ALLIANCE 17:

October 1995

REVISIONIST ECONOMICS IN THE USSR

Part one: Eugene Varga

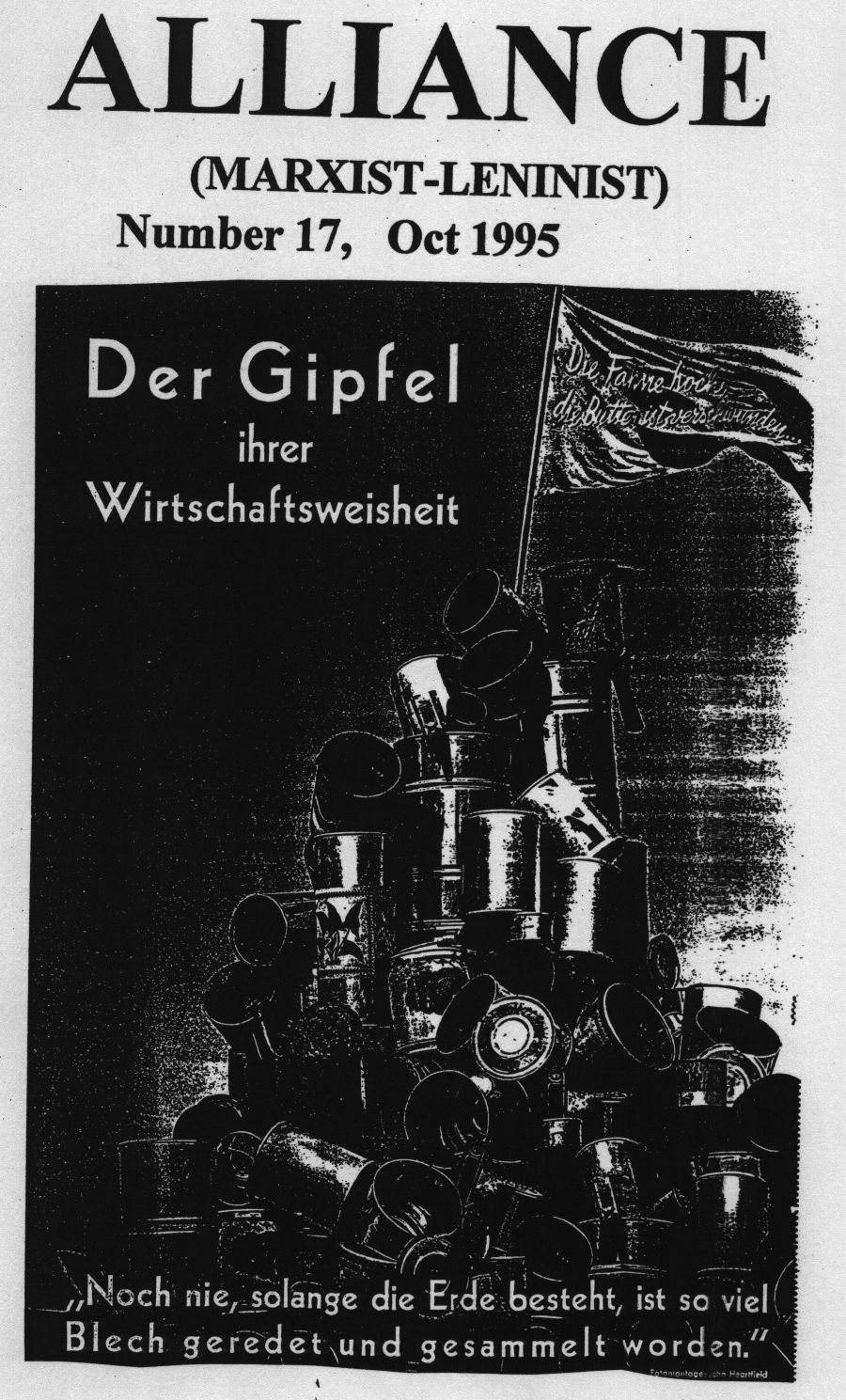

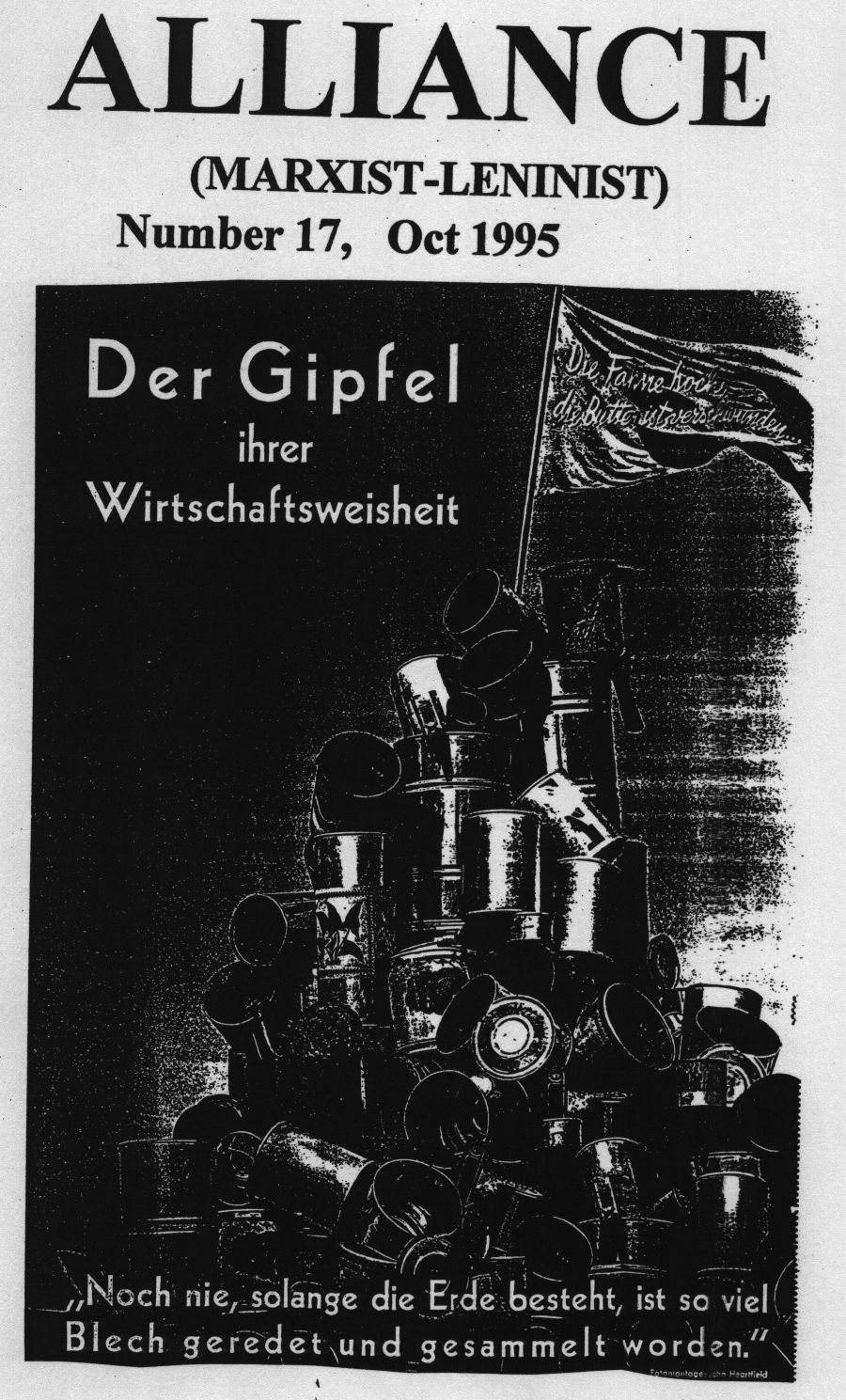

COVER

Alliance 4, reprinted some pioneering photomontges of JOHN HEARTFIELD (1891-1968). This

is another example.

