh cheese, and many other

things.

After the

Congress, the chosen Secretariat

(Nako Spiro, First Secretary and

other members: Nexhmije

Xhuglini, Liri Belishova, Pirro Kondi, Fadil Pacrami, Alqi Kondi, Ramiz

Alia)

was called to a meeting by Enver Hoxha, who was the Secretary General

of the

Albanian Communist Party.

In my opinion

this was the most important meeting of the Youth leadership, for its

analysis

of the activities of the Communist Youth and also for the perspectives

revealed

by Enver for the future work of the organization of the Union of the

Albanian

Anti-fascist Youth. At the end of the meeting Ramiz Alia and I were designated to work with the

youth in the field and in the partisan units in the Central, North and

Northeast of Albania. On October 2nd, 1944, in Priske, the activists of

the UAAY (Union of the

Albanian Anti-fascist Youth) for South and Southeast Albania

gathered and there were 86 delegates. The meeting was successful

however; the

offices of the Nazi invaders were informed immediately about this

meeting.

Priska was hit by German field artillery, and the shells fell around

the house

where we were sheltered. This was often done by the Nazis who knew

where the First Corpus

Headquarters of the National Liberation Army (whose Commander was Dali

Ndreu and Commissar Hysni Kapo) was. Also located in the

same area

was a part of the British

Mission led by Smith.

In one of these shellings,

within the family of the patriot Hysen

Hysa (uncle Ceni,

who is immortalized so well

by Shevqet

Musaraj in “The National Front Epic”), 11 people were killed.

14.

In

Berat – Meeting with the Prime Minister

In the historical

liberated town of Berat I found an extraordinary enthusiastic and

joyful

atmosphere. The streets were crowded with partisans wandering in the

streets

that were full of citizens and many children. You could also see many

women

with black headdresses embracing the partisans as if they were their

sons.

I was taken to

the building where the General Headquarters was located, which, as I

was told,

was also the seat of the new Democratic

Interim Government, chosen a week

earlier, at the historical meeting of the National Liberation Anti-fascist Council.

During

the proceedings of that meeting, I was marching with the Congress

delegates

when I heard that the National Liberation Anti-fascist Committee had

been

reorganized into a Democratic

Government, and that, Enver was its

Prime Minister.

I am unable to

describe my feelings at that moment. I was very happy that our National

Liberation Movement, the war, the activities and sacrifices of our

people in

these years, under the leadership of the Communist Party, were being

crowned

with the creation of a new democratic power of the people and were

going

towards the final victory against the foreign enemy and their

collaborators. On

the other hand, seeing that Enver was given other high

responsibilities, I was

a bit worried and not too clear. This is something which I can’t

explain even now.

When I met and fell in love with Enver I had never thought he would

become

leader of the country and its prime minister, etc. I was worried and I

asked

myself this question:

“Would I be

worthy as his friend in life, in his work, and to the public…?”

The idea of this

responsibility burdened me, and made me feel insecure and skeptical

about

myself. A new complex was added to my timid nature; that of being a

responsible

and worthy wife for Enver Hoxha. I have to say that even 45 years after

our

marriage, I wasn't able to free myself of this complex. In everything

that I

did or wrote, I tortured myself because of this insecurity:

“Is it OK? How

can I improve it?”

It may seem

strange, but these emotions became even stronger when I had discussions

or I

had to speak in plenums, and in Congresses, etc. in the presence of

Enver. I

was afraid of bothering him or of raising issues with which he

disagreed. To

avoid this emotional feeling as much as I could, especially in solemn

moments,

I asked sometimes asked Enver to look over my speeches or I read to him

some

parts of it that I wasn’t sure of. Even though he was very busy he

seldom

refused the help I asked. As he was for everyone, he was a teacher for

me too,

anytime, and for anything.