Originally Helmut Herzfeld, this artist put his talents to aid the world's working class.

Under German fascism, he deliberately adopted an English name. He worked as a member, for

the German Communist Party. His hard hitting satires drove home the messages to German

workers; that fascism and Hitler was their worst enemy.

This 1937 poster is entitled

"The Pinnacle of their economic wisdom".

On the flag is written:

"Raise the flag, the butter has disappeared".

At the bottom of the empty tin cans is written:

"Never since this world existed has so much empty talk

been spewed out and collected".

AS MUCH CAN BE SAID OF REVISIONIST AND BOURGEOIS ECONOMIC THEORY.

EDITOR'S INTRODUCTION

This issue of Alliance North America concerns revisionist economics. Economics is often a

confusing topic. But Marxist-Leninists need to understand some of the technicalities.

Why? Because the bourgeoisie uses technical "froth" to disguise the essential fact - exploitation.

In the USSR, this disguise, was aimed at undermining Marxist economics with revisionist theories.

After Stalin's death, it succeeded.

Previously Alliance has discussed both modern day economic issues (See Alliance 3 on

inflation versus deflation; and protectionism etc); and economic revisionism.

The relation of economic revisionism to the confusion following the death of Stalin, has been e

xtensively discussed in Alliance.

Comrade Bland (Communist League - UK) showed, that the economic measures proposed and enacted

by Khrushchev, were first proposed by Vosnesenky and defeated by Stalin

(See Alliance Number 9 : reprint `The Leningrad Affair').

Stalin correctly foresaw that the implementation of these proposals would lead straight to

capitalism.

Hence the title of Bland's book : "The Restoration Of Capitalism In the USSR"

(See reprint Alliance 14).

In order to further understand how revisionism spread its tentacles - we re-print some work of

the Marxist-Leninist Research Bureau (UK), published in 1995. This was written by Bland, and details

the rise of revisionist economics in the USSR.

The two revisionists analysed here, are EVGENY VARGA and NIKOLAY VOSNESENSKY.

The latter has been remarked upon in Alliance before, but this report carries more detail.

Finally we make a brief announcement.

Shortly we will be publishing an "Open Letter"; that deals with some current confusion about

the pseudo-Left revisionism of Mao Ze Dong.

Please note:

The designation * by a name, signifies that Bland has written a short biographical

not,to be found at the end of the article.

MARXIST-LENINIST RESEARCH BUREAU Report No 2

THE REVISIONIST ATTACK ON MARXIST-LENINIST ECONOMICS

1: EVGENY VARGA

Biographical Note (to 1947)

Eugeny (Jena) Samilovich Varga* was born in Hungary in 1879. After graduating from the University of Budapest, he joined the Hungarian Social-Democratic Party in 1906 and became a member of its central executive. In 1918 ha was appointed Professor of Political Economy at the University of Budapest, and in March 1919 he became People's Commissar of Finance, and later Chairman of the Supreme Council of National Economy, in the Hungarian Soviet government. After the overthrow of that government, he went to Austria and in 1920 to Soviet Russia, where he became (as the 'Times' expressed it in his obituary)

"�.the leading economic theorist of the Soviet Union and the Communist world".

('Times', 9 October 1964; p. 15).

In 1922 he was sent to Berlin as head of the Soviet trade delegation. At this time he made no attempt to disguise his Trotskyist views:

"While he stayed at the Berlin Embassy, Trotsky* spent many hours in discussions with Krestinsky*. the Ambassador, and E. Varga, the Comintern's leading economist. The subject of his discussions with Varga was socialism in a single country".

(The Trotsky Archives, Harvard University, cited in: Isaac Deutcher: 'The Prophet Unarmed: Trotsky: 1921-1929'; Oxford; 1959; p. 266).

Varga maintained

�. . . that as an economic theory, Stalin's doctrine was worthless". (The Trotsky Archives, Harvard University: ibid.; p. 266).

From 1926 to 1932, he was chief editor of the Communist International journal 'International Press Correspondence'.

In 1927,

�. . . he was criticised for theoretical deviation".

(Branko Lazitch Milorad M. Drachkovich: 'Biographical Dictionary of the Comintern'; Stanford (USA); 1973; p. 425).

In 1930 he was elected to the USSR Academy of Sciences. On his return to the Soviet Union, he was made director of the Institute of World Economy and World Politics, which in 1936 was incorporated into the USSR Academy of Sciences.

Varga's Book on War Economy (1946)

In September 1946 a book by Varga was published in Moscow entitled 'Izmenlya�'v Ekonomike Kapitalizma v Itoge Vtoroi Mirovoi Voiny' (Changes in the Economy of Capitalism as a Result of the Second World War).

(A summary of the content of the book appears in: Philip J. Jaffe: 'The Rise and Fall of American Communism'; New York; 1975; p. 103-05).

It incorporated a number of features and theses diverging from long accepted Marxist-Leninist principles, namely:

1) instead of dealing with economic and political questions together and revealing their interrelation, it dealt in the volume published only with 'economic questions, stating that political questions would be dealt with in a later volume;

2) it declared that 'state capitalism' prevailed in the People's Democracies established in Eastern Europe after the Second World War and that these states were of 'relatively small significance in world economy';

3) it presented the state in monopoly capitalist countries as the machinery of rule of monopoly capital only 'in normal times', while in times of national emergency, such as war, it was 'the machinery of rule of the capitalist class as a whole';

4) it fostered the view that nationalisation measures in modern capitalist countries were 'analogous to the measures carried out in the People's Democracies of Eastern Europe';

5) it fostered the view that, in modern capitalist countries, the working class 'could gradually increase its influence in the state apparatus until it had secured the dominant position within it';

6) it painted a picture of relations between modern imperialist countries and colonial-type countries which implied that the former relations of dominance and exploitation of the latter by the former had been 'reversed';

7) it expressed the view that the wartime changes in modern capitalist countries made 'state economic planning' possible in those countries;

8) it did not base itself on the theory that the general crisis of capitalism was deepening.

9) it expressed the view that in the post-war world the contradictions between imperialism and the Soviet Union would be 'greatly reduced', so that Lenin's proposition that war was inevitable under imperialism was no longer valid.

The Criticism of Varga's Book (1947-49)

In May 1947, the book was strongly criticised at three sessions of a joint conference of the Political Economy Sector of the Economics Institute and of the Political Economy Faculty of Moscow University:

'"Varga's book was subject to extensive criticism in a series of specially convened meetings of the Economics Institute of the Academy of Sciences and the Economics Department of Moscow University on May 7th, 14th and 21st 1947".'

(R. S.: 'The Discussions on E. Varga's Book on Capitalist War Economy", in: 'Soviet Studies', Volume 1, No. 1 (June 1949); p. 33),

Although

. " . the May Discussion . . . was conducted in good spirit and in a dignified manner". (Evsey D. Domar: 'The Varga Controversy', in: 'American Economic Review', Volume 40, No. 4 (March 1950); p. 149).

However, at this time Varga was willing to make only one minor admission of error -- on the character of the People's Democracies':

"If you were to ask me whether I consider it necessary to change any theoretical proposition . . . (except the treatment of the question concerning the character of people's democracy) I would have to reply, comrades -- 'No". And those reviews that I have seen also have not convinced me in the slightest that any of my fundamental theoretical propositions need changing".

(�Soviet Views on the Post-War World Economy: An Official Critique of Evgeny Varga's "Changes in the Economy of Capitalism resulting from the Second World War"; Washington; 1948; p. 2-3).

Five months later, in October 1947,

" . . . Varga's Institute of World Economy was liquidated"

('A Soviet Economist Falls from Grace', in: 'Fortune', Volume 37 (March 1948); p. 5).

In October 1948,

�an augmented session of the Learned Council of Academy of Sciences with the participation scholars, educators and representatives of government ministers, convened".

(Philip J. Jaffe: op. cit.; p. 111-12).

The main item on the agenda was a further critical discussion on Varga's book.

Konstantin Ostrovitianov*, the director of the Economics Institute of the USSR Academy of Sciences, made a strong criticism of Varga (as well as of those who had worked under his direction), in particular for their failure fully to admit their mistakes:

"The series of works published in recent years on questions of the economics and politics of capitalist countries contain gross anti-Marxist errors and distortions. . . .

Thew books were severely and justly criticised in the pages of the Soviet press. The criticism revealed systematic errors of a reformist nature in these books. . . .

Mistakes of a reformist nature also found reflection in the magazine 'World Economy and World Politics', of which Varga was editor.

Comrade Varga, who headed this un-Marxist trend, and some of his fellow-travellers, have not yet made admissions of their mistakes. . . . Such non-Party attitude towards criticism leads to new theoretical and political errors".

(Konstantin Ostrovitianov: 'Concerning Shortcomings and Tasks of Research Work in the Field of Economics', in: 'Current Digest of the Soviet Prams', `Volume 1, No. 6 (8 March 1949); p. 5-6).

Varga still, however, refused to admit more than two errors in his work:

"The separation of economics from politics was erroneous. . . . "

I erred when I said that state capitalism prevailed in the economy of the people's democracies. . . .

I cannot follow the advice and admit all the criticisms of my work to be correct. This would mean that I am deceiving the Party, hypocritically saying: 'I am in agreement with the criticism' when I was not in agreement with it. . . . There are things I cannot admit".

(Evgeny Varga: Contribution to 'Reports and Discussions concerning the Shortcomings and Tasks of Research in the Field of Economics, Augmented Session of Learned Council of the Economic Institute of the USSR Academy of Sciences, in: 'Current Digest of the Soviet Press', Volume 1, No. 11 (12 April 1949); p. 17, 18).

In closing the discussion, Ostrovitianov commented:

"Comrade Varga continues stubbornly to deny his gross errors of principle which were characterised in our Party press as mistakes of a reformist nature. . . .

You are asked to abandon the part of an injured dignitary of science and to try conscientiously to analyse your errors and, most important, to correct them, creating new works corresponding to the requirements of Marxist-Leninist science. From the history of our Party, you should know to what sad consequences stubborn insistence on one's errors leads".

(Konstantin Ostrovitianov: Concluding Remarks in Discussion 'Concerning Shortcomings and Tasks of Research Work in the Field of Economics', in: 'Current Digest of the Soviet Press', Volume 1, No. 12 (19 April 1949; p.5-6)

Varga's Disclaimer (1949)

However, as most his colleagues came to accept the strong criticism levelled at Varga's ideas, in March 1949 Varga felt compelled to write a letter to the Communist Party newspaper 'Pravda' (Truth) denying foreign press reports that he was 'of Western orientation':

"I wish to protest most strongly against the dark hints of the war instigators to the effect that I am a man 'of Western orientation'. Today, in the present historical circumstances, that would mean being a counter-revolutionary, an anti-Soviet traitor to the working class".

(Evgeny Varga: Letter to the Editor, 'Pravda' (15 March 1949), in: 'Current Digest of the Soviet Press', Volume 1, No. 10 (5 April 1949); p. 45).

Varga's Self-Criticism (1949)

In April 1949, Varga published in 'Voprosy ekonomiki' (Problems of Economics) a long article admitting the justice of the criticisms made of

his book, accepting responsibility for mistakes in other works published under the auspices of the Institute of World Economics and World Politics, and regretting that he did not accept the criticism earlier:

"My book 'Changes in the Economy of Capitalism as a Result of the Second World War' was severely criticised, as is well known, in the Party press and in scholarly discussions. A large number of other works of the former Institute of World Economy and World Politics, published after the war, likewise were severely criticised. As director of that institute, I was responsible for these works. This criticism was necessary and correct. . My mistake was that I did not recognise at once the correctness of this criticism. But better late than never. . . .

My prolonged delay in admitting the mistakes disclosed by the criticism undoubtedly was harmful. . . .

Honourably to admit mistakes made; to analyse their causes thoroughly in order to avoid them in the future -- this is precisely what Lenin considered the only correct approach, both for Communist parties and for individual comrades. . . .

There is no doubt that in this respect I did not act with wisdom".

(Evgeny Varga: 'Against the Reformist Tendency in Works on Imperialism', in 'Current Digest of the Soviet Press', Volume 1, No. 19 (hereafter listed as 'Evgeny Varga (1949)'; p. 3, 9).

Varga admitted that these errors were particularly dangerous because they were reformist departures from Marxism-Leninism:

"These errors constitute a whole chain of errors of a reformist tendency, in toto signifying a departure from a Leninist-Stalinist evaluation of modern imperialism.

It goes without saying that mistakes of a reformist tendency also signify mistakes of a cosmopolitan tendency, because they paint capitalism in rosy colours.

Every reformist mistake, every infringement of the purity of Marxist-Leninist teachings, is especially dangerous in present historical circumstances".

(Evgeny Varga (1949): ibid.; p. 3).

and because they related to the evaluation of the nature of the bourgeois state:

"All mistakes of a reformist tendency in respect of the bourgeois state . . . lend support to the counter-revolutionary, reformist

deception of the working class. . . .

The mistakes in my book, disclosed by the criticism, have all the greater significance in that they principally concern questions on the evaluation of the role and character of the bourgeois state".

(Evgeny Varga (1949): ibid.; p. 3, 4).

Varga agreed with his critics that the fundamental reason for his chain of reformist errors was his incorrect attempt to separate economics from politics:

"The fundamental reason for this (chain of errors -- Ed.), as my critics correctly established, was the methodologically erroneous

separation of economics from politics. . . .

Mistakes of a reformist tendency inevitably proceed from a departure from the Marxist-Leninist dialectical method, which demands a many-sided study of all phenomena under analysis and their mutual relationships. . . .

When an attempt is made, (as in my case and that of a number of other authors of the former Institute of World Economics and World Politics) to analyse the economy of capitalism 'outside of politics', this departure from the Marxist-Leninist method leads inevitably, unintentionally, to mistakes of a reformist tendency. . . .

My book is methodologically incorrect in divorcing the analysis of economics from politics".

(Evgeny Varga (1949): ibid.; p. 4, 8).

In particular, admitted Varga, this incorrect methodology led to his incorrect characterisation of the state under monopoly capitalism as, in 'normal' times, the machinery of rule of the capitalist class as a whole, and not as the machinery of rule of monopoly capital:

"There is no doubt that I was in error in characterising the modern state as 'an organisation of the bourgeoisie as a whole' rather than, as it should be characterised, as a state of the financial oligarchy".

(Evgeny Varga (1949): ibid.; p. 4-5).

It was this failure to make clear:

�. . . the consolidation of the union of the state apparatus with the financial oligarchy during the war",

(Evgeny Varga (1949): ibid.; p. 5).

declared Varga, which had led him to suggest that the proletariat could gradually increase its influence in the state apparatus until the point was reached where it had the decisive role in the state. Quoting from his book, Varga admitted:

"These lines would win the applause of any reformist, . . .

The question of state power is a question of the correlation of class forces, and can be resolved only in class struggle".