When I arrived at

the location of the seat of the Democratic Party I saw that it was a

big house

that had been the house of feudalistic large landowners. Opening the

door of a

big room on the second floor they told me:

“This is Enver’s

room, stay here and relax until the Government meeting finishes. We

will inform

Enver about your arrival.”

The room was

small, simply furnished, well lit from a high window, and had white

curtains.

There was a bed in one corner; near it were a night table and an

antique

lampshade. Along the opposite wall were a desk, a chair and nothing

else. I

waited there for a while but I had nothing to do, so I went out into

the wide

hall, lit by some large windows. In the middle of hall was a large

heavy wooden

table. In the wood of this table were carvings of some mythical animal

images.

Near to the table were some big heavy doors. One of them was open and I

was

able to see the well-furnished room inside. I returned to Enver's room

and saw

that he had chosen one of the smallest and most simple rooms. I waited,

for

what seemed to me, an endless amount of time. It was three months since

I had

last seen Enver, when I left Helmes. At last the door opened and I saw

Enver.

He had put on a well-sewn military uniform. We hugged with longing not

wanting

to be separated. We were very happy. After a moment, I said suddenly:

“Congratulations

comrade Prime Minister…, but I liked those partisan shirts and breeches

more

and…when you were called Commander.”

We joked a bit

and then started talking about various and numerous problems. He told

me about

the developments at the National Liberation Anti-fascist Council

meeting, about

the decisions taken and the importance that they had for Albania, which

was on

the verge of liberation, and its future. I told him about the situation

in the areas

I had been and the work we had done.

After talking

about these things he took my hand saying:

“Come, I will

show you the house so you can choose a room.”

As I mentioned,

they were big, with curtains, rugs, heavy covers and furniture, which I

didn’t

like because they gave the rooms a medieval suffocating atmosphere. So

I said

to Enver laughing but hearty:

“I like your

clean and simple room...”

He laughed and

said: “I can understand that quite well........ It is getting near the

day when

we should have our own house…”

The following day

I went to the offices where the comrades who had arrived early for the

organization of the First

Congress for the Union of Albanian Anti-fascist Women

were situated. Comrades such as Liri

Gega, Naxhije Dume, Fiqret Sanxhaktari etc.

Four partisan comrades from Yugoslavia had come to take part in this

Congress.

They had grades and were wearing smart military uniforms. Their

appearance was

much better than that of our partisans, who were no less brave, but did

not

have any grades.

Liri invited me

to meet the guests in the Yugoslav military Mission. There I was

introduced,

for the first time with the new representatives of the Mission, Velimir Stojnic and Niaz Dizdarevic.

I knew that

Dushan Mugosha had left Albania and at the request of Koci Xoxe

we wrote some letters of greetings to him, but I didn’t know that Milan Popovici

had also left. During my visit I noticed that the Yugoslav Mission resembled an inn

without gates, where our comrades came and went as they would in their

own

houses. It had become a club for meeting and talking. This impressed me

a lot.

When I got back

home I asked Enver immediately about Miladin. He said that he had left in a

very

depressed state because the new comrades who came to the mission had

criticized

his work in Albania with regard to our Communist Party. They had said

that the Central Committee

of the Yugoslavian Communist Party had decided to remove

them from

Albania and that they had come themselves as substitutes him and Dushan

in

their relationship with our Party. They would also perform the official

function as representatives of the Yugoslavian Military Mission like

the

British, Soviets and Americans during the war. While talking with Enver

I told

him that, like many comrades, Liri

Gega also went frequently to the Yugoslav

Military Mission even though they didn’t have any important duties to

complete,

and that they behaved as if they were in their own houses. Making no

comments

Enver said:

“They can do

whatever they want, but you do not have anything to do there…”

I was impressed

by the way he said that. From his tone you could feel discontent and

disapproval. But while I was in Berat, I wasn't aware of what was

happening

around him and against him, in the background.

On November 4th,

the First Congress

of the Union of Albanian Anti-fascist Women was opened. All

the

preparations had been made by Liri

Gega and Naxhije Dume.