(Evgeny Varga (1949): ibid.; p. 5).

Varga also now accepted that the characterisation he gave in his book of the nature of nationalisation in modern capitalist countries was erroneous:

"The incorrect characterization which I gave of nationalisation in England follows these same lines.

It goes without saying that nationalisation of the important branches of the economy represents a further consolidation of state capitalism. . . .

In view of the class character of the state, nationalisation in England does not signify progress in the direction of democracy of a new type".

(Evgeny Varga (1949): ibid.; p. 6, 7).

A similar fundamental error, admitted Varga, led to

�. . the incorrect evaluation of the changes in relations between England and India. . . .

Was India really transformed into the creditor of England?

In amount of capital, India is England's creditor, but in income from capital England is even now the exploiter of India.�

(Evgeny Varga (1949): ibid.; p. 7).

Varga confirmed his earlier admission of error in characterising the People's Democracies of Eastern Europe both as 'state capitalist' and now also as of 'relatively small' significance:

"The break-off of these countries (the People's Democracies � Ed.) from the imperialist system was undoubtedly one of the most important social-economic results: of the second world war and signifies a deepening of the general crisis of capitalism. . . .

It was incorrect to assert . . . that state capitalism predominates in these countries. It was especially incorrect to evaluate their

Significance... as 'relatively small".

(Evgeny Varga (1949): ibid.; p. 8, 9).

He now also accepted that he had been in error in asserting that genuine state economic planning could occur in modern capitalist countries:

"I made these mistakes worse by the assertion that since the war 'something in the way of a unique "state plan" has appeared in certain capitalist countries'. I must admit that all my assertions concerning the question of 'planning under capitalism' are a great retreat from my correct position in 1935

A still more resolute struggle must be carried on against the mendacious propaganda conducted by the reformists for a planned economy under capitalism".

(Evgeny Varga (1949); ibid.; p. 8).

Finally, Varga agreed that he had been seriously in error in paying little intention to the intensification of the general crisis of capitalism:

"The fact that the book did not take up the question of the deepening of the general crisis of capitalism has tremendous importance. This inevitably causes the reader to imagine that the world war did not reflect the deepening of the crisis. . . . The absence of problems

concerning the general crisis of capitalism is a serious omission.

(Evgeny Varga (1949): ibid.; p. 9).

Thus, Varga had now admitted that all the theses for which he had been criticised were erroneous, except his allegation that wars were no longer inevitable under imperialism.

He now announced that he had abandoned as unsound his original plan to write a second volume of his work dealing with political questions:

"I must draw lessons for the future from the mistakes made. My plan to deal with political problems as a . . . second volume to my work is now out of the question. .

In short, instead of the planned second volume of my former work, a new, independent book must be written on the economic and political post-war problems of imperialism, without the reformist mistakes I made in the book".

(Evgeny Varga (1949); ibid.; p. 9).

The Reduction in Stalin's Authority (1929-52)

Over the years, Stalin and the Marxist-Leninists in leading positions in the CPSU were engaged in a continuing struggle against spurious 'Marxist-Leninists' -- revisionists:

"The source of this 'frame of mind', the soil on which it has arisen in the Party, is the growth of bourgeois influence on the Party, in the conditions of . . . the desperate struggle between the capitalist and socialist elements in our national economy. The capitalist elements are

fighting not only in the economic sphere; they are trying to carry the fight into the sphere of proletarian ideology,

and it cannot be said that their efforts have been entirely fruitless, .

There can scarcely be any doubt that the pressure of the capitalist states on our state is enormous, that the people who are handling our

foreign policy do net always succeed in resisting this pressure, that the danger of complications often gives rise to the temptation to take the path of least resistance, the path of nationalism".

(Josef V. Stalin: 'Questions and Answers' (June 1925), in: 'Works', Volume 7; Moscow; 1954; p. 166-67, 171).

and Stalin took his stand firmly on the side of Marxism-Leninism:

"Either we continue to pursue a revolutionary policy, rallying the proletarians and the oppressed of all countries around the working class of the USSR � in which case international capital will do everything it can to hinder our advance;

Or we renounce our revolutionary policy and agree to make a number of fundamental concessions to international capital -- in which case international capital, no doubt, will not be averse to 'assisting' us in converting our socialist country into a 'good' bourgeois country".

(Josef V. Stalin: Report at a Meeting of the Active of the Moscow Organisation of the CPSU (April 1928), in: 'Works', Volume 11; Moscow; 1954; p. 58-59).

Over the years, the still concealed revisionists in leading positions in the CPSU were able, slowly but steadily, to reduce the influence of Stalin --now by far the most astute and politically advanced Marxist-Leninist in the leadership.

Until 1927, Stalin made numerous contributions to the work of the Communist International; after 1927 -- nothing. To disguise the significance of this enforced withdrawal, the false story was spread that

�. . . Stalin did not share Lenin's commitment to the idea of the Communist International"

(Robert H. McNeal: 'Stalin: Man and Ruler'; Basingstoke; 1988; p. 218).

In 1949 publication in the Soviet Union of Stalin's 'Sochineniya' (Works) was halted at Volume 13, covering the period 1930-1934.

This limitation of Stalin's influence was concealed to some extent by the 'cult of personality' which the revisionist conspirators built up around Stalin. Nevertheless it was noted by the most astute analysts, such as the American William McCagg, Junior*:

"In 1950 and 1951 Stalin's power was limited".

(William 0. McCagg, Junior: 'Stalin Embattled: 1943-1948'; New York; 1975; p. 307).

until he became virtually what McCagg calls 'the prisoner in the Kremlin':

"The reports from the (US -- Ed.) Moscow Embassy strongly fostered the 'prisoner' image of Stalin at this time".

(William O. McCagg, Junior: ibid.; p. 382).

In October 1952, the revisionists succeeded in demoting Stalin from the post of General Secretary of the Central Committee of the CPSU -- a post he had held since April 1922 -- to that of one of several Secretaries:

"After the 11th Party Congress, on April 3, 1922 the Plenum of the Central Committee, on V. I. Lenin's motion, elected Stalin as Secretary-

General of the Party; Stalin served in this post until October 1952, and from then until the end of his life he was Secretary of the Central Committee".

('Entaiklopedichesky slovar' (Encyclopaedic Dictionary), Volume 3; Moscow; 1955; p. 310).

"Stalin ceased to be General Secretary of the Central Committee. . .

. He had lost all those special powers which went with the position and which set him apart from the other members of the Central Committee Secretariat".

(Boris Nikolaevsky: 'Power and the Soviet Elite'; New York; 1965; p. 92).

Stalin's 'Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR' (1952)

Stalin was prevented from playing a leading role at the 19th Congress of the CPSU, which opened on 5 October 1952:

"In a break with a long tradition going back to the twenties, it was not Stalin who presented the Central Committee report, nor did he take part in the deliberations".

(Gabor T. Ritterspoorn: 'Stalinist Simplification and Soviet Complications: Social Tensions and Political Conflicts in the USSR: 1933-1553'; Reading; 1991; p. 219).

"Stalin himself sat at a separate tribune during the proceedings and said nothing, apart from the brief concluding speech". (Robert H. McNeal: op. cit.; p. 299).

"Stalin sat in total isolation. . He appeared at the congress

only at the opening and closing sessions".

(Dmitri Volkgoonov: 'Stalin: Triumph and Tragedy'; London; 1991; p. 568).

In spite of this,

. the star role, and the only important one, was played by Stalin and . . . it was played not at the Congress, but before it opened. .

This Stalin achieved by issuing, a few days before the delegates met in Moscow, a new 'master work'. . . . It completely stole the thunder of the Congress, as it was obviously intended to do".

(Harrison Salisbury: 'Stalin's Russia and after'; London; 1955; p. 148).

"'Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR' was given to the world on October 3 and 4, filling two entire issues of 'Pravda'. And on October S the 19th Congress of the CPSU opened"

(Adam B. Ulam: 'Stalin: The Man and His Era'; London; 1989; p. 731),

The essence of the work was that it

. strongly attacked pro-capitalist tendencies in the USSR".

(Kenneth'W. Cameron: 'Stalin: Man of Contradiction'; Toronto; 1987; p. 118).

and the success of Stalin's tactics is shown by

�. . the decision of the 19th Party Congress to base the new Party programme on Stalin's 'Economic Problems".

(Abdurahman Avtorkhanov: 'Stalin and the Soviet Communist Party: A Study in the Technology of Power'; London; 1959; p. 249).

Here we shall note only one aspect of this anti-revisionist content of the work -- namely, the section on the continuing validity of Lenin's thesis on the inevitability of war under imperialism.

"Some comrades hold that, owing to the development of new international conditions since the Second World War, wars between

capitalist countries have ceased to be inevitable. . . .

These comrades are mistaken. . . .

It is said that Lenin's thesis that imperialism inevitably generates war must now be regarded as obsolete, since powerful popular forces have come forward today, in defence of peace and against another world war. That is not true.

The object of the present-day peace movement . . . is not to overthrow capitalism and establish socialism. It confines itself to the democratic aim of preserving peace. . . .

It is possible that in a definite conjuncture of circumstances the fight far peace will develop here or there into a fight for socialism. But then it will no longer be the present-day peace movement; it will be a movement for the overthrow of capitalism.

What is most likely is that the present-day peace movement will, if it succeeds, result in preventing a particular war, in the temporary preservation of a particular peace. in the resignation of bellicose government and its supersession by another that is prepared temporarily to keep the peace. That, of course, will be good. Even very good. But, all the same, it will not be enough to eliminate the inevitability of wars between capitalist countries generally. It will not be enough because, for all the successes of the peace movement, imperialism will remain -- and, consequently, the inevitability of wars will also continue in force.

To eliminate the inevitability of war, it is necessary to abolish imperialism".

(Josef V. Stalin: 'Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR' (February-September 1952), in: 'Works', Volume 16; London; 1986; p. 327, 331,332).

Varga's New Self-Criticism (1952)

It will be recalled that, prior to 1952, Varga had admitted the correctness of all the criticisms levelled at his book 'Changes in the Economy of Capitalism as a Result of the Second World War' except that to the effect that war was 'no longer inevitable' under imperialism":

The passage in Stalin's 'Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR' relating to this question

�. . . was clearly directed against Varga".

(Philp J. .Jaffe: op. cit.; p. 121).

Following the publication of Stalin's work, Varga felt it necessary to issue a further self-criticism admitting that he was 'in error' on this question also.

His declaration was made at an augmented meeting of the Learned Council of the Economics Institute of the USSR Academy of Sciences in November 1952.

The official report of the meeting states:

"Academician Varga was the first to take the floor. . . . We workers of the Economics Institute, he said, from post-graduate students up to Academicians, express a feeling of profound appreciation to Comrade Stalin for his new classic, for the huge contribution which he has made to Marxist-Leninist economics and for the invaluable aid he has rendered all economists. A profound study of Comrade Stalin's brilliant work will help each of us to improve his work. The basic economic law of modern-day capitalism, which Comrade Stalin revealed, will give us a key to the understanding and clarification of the present-day status of imperialism and a perspective on it further development. This law defines all the main features of monopoly capitalism. . . .

Academician Varga acknowledged that he had been mistaken in supposing that the Leninist thesis of the inevitability of wars among capitalist countries had become obsolete in present-day conditions. . . .

I acknowledge that I was mistaken in this question, said Academician Varga. Comrade Stalin gave a thorough demonstration of the inevitability of wars among capitalist countries even at the present stage. I consider that if, in the course of our work, we have committed a mistake, we are obliged honourably to acknowledge it and not to repeat it".

('Tasks of the Economics Institute of the USSR Academy of Sciences in Connection with Publication of J. V. Stalin's Brilliant Work 'Economic Problems et Socialism in the USSR', in: 'Current Digest of the Soviet Press', Volume 5, No. 3 (26 February 1953); p. 6).

Varga's 'Rehabilitation' (1954)

After the death of Stalin in 1953 and the subsequent accession to power of the new revisionist leadership of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, headed by Khrushchev, Varga was 'rehabilitated' and in 1954 awarded the Order of Lenin:

"Under Khrushchev, . he (Varga -- Ed.) was not only rehabilitated, but received the Order of Lenin in 1954".

(Philip J. Jaffe: op. cit,.; p. 123).

And in 1963 --- the year before his death -- Varga was awarded

" . . . the Lenin Prize for distinguished contributions to the development of Marxist-Leninist science'.

('Great Soviet Encyclopedia', Volume 4; New York; 1974; p. 509).

Varga's 'Politico-Economic Problems of Capitalism' (1964)

That Varga's 'self-criticism' was not sincere was established in 1964, when he published a new book entitled 'Ocherki po problemam politekonomy kapitalizma' (Essays on Politico-Economic Problems of Capitalism). An English translation appeared in 1968, after his death, under the title 'Politico-Economic Problems of Capitalism'.

Varga presented the book as a polemic against 'the distortion of economic science in the time of Stalin', saying:

"The book, written polemically, is directed against thoughtless dogmatism, which until recently was widespread in works on the economy and politics of capitalism".

(Evgeny Varga: 'Politico-Economic Problems of Capitalism'; Moscow; 1968 (hereafter listed as 'Evgeny Varga (1968)); p. 11).

He admitted that his earlier 'self-criticisms' had not been made as a result of pressure within the Soviet Union, placing the blame upon the foreign press:

"At the time of the debate, I was compelled to put an end to the discussion by admitting that there were mistakes in my book. This was not because pressure was exerted on me in the Soviet Union, but because the capitalist press, and especially the American papers, . . . used it for violent anti-Soviet propaganda, asserting that I was pro-West, was opposing the Communist Party, etc. It therefore became a matter of little importance to me whether my critics or I were right. . . . The bourgeois press was trying to make the capitalist world see me as an opponent of my own Party, and this was something that I could not tolerate".

(Evgeny Varga (1968): op. cit.; p. 50).

However, he now repeated almost all the statements which he had earlier admitted to have been 'incorrect'.

He now repeated:

1) his claim that the modern capitalist state was the machinery of rule of monopoly capital only in 'normal' conditions, while in conditions

of emergency, such as war it became the machinery of rule of the capitalist class as a whole:

"Under 'normal' conditions. i. e., when the capitalist social system is not subjected to any immediate danger, the monopoly capitalist state is a state of the monopoly bourgeoisie. . . .

The state acts on behalf of the interests of the whole bourgeoisie at times when the existence of the capitalist social system is in direct

danger. . . .

The objection was that 'it is not the state but the monopolists who are the decisive force in the war economy'. This objection is a simple logical mistake. . . . Monopoly capital assumes a decisive role only with the introduction of a war economy. . . .

Stalin's conception ('state-monopoly capitalism implies the subordination of the state apparatus to the capitalist monopolies') is wrong".

(Evgeny Varga (1968): op. cit.; p. 45-46, 47, 55).

2) his claim that under modern capitalism state economic planning was possible:

"Let us turn to the problem of economic planning by the capitalist state. . . .

Even now in times of peace, a number of bourgeois states have adopted 'five-year plans'. India, for example, is now implementing its third five-year plan. . . .

It cannot 'be denied that the six Common Market- countries have 'planned' their economic policy for a period of twelve years in advance.