I was not called upon

to view the documents, nor was I to be presented with the

organizational

measures, even though I had been appointed as a supervisor of the

commission

that the First National Conference set up for the organization. This

was, I

thought, because I had come late to Berat. These comrades did not

inform me or

call me to come to the Congress and I thought that this was

unintentional

because of the difficulties of communication in this time of war. If I

hadn’t

received Enver’s letter in which he wrote: “See you at the Women’s

Congress…” I

wouldn’t have gone to Berat and I wouldn’t have taken part in the

Congress, because

I wouldn't have known about it. I received another surprise when the

Congress’

bodies were chosen. I was not proposed to be in its presidium, but I

was

appointed, along with comrade Vito Kondi to the Congress’ secretariat.

I

decided not to bring all these matters to the attention of Enver.

Enver did not say

a word to me about what was happening in Berat. I am unable to say if

he did

this so that I would not be worried, or to respect the principle that

the

affairs of leadership affairs were things that should not be discussed

with

one's wife.

Being at that

time a member of Central

Committee of the Communist Youth and

of the

Secretariat of the Union of Albanian Anti-fascist Youth, I

remarked

to Nako Spiro

that, it had been a long time since we had held a meeting; perhaps,

because

like me, some of the comrades had been kept very busy since the Youth

Congress

in Helmes…

Nako stood up and

invited me to walk with him alongside the river. We walked in silence

for some

time. Apparently he didn’t know how to begin.

During our walk

along the Osum bank, he finally broke his silence and said:

“Well, you are

not going to work with the youth anymore…”

Greatly surprised

by this sudden news, I interrupted him and said:

“How come? Now we

are on the verge of Liberation I can hardly wait to get back to Tirana

to work

with the Youth…. When was this decided?”

I was continuing

to speak in this manner, rather hastily and somewhat upset.

“Just a minute,”

he said, “The Central Committee has decided that you should take part

in the Ideological

Commission at the Central Committee of the Party, led by Sejfulla Maleshova.”

Then he told me

about the importance of this commission, but I was getting angry with

Enver

too, because he hadn’t told me anything about this change. When

returned to the

seat of the new Government and General Headquarters, I told Enver what

Nako had

said to me. Enver tried to calm me down, telling me about the functions

of this

commission, its relationship to the Central Committee, and, at the same

time,

that it was part of the Ministry of Culture, whose minister would be

Sejfulla,

and I would deal with Tirana Radio, education etc.

The treatment I

had received at the Women’s Congress and this sudden news left a bitter

taste

in my mouth, but at that time I did not understand why they were

happening,

because no one, not even Enver had told me what was going on backstage

in

Berat. Later, everything became clear. Apparently, they wanted to leave

Enver

out of the State and Party leadership, and they didn’t want to have me

among

them informing Enver of their actions against him.

15. Capital

Liberation. The new Democratic Government in Tirana

On 17 November 1944, after 19 days of

violent

fighting, we got the long-awaited news of the Liberation of Tirana. We

were

very happy that day. While Enver was greeting the partisans and the

people in

the yard from the window of the Seat of the General Headquarters, I

went to his

room, locked the door and cried for all the dead comrades, remembering

each one

of them. Some were killed heroically in fighting at the barricades;

some were

massacred, hanged or tortured. It seemed unjust that they were not

there, that

they were not alive celebrating and enjoying this victory. Although I

didn't

swear an oath at that moment, I have never forgotten those strong

feelings of

love and pain that I felt on that day. Not even when I was tired, when

I was

facing difficult moments, including these tough years of loneliness in

prison,

and my old age. I have told myself:

“That’s OK. Their dreams for the

liberation of the

nation were realized, and I will continue fighting for those friends of

mine

who were killed during the struggle and will die with honor, like them.”