. The European Coal and Steel Community also operates according to plan".

(Evgeny Varga (1968): op. cit.; p. 48, 49).

3) his claim that wars are no longer inevitable under imperialism:

"There are dogmatists today who reiterate that inter-imperialist wars are unavoidable even today. But they are wrong, because they disregard the profound changes that have taken place in the world since the time when this theory was formulated. . . .

The historic events of the past twelve years have refuted the conception on which Stalin built his theory on the inevitability of inter-imperialist wars. His conception was based on the view that economically the USA will always have the edge over Britain, France, West Germany and Japan".

(Evgeny Varga (1968): op. cit.; p. 75, 79).

Here Varga sinks down to gross distortion. To 'have the edge over' means

" . . . have . . . an advantage over".

('Oxford English Dictionary', Volume 5; Oxford; 1989; p. 67).

But Stalin does not state that the USA will always have the advantage over the imperialist powers of Europe and Asia. He says:

"Would it not be truer to say that capitalist Britain and, after her, capitalist France, will be compelled in the end to break from the embrace of the USA and enter into conflict with it in order to secure an independent ..position and, of course, high profits?".

(Josef V. Stalin (1952): op. cit.; p. 328).

In spite of Varga's declaration in 1952 that Stalin's 'Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR' was a 'brilliant work', by 1964 he was denouncing key parts.

For example, Stalin insisted that, as a result of the Second World War, the

". .. people's democracies broke away from the capitalist system. �..

. The economic consequences of the existence of two opposite camps was that the single all-embracing world market disintegrated. . . .

It follows from this that the sphere of exploitation of the world's resources by the major capitalist countries (USA, Britain, France) will not expand, but contract".

(Josef V. Stalin (1952): op. cit.; p. 324, 326).

Varga now denounced this analysis as 'unfounded' and 'wrong':

"Stalin's unfounded assertion about the narrowing of the capitalist market over the years to come is to this day still echoed by some Soviet economists. . . .

Stalin was wrong when he predicted a shrinking of the capitalist market".

(Evgeny Varga (1968): op. cit.; p. 164, 174).

Of course, It is true that, as a result of the betrayal of socialism by the revisionists, this process of contraction of the capitalist world market was later reversed. But this occurred only after 1953, and does not invalidate the analysis made by Stalin in 1952.

Even Stalin's 'basic economic law of modern capitalism' � described by Varga in 1952 as 'a key to the understanding and clarification of the present-day status of imperialism' -- had by 1964 become, in Varga's view, 'unfounded':

"Stalin's assertion that 'it is not the average profit but the maximum profit�, that modern monopoly capitalism needs, . . . is entirely unfounded"

(Evgeny Varga (1968): op. cit.; p. 162).

Varga argues that

�. the striving for maximum profits is not distinctive of modern capital".

(Evgeny Varga (1968): op. cit.; p. 163).

It is, of course, true that all capitalists, and not only monopoly capitalists, strive for maximum profit. But Stalin's law does not speak of striving for, but of securing, maximum profit:

"The main features and requirements of the basic economic law of modern capitalism ,-might be formulated roughly in this way: the securing of the maximum capitalist profit".

(Josef V. Stalin: (1952): op. cit.; p. 334).

In conditions of capitalist competition, the rate of profit is, in the long run, limited to the average rate:

"Competition levels the rates of profit of the different spheres of production into an average rate of profit".

(Karl Marx: 'Capital: A Critique of Political Economy', Volume 3; London; 1974; p. 208).

This is because, where capitalist competition exists, if capitalists in one sphere of production are making a rate of profit above the average, capitalists in other spheres rush to invest in that sphere, so causing prices and the rate of profit to fall until the rate of profit in that sphere has fallen to the average level. Conversely, if capitalists in one sphere of production are making a rate of profit below the average, capitalists rush to transfer their capital to other, more profitable, spheres, so causing prices and the rate of profit to rise until the rate of profit has risen to the average level.

Consequently, under conditions of competition, capitalists strive to obtain the maximum rate of profit, but cannot in the long run succeed in

obtaining it.

But Stalin is dealing in 'Economic Problems of Socialism, in the USSR' with modern capitalism, which is monopoly capitalism, where effective competition no longer exists. Thus, in modern capitalism, capitalists may not merely strive for maximum profit, they may secure it. Hence, Stalin states

correctly that ---'-‑

" . . . the main features and requirements of the basic economic law of modern capitalism might be formulated roughly in this way: the securing of the maximum capitalist profit".

(Josef V. Stalin (1952): op. cit.; p. 334).

It is clear that by the term 'maximum profit', Stalin meant the maximum possible profit in conditions of monopoly. Yet in an effort to to present Stalin s basic economic law of modern capitalism as 'sheer nonsense', Varga pretends to understand Stalin's term as the maximum imaginable profit for monopoly capital, namely as that profit which would accrue to monopoly capital if it appropriated all the profit being made in society:

"The term 'maximum profit' was intended to express that monopoly capital appropriates all the surplus value being created in capitalist society. This is sheer nonsense".

(Evgeny Varga (1968): op. cit.; p. 163).

Varga's 'Testament' (1964)

Shortly before his death, Varga wrote

�. . a political statement titled 'The Russian Way and its Results', . . . . known since as Varga's 'Testament".

(Philip J. Jaffe: op. cit.; p. 130).

The document was

" . circulated in typewritten copies by the underground press in the Soviet Union (Samizdat) but never officially published".

(Philip J. Jaffe: op. cit.; p. 130).

According to Varga's 'Testament', negative features in Soviet life dated from the period when Stalin was Secretary-General of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union:

"All these negative features stem from the period of the Stalinist leadership, which lasted about 30 years".

(Evgeny Varga 'Political Testament', in: 'New Left Review', No. 62; (July-August 1970) (hereafter listed as "Evgeny Varga (1970)'); p. 42). .

According to Varga, under Stalin's leadership the dictatorship of the proletariat degenerated into the 'dictatorship of the top group of the Party bureaucracy':

"The dictatorship of the proletariat, whose theoretical foundations were laid by Marx and Lenin, rapidly became a dictatorship of the top group of the Party bureaucracy. . . .

This produced a total degeneration of the 'power of the Soviets".

(Evgeny Varga (1970): op. cit.; p. 36, 37).

which existed only in name:

"'Soviet power' exists . . . in our country only in the sense that the Party leaders govern the country in the name of the Soviets".

(Evgeny Varga (1970): op. cit.; p. 38).

Stalin built up, according to Varga, a system of repression directed against both opponents and colleagues until the Soviet Union became only quantitatively different from Nazi Germany:

"In 1934, when Stalin started to destroy his most prominent opponents within the Party, he simultaneously eliminated some of his own entourage

who opposed his rise and his methods of leadership. . . .

To justify this mass repression exercised against ordinary citizens, Stalin constructed a special theory according to which the class struggle in a country building socialism would be continued and even intensified for a long period, until u new society was built and consolidated. . . .

Although there were fewer torturers and sadists in the prisons and concentration camps of Stalin than in those of Hitler, one can say that there was no difference in principle between them".

(Evgeny Varga (1970): op. cit.; p. 38, 39).

Varga alleges that Party leadership in the time of Stalin 'ruined co-operative agriculture':

"The Stalinist leadership ruined the collective farms . . . and produced a kolkhoz peasantry which had no interest in its own work".

(Evgeny Varga (1970): op. cit.; p. 34).

Varga thus presents the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, in the time of Stalin, as an all-powerful 'bureaucratic oligarchy', which despised the working people:

"This bureaucratic oligarchy of the Party controls all the 'levers' of the Party apparatus and the government. . . .