The day after we got the wonderful news of

the

liberation of the capital, Fiqret

Sanxhaktari (Shehu) came to Enver and

asked permission to go to Tirana. Since the fighting had ended, she

wanted to

be near Mehmet

because she had become engaged to him in Permet, during the Congress. Giving her permission, Enver turned to me and

said:

“Nexhmije, why don’t you go along with

Fiqret? I will

be very busy here, so meanwhile, you can stay with your parents,” he

added

laughing, “because it is getting near the time we will be going to our

own

house.”

So I decided to leave Berat.

We set off in a mille cento car. A comrade

came with

us. I remembered that the Ura Vajgurore bridge or whatever it was

called at

that time was completely destroyed, so we crossed the river by raft.

From the

Krraba Pass until we arrived in Tirana we past many smoking burnt-out

tanks. We

also saw quite a few German corpses. We arrived in the centre of Tirana

at

Skanderbeg’s square, and decided to take walk in order to see how badly

our

capital had been damaged and also because we had missed it a lot. What

I

noticed immediately was the beautiful minaret of the mosque near the

clock

tower. Only half of it remained because a shell had damaged it.

The Germans had built a bunker in the

centre of the

square where all the streets intersected. It was nearly level with the

ground,

with holes for looking out or to put the muzzles of the machine guns

through. I

wasn't able to see the entrance for the soldiers because it seemed too

narrow

to enter from above. Perhaps they had built a tunnel under the square,

connected to the town hall, which stood where the National Historical

Museum is

today. It was said that in this bunker, the enemy had put up a strong

resistance, and had killed and injured many partisans, who had bravely

attacked

that bunker in the middle of the capital. Finally it was captured, and

one of

our artists had painted a picture of the victorious partisan on the

wall of the

bunker, as a memorial to their courage.

In Royal Street, now called Barricades

Street, you

could see the rubbish left from the harsh war fought in that streets –

as I was

told – by the guerilla units, in cooperation with professional partisan

teams,

and helped by young volunteers and anti-fascist women from Tirana.

I left Fiqret in Bami Street, later called

“Qemal

Stafa”. I hastened to my house, in Saraceve Street, thinking to

surprise to my

parents. But they weren’t there! They hadn’t yet come back from the

free areas,

where they had had to go with my sick brother. He was an underground

activist.

They left Tirana when they heard the news that they were to be

arrested. As I

was later informed, my house had been searched seven times, often under

the

direction of Man

Kukaleshi, the number one in the Qazim Mulleti. The reason for these

searches was that there had been a report of a spy living in our alley,

who had

said that we had a radio transmitter in the house. Maybe he had noticed

the

activities going on with the people who exchanged letters,

communiqués, and

leaflets, etc. with my mother. And also, many who stayed there, such as

the

couriers of some districts used the house as their base, as I have

written

earlier.

As I didn’t find anyone at home, I headed

towards the

house of Enver to surprise his parents. They lived in a bungalow with

two rooms

with view of the ring road, opposite Bije Vokshi’s house, where the Albanian Communist

Youth Organization had been established. I entered the house

happily

and when they saw me they were really surprised and very pleased.

Immediately

they asked me numerous questions about Enver. The father, uncle Halil, was interested in

knowing about the new Government which had been created in Berat, and

also

about the ministers, some of whom he knew, because they were from

Gjirokastra:

such as Dr

Nishani and others.

One time Ane said to her husband:

“Why don’t you tell the bride what that

frontist said

about the Government?” “Come on, forget that bastard,” he responded

angrily.

It was understood that he didn’t want

others to

remind him of that frontist so he didn’t talk about it. As I was told

later a

former friend of his from Gjirokastra, who was a frontist now, had told

uncle

Halil ironically:

“Have you heard Halil, Enver has become

the Prime

Minister of the new Government”. “

“He has done his best,” uncle Halil had

responded,

“Don’t you like it?”