Thu members of the 'nomenclature' were . . . given an institutionalised position of privilege over the toiling masses. The bureaucratic oligarchy of the Party thus freed itself from the public opinion of the workers and became accustomed to despising them".

(Evgeny Varga (1970): op. cit.; p. 32).

being in fact 'an instrument for their exploitation':

"In industry, the state directly appropriated surplus value. . . .

The centralised Party-bureaucratic state . . . appropriates the surplus value created by the labour of the working population and uses it for its own needs. . .

The officials of the 'nomenclatura' and their families . . . appropriate a certain part of the surplus --- value created by the labour of manual workers, collective farmers and office employees. . . .

The unlimited power of the bureaucratic leadership of the Party conceals from the workers the mechanism of the ferocious economic exploitation of the workers, employees and -- most of all -- the peasants of the collective farms".

(Evgeny Varga (1970): op. cit.; p. 33, 35, 36).

What, no doubt, made Varga's anti-Stalin diatribe unacceptable to the new Soviet revisionist leadership was his allegation that under their 'reforms' nothing had fundamentally altered, and that real change required a new top leadership:

"After Stalin's death in 1953, it seemed that remarkable changes were taking place in Soviet society. . . .

But . . . was the structure of society really changed? This question must be answered in the negative. . . .

To change the existing situation in the country, a radical change in the top leadership is necessary. To expect an initiative from below is impossible".

(Evgeny Varga (1970): op. cit.; p. 42, 43).

Leon Trotsky, despite his fierce attacks on the Soviet Union in the time of Stalin, maintained until his death that it remained a workers' stare, even though 'distorted':.

"The attempt to represent the Soviet bureaucracy as a class of 'state capitalists' will obviously not withstand criticism".

(Leon Trotsky: 'The Revolution Betrayed: What is the Soviet Union and where is it going?'; New York; 1937; p. 249).

Some Trotskyist groups, however, maintain that the Soviet Union in the time of Stalin was a society where the 'Stalinist bureaucracy' constituted 'a ruling, exploiting class of state capitalists':

"The Stalinist bureaucracy qualifies as a class. . . .

The Russian bureaucracy .. . is the personification of capital in its purest form. . . .

The workers . . . are politically expropriated, they are also economically exploited. The rate of exploitation, that is, the ratio

between surplus value and wages, does not depend on the arbitrary will of the Stalinist government, but is dictated by world capitalism".

(Tony Cliff: 'State Capitalism in Russia'; London; 1974; p. 166, 169, 180, 209).

CLEARLY, AT THE END OF HIS LIFE VARGA CAME EXTREMELY CLOSE TO THE TROTSKYISM HE HAD OPENLY ESPOUSED IN THE 1920s.

The Revisionists' Obituary of Varga (1964)

Varga died on 8 October 1964. His glowing obituary, published in 'Pravda' on 9 October, was signed by Nikita Khrushchev*, Anastas Mikoyan* and other revisionist leaders. It described him as:

�. . . an outstanding representative of Marxist-Leninist economic science. . . .

The works of E.S. Varga are imbued with party-spirit, and irreconcilability with any manifestation of the dogmatism or revisionism, vulgarisation or doctrinairism which called themselves science in the years of the cult of personality".

(Obituary of Evgeny Varga, in: 'Pravda' , 9 October 1964, in: Evgeny Varga (1970): op. cit.; p. 30).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

AVTORKHANOV, Abdurahman: 'Stalin and the Soviet Communist Party: A Study in the Technology of Power'; London; 1959.

BARGHOORN, Frederick J.: 'The Varga Discussion and its Significance', in:

'American Slavic and East European Review', Volume 7 (October 1946). CAMERON, Kenneth W.: 'Stalin: Man of Contradiction'; Toronto; 1987. CLIFF, Tony: 'State Capitalism in Russia; London; 1974.

DEUTSCHER, Isaac: 'The Prophet Outcast: Trotsky: 1929-1940'; London; 1970. DOMAR, Evsey D.: 'The Varga Controversy', in: 'American Economic Review', Volume 40, No. 1 (March 1950).

JAFFE, Philip J.: 'The Rise and Fall of American Communism'; New York; 1975. LASH, Joseph P.: 'Iron Curtain for the Mind', in: 'New Republic', Volume 109, No. 126 (27 December 1948).

LAZITCH, Branko & DRACHKOVICH, Milorad M.: 'Biographical Dictionary of the Comintern'; Stanford (USA); 1973.

LONGSWORD, John: 'The Varga Business', in: 'Spectator', No. 6,320 (12 August 1949).

MARX, Karl: 'Capital: A Critique of Political Economy', Volume 3; London; 1974.

McCAGG, William 0., Junior: 'Stalin Embattled: 1943-1948'; New York; 1975. McNEAL, Robert H.: 'Stalin: Man and Ruler'; Basingstoke; 1988.

NIKOLAEVSKY, Boris: 'Power and the Soviet Elite'; New York; 1965.

RITTERSPOORN, Gabor T.: 'Stalinist Simplification and Soviet Complications: Social Tensions and Political Conflicts in the USSR: 1933-1953'; Reading; 1991.

R. S.: 'The Discussions on Varga's Book on Changes in Capitalist War Economy'. in: 'Soviet Studies', Volume 1, No. 1. (June 1949).

SALISBURY, Harrison: 'Stalin's Russia and after'; London; 1955.

STALIN, Josef V.: 'Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR', in: 'Works', Volume 16; London; 1986.

TROTSKY, Leon: 'The Revolution Betrayed: What is the Soviet Union and where is it going?'; New York; 1937.

--- : 'The Trotsky Archives', in Harvard University.

ULAM, Adam B.: 'Stalin: The Man and his Era'; London; 1989.

VARGA, Evgeny: 'Izmeniya v Ekonomike Kapitalizma v Itoge Vtoroi Mirovoi Voiny'; Moscow; 1946.

: 'Politico-Economic Problems of Capitalism'; Moscow; 1968.

--- 'Political Testament', in: 'New Left Review', July-August

1970.

VOLKOGONOV, Dimitri: 'Stalin: Triumph and Tragedy'; London; 1991.

ZAUBERMAN, Alfred: 'Economic Thought in the Soviet Union', in: 'Review of Economic Studies', Volume 16, No. 41 (1949-50).

'Soviet Views on the Post-war World Economy: An Ofiicial Critique of Evgeny Varga's 'Changes in the Economy of Capitalism Resulting from the Second World War'; Washington; 1948,

'Current Digest of the Soviet Press'.

'Entsiklopedichesky slovar', Volume 3; Moscow; 1955. 'Fortune', Volume 37 (March 1948).

'Oxford English Dictionary', Volume 5; Oxford; 1985. 'Great Soviet Encylopedia', Volume 4; New York; 1970. 'Keesing's Contemporary Archives'.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES IN ALLIANCE 17 � Varga and Vosnosensky

ABAKUMOV, Viktor S., Soviet Marxist-Leninist politician (1894-1964); USSR. Minister of State Security (1950-51); judicially murdered by revisionists (1954).

BERIA, Lavrenty P., Georgian-born Soviet Marxist-Leninist politician; 1st, Party Secretary, Georgia (1931-38); USSR Commissar of Internal Affairs (1938-45); member, State Defence Committee (1941-55); USSR Premier (1941); marshal (1945); USSR Deputy Premier (1953); judicially murdered by revisionists (1953).

BIRON, Ernst J., German-born Russian adventurer (1690-1772); became lover of Russian Empress Anna Ivanovna (1727); to Russia as her grand chamberlain (1730); count (1730); regent of Russia (1740); arrested and deported (1740).