“Heh,” said the frontist on leaving, “a

mountain

Government, a wet Government…”

That’s why uncle Halil was angry. But the

frontists

and their friends have now seen for 45 years what this mountain

government is

and what it could achieve. They have tried for so long to destroy it

but they

can’t take from the people’s souls the conviction about the benefits

that the

government brought to the country…

Now the liberated Tirana would wait for

the new

Democratic Government to come from Berat. The long-awaited day came.

The

government arrived in the capital on November 1944. It was a nice

November

morning, when all the members of the Government leads by Enver, arrived

in the

square between the ministries and walked to the Dajti hotel where, in

front of

the hotel steps was placed a simple tribune decorated with flags and

laurels.

The inhabitants of the capital were overwhelmed with an indescribable

enthusiasm. The partisans helped to give the atmosphere a sense of

great

liveliness. They had fought for the liberation of Tirana, felt proud of

their

deeds and celebrated by singing partisan songs.

A group of martyrs’ mothers went up to the

Government

members. The moment when these mothers embraced Enver and the other

members as

if they were their sons was very touching and moving. They wished them

heartily:

“May you have

a long life…may free Albania have a long life!”

then the mothers sat in front of the

tribune where

there were many people waiting impatiently to see the leaders of this

new

democratic state. Among them were a group of young women dressed in

beautiful

and varicolored national costumes. One of them was holding a red flag

with the

sublime eagle in the middle. Below, at the side of the Avenue’s bridge

over the

Lana River, were lines of partisan battalions who had taken part in the

Liberation of Tirana. They were to parade in front the members of the

Government and the General Commander, Enver Hoxha.

The moment came when the members of the

Government,

of the National Liberation Front Leadership and of the General

Headquarters

reached the tribune. Enver

Hoxha, Dr. Omer Nishani, Myslim Peza, Haxhi Lleshi,

Baba Faja Martaneshi; Mehemet Shehu, Medar Shtylla and

others were

presented to the cheering and applauding crowds. Along with some

comrades, I

watched the ceremony from the balcony of the Dajti Hotel.

From the tribune in front of the cheering

crowd,

Enver Hoxha delivered his first historical speech before the people of

Tirana.

In his speech as the Prime Minister of the Interim Democratic

Government in

Berat, Enver had issued the call:

“More bread! More culture!”

Whereas in his speech in the liberated

capital, among

other things he said:

“Today opens a new page in our history,

and it is up

to us to make it as glorious as our war against the occupier. This will

be a

war for the reconstruction of Albania, a war for the boosting of the

economy,

for the increase in the cultural and educational levels of our people,

for the

progress of its political, economic and social levels… Let the whole of

Albania

become a building site, where young and old people understand they no

longer

work for foreigners, but for themselves and the construction of their

own

country . . . No honest Albanian citizen should remain out of the

Front. On the

occasion of the 28th November festival, on the occasion of the

liberation of

Tirana, the leadership of the Albanian Antifascist National Liberation

Council

gives a general amnesty to all the members of the National Front,

Legaliteti

and other organizations who were cooperating with the occupier. From

this

amnesty are excluded all the war criminals who have killed, burnt,

dishonored

or stolen the people’s wealth.”

The people looked at the leader carefully,

the

Commander, for whom they had heard so much during the war. They

followed him

with an unseen enthusiasm. Together, with the people of the suffering

population and who were broken by the war, but whose eyes sparkled

because of

the joy of freedom and the presence of the members of the Government,

had come

some of the defeated, who, with the end of the war, had lost political

and

economic power.

I remember that during the ceremony, when

the leaders

of the state mounted the tribune, a rather ridiculous incident

occurred. We saw

that on one side of the tribune there was a former minister of Zogu, Ferit Vokopola,

and also a merchant from Tirana, Ali

Bakiu. I knew both of them. In the merchants

shop we used to buy notebooks and other school items. I had also bought

a

violin there, because this was wanted by every student preparing to

become a

teacher. The former minister was the father of one of my classmates.

When the

organizers of the ceremony saw them both they laughed but became

somewhat

concerned as well. Actually, the merchant from Tirana was allowed to

stay

because he had helped the National Liberation Movement; he was an

anti-fascist,

whereas the former minister left the tribune after they told him

politely that

his place was not there.

On the occasion of the arrival of the new

Government

in the liberated Tirana, in the evening of the 28th and 29th of

November a

large reception was organized in the Dajti Hotel. In addition to the

new

authorities, of the Government and the Front etc., there were

Commanders,

Commissars, and distinguished partisans from the battles with the Nazis

and

Fascists long with martyrs’ mothers and relations. All the Allied

Missions in

Albania were invited, the British, Soviet, American and Yugoslav.

At this reception, for the first time, I

was with

Enver, making our matrimonial relationship official. The main

authorities of

the country and the foreign guests sat in one corner of the big hotel

hall. In

the middle of it, where we were, and in all the other halls of the

hotel,

people sang and danced with uncontrolled enthusiasm.

All the members of the allied missions

were enjoying

themselves, especially those of the British Mission who were represented

by quite a

few. At this time it was their right to be happy. For months they had

wandered

in the mountains, sleeping in towers and Albanian huts, far from their

families

and living under the terror of being bombed by Nazi planes. They looked

a bit

ridiculous but it was also very nice - when they joined in our southern

folk

dances dancers and tried to move their legs as we did. Of course they

wanted to

dance the modern dances, as well; the tango, waltz etc. but most of

those who

were in the hall had come from the mountains, and those young partisans

knew

that those dances were not appreciated by the general population at

that time.

One of the British officers thought that Madam Hoxha knew one of these

couple

dances, and, according to the rules, asked permission from Enver.

Unfortunately, I had never danced that kind of dance so I felt really

embarrassed until the music ended.

In the corner where we were sitting, Enver

and Dr.

Nishani engaged a representative of the British Mission to see if he

could

handle Albanian raki. They themselves drank two glasses for the big

festival

and then told the waiter to fill them with water. So while they were

drinking

water, the Englishman was drinking raki until he was completely drunk,

and

everyone started laughing heartily. The guest tried to hold his liquor

but, in

the end, he vomited. While he was vomiting Dr. Nishani made one of his

sarcastic comments: “The Englishman vomited the colonies.”

It is a well-known fact that after the

Liberation,

the relationships of our state leadership with the allied military

missions

were close and correct, and not only with the Soviet and Yugoslavian

mission

but also with the British representatives but somewhat less with the

Americans,

whose rank was lower. The United States had thought it would be

“reasonable”

that their emissaries should be of Albanian origin, failing to predict

that the

local Albanians would not put up the haughty advice and interference of

these

Albanians, who were rather pompous and came from over the ocean.

Enver as the leader of the new Government

and Foreign

Minister, taking me with him, decided to make some goodwill visits to

the

allied missions. I remember the visit to the British Mission chief, Jacobs. The

Mission was located in a villa between “Qemal Stafa” stadium and the

now

Albanian Television Station. He was a good host to us. They served

their famous

tea and biscuits. At that time we had serious problems with the western

allies

in such matters as the recognition of the Government, the upcoming

elections,

the conditions for the UNRRA aid etc. As far as I remember, we didn’t

mention

these problems during this visit, because they might have caused some

irritation to our relationships. We discussed the role of the allied

missions

during the war, about the British Mission and their members who had

been in

Albania and near the General Headquarters. Enver talked about them and

Jacobs

told us where some of them had now moved on to other missions; to Egypt

near

the Mediterranean Allied Headquarters, to Italy, and, in some cases,

back to

England.

In the second half of 1991, when my

children and I

had left our house and were settled in a flat, two English journalists

came to

visit me. At that time I didn’t wish to receive journalists, but they

informed

me that they had a “last will” from a former officer of the British

Mission

during the National Liberation War. I became curious so I accepted

their

request. One of them was a journalist, the other a photo reporter

working for “The Sunday Times”.