CONQUEST, G. R. Robert A., British diplomat, poet and historian (1917- ); research fellow, London School of Economics (1956-58); literary

editor, 'Spectator' (1962-63); senior fellow, Columbia University, New York (1964-65); fellow, Woodrow Wilson International Centre, Washington (1976-77); research fellow , Hoover Institute, Stanford. (1977-79, 1981‑

)

DEDIJER, Vladimir, Yugoslav revisionist politician (1914-90); director of information (1949-50); Professor of Modern History, University of Belgrade (1954-55); expelled from LCY (1954); fellow, St. Anthony's College, Oxford (1962-63); research associate, Harvard University, (1963-64).

DJILAS, Milovan, Yugoslav revisionist politician (1911- ); member, Politburo. CPY (1940-54); vice-president (1953-54); removed from all posts (1954); resigned from Party (1954); imprisoned (1956-61, 1962-66).

DUHRING, K. Eugen, German idealist philosopher and economist (1833-1921).

FEDOSEYEV, Petr N., Soviet revisionist philosopher (1908- ); researcher, Institute of Philosophy (1936-41); Chief Editor, 'Bolshevik' (1941-49); Chief Editor, 'Party Life' (1954-55); Director, Institute of Philosophy (1955-62); Academician (1960); Vice-President, USSR Academy of Sciences (1962-67, 1971-86)); Director, Institute of Marxism-Leninism (1967-71).

KAGANOVICH, Lazar M., Soviet Marxist-Leninist politician (1893-1991); Secretary, CP, Ukraine (1925-28); Secretary, CC., RCP (1928-30); Party Secretary, Moscow (1930-35); USSR Commissar of Transport (1935-37, 1939-40); USSR Commissar of Heavy Industry (1937-38); USSR Commissar of Fuel Industry (1939-41); Member, State Defence Committee (1942-43); Minister of Building Materials Industry (1946); Party Secretary, Ukraine (1947); USSR Deputy Premier (1947-52); expelled from Party (1962); manager, Sverdlovsk Cement Plant (1957-63).

KAPUSTIN, Yakov F., Soviet revisionist politician (1904-50); 2nd Party Secretary, Leningrad (1945-49); found guilty of treason and executed (1950).

KARDELJ, Edvard , Yugoslav revisionist politician (1910-79); Deputy Premier (1945-53); Minister of Foreign Affairs (1948-53); President, Federal Assembly (1963-67).

KOSYGIN, Aleksey N., Soviet revisionist politician (1904-80); Mayor, Leningrad (1938-39); USSR Commissar of Textile Industry (1939-40); USSR Deputy Premier (1940-43); USSR Minister of Light Industry (1948-53); Member, Politburo, CC, CPSU (1948-52, 1960-80); USSR Minister of Industrial Consumer Goods (1953-54); USSR Deputy Premier (1953-64); USSR Premier (1964-80)

KUZNETSOV, Aleksey A., Soviet revisionist politician (1905-50); major-general (1943); 1st Party Secretary, Leningrad (1945-49); Secretary, CC (1946-50); found guilty of treason and executed (1950).

LAZUTIN, Pytor G., Soviet revisionist politician (1905-50); Party Secretary, Leningrad (1941-43); Deputy Party Secretary, Leningrad (1943-44); Deputy

Mayor, Leningrad (1944-46); Mayor, Leningrad (1946-49); found guilty of treason and executed (1951):

LEONHARD, Wolfgang, Austrian-born American historian (1921- ); radio

presenter, Radio Moscow (1943-45); adviser to Communist Party of Germany Socialiist Unity Party (1945-47); teacher, Karl Marx Party High School, German Democratic Republic (1947-49); senior research fellow, Columbia

University, New York (1963- 64); professor of history, Yale

University, New Haven (1966-87).

MALENKOV, Georgi M., Soviet Marxist-Leninist politician (1901-88); Member, State Defence Committee (1941-45); USSR Deputy Premier (1946-53); USSR Premier (1953-55); USSR Minister of Power Stations (1955-57); retired (1968),

MEEK, Ronald M., New Zealand-born economist (1917-78); lecturer in (1948-61), senior lecturer in (1961-63), professor of, economics, University of Leicester (1963-78).

McCAGG, William 0., Junior. American historian (1930- ); assistant professor of history, Fairleigh Dick University, Rutherford (1962-64); assistant professor (1964-71), associate professor (1971-77), professor,

of history, Michigan State University , East Lancing (1977- ).

McFARLANE, Bruce J., Australian economist (1936- ); senior lecturer, economic policy, Australian National University, Canberra (1963-72); reader in (1972-70), professor of, politics, University of Adelaide (1976- ).

MIKOYAN, Anastas, Armenian-born Soviet revisionist politician (1895-1978); USSR Commissar of Trade (1926-30); USSR Commissar of Supply (1930-34); USSR Commissar of Food Industry (1934-38); USSR Deputy Premier (1937-46), 1955-64); USSR Minister of Trade (1946-53); USSR President (1964-65).

MOLOTOV, Vyacheslav M., Soviet Marxist-Leninist politician (1890-1986); member, Political Bureau/Presidium, CP (1926-52); USSR Premier (1930-41); USSR Deputy Premier (1941-57); member, State Defence Committee (1941-45); USSR Commissar/Minister of Foreign Affairs (1939-49, 1953-56); USSR Minister of State Control (1956-57); USSR Ambassador to Mongolia (1957-60); Soviet rep. on International Atomic Agency (1960-62); expelled from Party (1964); reinstated in Party (1984).

POPKOV, Pyotr S., Soviet revisionist politician (1903-50); Mayor, Leningrad (1939-46); 1st. Party Secretary, Leningrad (1946-49); found guilty of treason and executed (1951).

RODIONOV, Milhail I., Soviet revisionist politician (1907-50); Premier, RSFSR (1946-49); arrested (1949); found guilty of treason and executed (1950).

SHEPILOV, Dmitri T., Soviet revisionist politician (1905- ); Director, Agitation and Propaganda Dept., CC, CPSU (1948-52); Chief Editor, 'Pravda' (1953-56); Secretary, CC (1955-56, 1957); Minister of Foreign Affairs (1956-57).

SUSLOV, Milkhail A., Soviet revisionist politician (1908-82); Secretary, CC (1947-52); Director, Dept. of Agitation and Propaganda, CC, CPSU (1946-82); chief Soviet delegate to Cominform (1948-53); Chief Editor, 'Pravda' (1949-50); Member, Politburo, CC, CPSU (1952, 1955-82).

VOZNESENSKY, Aleksandr A., Soviet revisionist politician (1900-50); Rector, University of Leningrad (1944-48); Minister of Education, RSFSR (1946-49); found guilty of treason and executed (1950).

VOZNESENSKY, Nikolay A., Soviet revisionist economist {1903-51); Chairman, USSR State Planning Committee (1938-49); USSR Deputy Premier (1941-49); Academician (1943); Member, Politburo, CC, CPSU (1947-49); found guilty of treason and executed (1951).

WILES, Peter J. D. F., British economist (1919- ); professor of economics, Brandeis University, Waltham (USA) (1960-63); professor of Russian social and economic studies, London School of Economics (1965- ).

ZHDANOV, Andrey A, Soviet Marxist-Leninist politician (1896-1948); Party Secretary, Leningrad (1934-44); member, State Defence Committee (1941--44); colonel-general (1944); secretary, CC, CPSU (1944-48); murdered by revisionists (1948),

ZINOVIEV, Grigory Y., Soviet revisionist politician (1883-1936); Mayor, Leningrad (1918); President, Communist International (1919-26); expelled from Party (1926); readmitted, and re-expelled (1932, 1934); pleaded guilty to complicity in assassination of Kirov and executed (1936).

GO TO VOSNOSENKSY: Part 2 Alliance 17

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________