The journalist took from his pocket and showed me a photo of a young

officer,

who, as he told me, was his father, a former member of the British

Mission in

Albania during the war. This man, as his father had told him, had

jumped with a

parachute somewhere near Elbasan (maybe in the Biza field where the

allies dropped

supplies), but while landing he had been hurt and had been sent to a

partisan

hospital. According to them I had helped him and I had given him a

toothbrush.

His Dad had told him about the life in Albania, the partisan's war and

had told

him that he had been at the dinner party in the Dajti Hotel for the

wedding of

Enver Hoxha and myself. Before dying he had told his son to visit to

Albania

and to come and thank me, and as a souvenir he gave me a toothbrush,

new of

course.

His father had confused me with someone

else, but I

couldn’t disappoint his son, so I said: “…Thank you...” and some other

friendly

words about the Englishmen I had known in Elbasan, Berat, Helmes etc. I

also

told him that we did not organize a dinner for our wedding at the Dajti

Hotel,

but that it had been a welcoming reception to celebrate the new Democratic Government in the

liberated

Tirana, and I told him playfully that maybe I had danced with his

father.

When I was sent to prison, I read a small

newspaper

from our foreign friends and also saw the photographs of these two

friends of

Albania with some others. They had organized a demonstration with

placards

etc., demanding my release, in front of a building where there was a

delegation

of the Sali Berisha Government.

16.

Our partisan wedding

When the new Government came to Tirana,

the majority

or, better to say all of its members, stayed in the Dajti Hotel. Enver

had a

bedroom with an anteroom. I remember staying there all December, until

the

relevant offices were set-up, and we got our house. We were given a

house in

New Tirana, on “Ismail Qemali” street. It had been the house of an

engineer or

director of the “Belloti” firm. We lived

there for 30 years.

Enver and I decided to hold our official

wedding on

the New Year Eve (1944-1945), and we told our families this. They were

surprised and said: “Wait a minute, we’re not ready!” We told them that

we

didn’t want a wedding ceremony or anything special. In fact, our

families were

correct because they finally had an opportunity to marry off their only

son to

me, an only daughter. That is why they insisted that we should

celebrate twice,

because we had survived the war. Enver said:

“Many young comrades like us were killed

in the war

that is why we can’t have a wedding ceremony”.

So they had to accept our partisan

wedding.

Nevertheless they did manage to do something.

On the 30th of December my family invited

the family

of my uncle to dinner, Arif

Xhuglini, and his children. I remember that,

after dinner, my uncle’s wife took me aside and wanted to tell me about

the

mysteries of the first night of the wedding, as it had been done to

her. As she

started talking I felt very embarrassed so I interrupted her saying:

“No, no I don’t want…” and left.

It seemed banal to me to stay and listen

those

things, maybe I felt ashamed at that time. Later when I became more

interested

in traditions and social customs and it also become part of my job, I

said to

myself:

“Why didn’t I let her talk in order to

better

understand the knowledge and concepts existing then about the

relationship

between man and woman?”

Because, I think that, the simpler the

people from

the cultural point of view, the more simplified are these intimate

relationships. This doesn’t mean that simple people do not fall in

love, do not

have passions, what I mean is that, along with the expansion of the

cultural

horizon, intimate relationships “get complicated”, are cultivated and

smartened

up more than nature has given to us humans, more than nature has given

to the

animals, and much higher than the natural instinct of every living

being to

breed.

Something nice happened the following day,

on

December 31st. in the morning, when some members of Enver’s family had

come to

take the “bride”. They were Enver’s sisters Farihe and Sano. We waited on them hospitably

and treated them with different kinds of sweets, according to the

custom. We

laughed very much when they told us what Enver had done:

“We asked him to give us his car, but he

wouldn't